• | Deep Impact revisited: As astronomers sift through the data from this week's comet collision, they're starting to answer some of the big questions they had — but are now facing even bigger questions.

For example, when the Impactor probe sent out by the Deep Impact mothership crashed into Comet Tempel 1, the blast threw up a huge cloud of fine powder — stuff that now covers the surface of the nucleus. Those findings are based on observations that were made right after the collision.

"The major surprise was the opacity of the plume the impactor created and the light it gave off," Deep Impact's principal investigator, Michael A'Hearn of the University of Maryland, said in today's mission update. "That suggests the dust excavated from the comet's surface was extremely fine, more like talcum powder than beach sand. And the surface is definitely not what most people think of when they think of comets — an ice cube."

Now scientists are trying to explain how a seemingly solid 3-by-7-mile-wide (5-by-11-kilometer-wide) comet can be made of stuff that's finer than sand.

"You have to think of it in the context of its environment," said Brown University's Pete Schultz, a member of the science team. "This city-sized object is floating around in a vacuum. The only time it gets bothered is when the sun cooks it a little, or someone slams an 820-pound wakeup call at it at 23,000 miles per hour."

The impact created a fireball that expanded at a rate of about 3 miles (5 kilometers) per second, making it difficult to judge just yet how big the resulting crater turned out to be. Scientists are still analyzing the data to come up with a crater size estimate — which is the subject of a Planetary Society contest as well as at least one NASA office pool. But they're pretty sure it's on the high end of expectations, with a width closer to 820 feet (250 meters)than 165 feet (50 meters).

Meanwhile, NBC News space analyst James Oberg reports that the Deep Impact mission sparked grumbling from an Egyptian commentator who insisted that the endeavor has a military rather than a scientific purpose. Even weirder, an online posting on Islamic Community Net claimed that Deep Impact was part of a series of "planetary death weapons tests."

Earlier this week, Cosmic Log correspondent Mark Lyons was among those who said the mission was pretty much a waste of money — but other correspondents quickly leapt to Deep Impact's defense:

Joe Latrell, "Mark Lyons missed the boat entirely on what purpose Deep Impact served. While the money used didn't teach anyone to farm or help drill new wells or go towards AIDS, it did something just as important. It inspired people. While the science is important, the inspiration is doubly so. Right now somewhere in the world a child will make a decision to follow a career in engineering. That decision will lead them down a path that might let them solve some of these problems that Mr. Lyons has brought to our attention. Isn't inspiring children to take a chance and change the world as great a gift as the science learned this week?"Jeff Capron, Modena, N.Y.: "People who think spending on space ventures is a waste should reconsider. If it wasn't for the pioneering done in the past, there would be many millions of people in the Gulf of Mexico and to the south who would probably be dead in a few days. Our satellites are tracking a hurricane in this region now and providing data to all of the countries and areas that will be affected. Had nobody 'wasted' money in pioneering space in the past, think about the costs of a Level 5 hurricane hitting the unknowing masses."Andy Fram, Pompton Lakes, N.J.: "I can understand people's dislike of spending so much money to crash a probe into a comet, especially when the results don't seem to immediately solve any 'relevant,' daily problems. But let us not forget that science learns so much from going through the motions of trying to accomplish this task. Not just from the results of the experiment, but from all the challanges and problems that are experienced along the way. The more scientists learn to overcome challenges and solve problems, the better we are at doing so. Who knows what discoveries can be found along the way and how they may benefit everyone? I know it is expensive, but does anyone really think there will be a time when everyone has enough money and all our everyday issues have been solved so then we can do such experiments?"Chris Eldridge, Harrisburg, Pa.: "As a person who spent almost two decades developing the concept of communal living, I believe that if we really wanted to shelter the homeless and feed the hungry — as Mark Lyons pointed out — we could. The inefficiency of single-family living has created a great 'gap' within our social classes, and until people concern themselves with real solutions that they themselves could implement (as opposed to goverment programs) these problems will never be solved. It is an interesting and grand oportunity we have as such an advanced race. We could easily do all we wanted to — explore space, attempt to cure diseases, and secure our homeland. Identifying wastefulness and streamlining our system to function at its peak is something we should all concern ourselves with."Mark DeChambeau, Washington: "I both agree and disagree with Mark Lyons' comments concerning the importance of the Deep Impact mission — though without the religious overtones. I am not a scientist — in fact, I am a linguist serving in the Armed Forces — so perhaps I don't understand the value gained by knowing the origins of the solar system specifically and the universe in general. I do, however, understand the value of knowledge that can be gained by devoloping and fielding space systems and equipment/techniques to make spaceflight more affordable, economical and routine."The benefits derived from the space program to date have been many and varied from materials technology to propulsion, energy conservation and energy production. I find Mr. Lyons' assertion that the resources used for exploration would be better spent on finding cures to disease, poverty and war to be self-evident but shortsighted. These are serious problems — no one could dispute this — but they are chronic problems related to finite resources and human nature itself. I'm not sure we can solve them with the resources at hand. If we continue to invest in space and space exploration to the point where it becomes profitable, the possibilities may be nearly limitless."In short, I personally feel that any programs which do not fairly directly impact the development of manufacturing and or energy production and that will not contribute at all to getting humanity off this one tiny globe should be seriously screened for their practical value. In short, esoteric, arcane knowledge gained for its own sake may benefit a very few in the short term, but practical experience and development of technology and techniques may benefit all of mankind in the long run. In short, let us focus our efforts!"

• | Final-frontier insurance: There's a mantra about private-sector spaceflight that I've heard over and over from the folks at Oklahoma-based TGV Rockets: "Amateurs talk propulsion, professionals talk insurance." TGV's chief executive officer, Pat Bahn, reminded me of the mantra this week in reference to an Associated Press report on Rocketplane Ltd., another Oklahoma company trying to get into the suborbital space market.

As previously reported, Rocketplane has been negotiating for the use of Rocketdyne engines, but it turns out that Rocketdyne is asking for $100 million to cover its potential liability, just for the ground testing. That's about four times as much as it cost Mojave Aerospace Ventures to create a whole spaceship from the ground up.

“This presents a huge stumbling block,” said David Urie, vice president of Rocketplane.

TGV's chief operating officer, Earl Renaud, said big aerospace players such as Rocketdyne are used to dealing with government agencies that tend to indemnify their suppliers from liability. "They think, 'Whoa, if we don't have that [indemnification], where's the guy with the deep pockets?'" Renaud said.

In the event of a launch accident, lawyers would probably go after the better-capitalized suppliers as well as the rocket-engine buyers. "That's what these prime contractors are very nervous about — being at the tail end of a feeding frenzy," Renaud said.

For its part, TGV Rockets is going through a step-by-step spaceship development program with a hush-hush military customer, and Renaud said the design phase was coming right along. "We had a big review with our primary customer, and it went well," he said.

However, he said the customer was keeping a "tight leash" on the project budget, and TGV was "many millions of dollars away" from completing work.

When it comes to developing suborbital spaceships, money makes the world go round — and that's why the SpaceShipOne effort was so fortunate to have a deep-pocketed, hands-off backer like software billionaire Paul Allen. Renaud only wishes he had such an investor.

"If one of those guys walked in the door and gave us a pile of money, obviously it would have ramifications," he said.

• | A sponge's intelligent design: This week's report about sponges that build elegant glass structures for themselves sparked a tantalizing observation from Mike Angove of Newport, R.I.:

"I haven't seen much on the intelligent design/neo-Darwinism debate for a while. Consider the comment by Science author Joanna Aizenberg from Bell Labs/Lucent Technologies in Murray Hill, N.J. (re: sponges): 'It puzzles me. In my wildest dreams I can’t imagine how these fibers are assembled to make the nearly perfect, highly regular square cells, diagonal supports and surface ridges of the cage.' "Not looking for a 'just so' Darwinian yarn here ... I can hand-wave several into existence if need be ... but just what will it take for committed materialists to allow that there might be more to the biological story? All the ID movement wants is to openly consider the following question: Does this kind of evidence better support purposeful design or random chance assembly?"

Certainly the glass skeletons serve a purpose, just like dams built by beavers, or hives built by bees. In all these cases, the creatures that are better builders have a higher chance of surviving and thriving. I'm in the midst of reading Richard Dawkins' "The Ancestor's Tale," and the sponge skeletons, beaver dams and beehives are what he would call "extended phenotypes" for the organisms. But do they point to a purpose designed into those organisms (or genomes) by an intelligent maker? As a matter of faith (or non-faith) you can say yes or no. But if you're pursuing a scientific inquiry, you can't just shrug your shoulders and say that the sponges make their structures this way merely because God made the sponges that way. Am I wrong?

• | Godspeed: For the next week or so, I'll be down in Florida covering the space shuttle Discovery's launch. If I'm lucky, I'll just barely beat the shuttle crew and Hurricane Dennis to the Sunshine State. You can look forward to on-the-scene reports from me and the rest of the NBC/MSNBC news team in our Return to Flight section, including extra helpings of bloggery on The Peacock Blog and The Daily Nightly.

• | Weekend field trips on the World Wide Web:

• The Guardian: Sample 'The Four Elements'

• 'Nova' on PBS: 'Mars Dead or Alive'

• Science @ NASA: Beware the Mars hoax

• Defense Tech: Cracks in London's Panopticon

• | Lessons from London: In the wake of today's terror attacks in London, risk management expert David Ropeik saw signs of heightened concern and heightened security in America — but very little of the naked fear that followed the 9/11 attacks. And as far as he's concerned, that's a good sign.

"It's actually interesting, in that you would think that with something like this happening in a similar sort of country, not in the Far East or Africa, Americans would think, 'Oh my God, now this could happen to me.' And that 'me' factor usually raises fear," said Ropeik, director of risk communication at the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis in Boston. "But the quotes that I heard from people today suggest that it hasn't raised the fear very much."

Part of the reason may be that Americans are accommodating themselves to the risk factors in a post-9/11 world, he said. Also, mass transit attacks aren't exactly new anymore. "But guess what happens if one bus blows up anywhere in the United States," Ropeik said. "It may just be that the 'me' factor still isn't as strong as it would be if it happened here."

Ropeik, a former contributor to MSNBC.com, is the co-author of a book titled "Risk: A Practical Guide for Deciding What's Really Safe and What's Really Dangerous in the World Around You." He has also trained government employees on how to handle risk perception — in fact, he's traveling to a federal nuclear facility this month for just such a task.

Almost three years ago, Ropeik told me that homeland security officials should be more specific about their warnings, and be more forthcoming about telling people how they should respond to heightened alerts. Today, Ropeik saw a lot to like in the federal government's response:

- The Department of Homeland Security raised the alert status from yellow to orange, but only for specific types of mass-transit systems. "That shows the public that they're not crying wolf, that there's a specific reason for the elevation, even though there wasn't specific intelligence about a threat," Ropeik said.

- Homeland security chief Michael Chertoff asked mass-transit riders to be watchful for suspicious packages or people. "That's always a good thing to do, because it gives people something they can do. It gives them a sense of control. It also builds trust, because he's not overly reassuring people that there's nothing to worry about," Ropeik said.

For a dissenting opinion, check out Slate's article on "Chertoff's bad move." And for a thoughtful view of the good, the bad and the ugly, read MSNBC.com senior correspondent Michael Moran's "tale of three cities."

After 9/11 and after last year's tsunami, there were gripping satellite images of the devastation. This time around, much of the damage occurred underground — nevertheless, commercial satellite firms such as Space Imaging and Digital Globe are making their London imagery available for public perusal. Perhaps closer-range imagery will help authorities catch the perpetrators of the London attacks.

• | Building a better time machine: Time travel is still totally in the realm of science fiction, but it may be just a bit closer to reality if the claims in a newly published research paper hold true. The American Physical Society's upcoming "tip sheet" (No. 49) calls attention to an equation-laden study in Physical Review Letters with the title "A Class of Time-Machine Solutions with a Compact Vacuum Core." (If you're not a subscriber, you can still read a draft on the arXiv Web site.)

APS says that Israeli physicist Amos Ori's scheme "seems to avoid some of the difficulties inherent in other theoretical time machines."

"Like many time machine models, the new proposal requires gravitational fields that curve spacetime in ways that allow observers to travel to their own past," APS reports. "However, unlike previous proposals that have typically required exotic and improbable forms of matter, the new time machine core would consist of a toroidal vacuum embedded in sphere of normal matter. Important questions remain, but at the very least the material required to make the machine exists in our universe."

Ori's paper was mentioned last week in The New York Times' report on time travel, but now you can check out the reasoning for yourself — or just wait for a time traveler to walk through a vacuum doughnut and make any needed revisions.

• | Quick scan of the scientific Web:

• Discovery.com: Covert high-tech security guards commuters

• NSF: Wiring the brain at the nanoscale

• Stanford: Accelerator finds new massive particle

• Scientific American: The mysteries of mass

• | Deeper views of Deep Impact: After scoring an 83-million-mile bull's-eye on the Fourth of July, the scientists behind NASA's Deep Impact mission are sifting through hundreds of pictures of the comet they blasted — and a fresh batch of pictures will be released on Friday.

That's a "witching hour" for the science team, NASA spokesman D.C. Agle told me, because after Friday the researchers start heading back home from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

So far, the fireworks from Comet Tempel 1 have been seen strictly in black-and-white, but even multiple-filter views of the blast wouldn't reveal much color, Agle said. It takes some serious image processing to get the right brightness for the pictures released this week.

"Comets basically have all the light characteristics of toner from a Xerox machine," Agle said. "A comet nucleus is darker than coal."

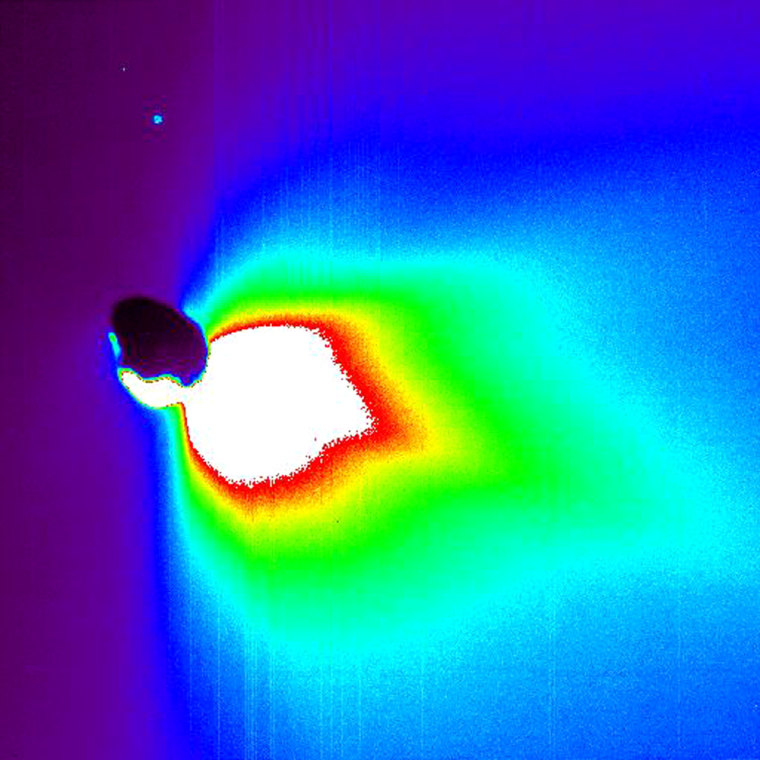

Other imagery uses false color to accentuate certain properties of the comet nucleus and the surrounding coma of gas and dust. Click on these links for a sampling of the alternate views:

- Infrared imagery from Deep Impact highlights temperature hot spots on the comet's sunlit side.

- NASA's Swift satellite provides different perspectives on the fireworks — or should that be "iceworks"?

- An X-ray vision from the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton space telescope shows weak emissions from Comet Tempel 1. But XMM-Newton detected ample signs of water on the comet in optical wavelengths.

- Before-and-after views were captured by the European Southern Observatory.

- An animation based on imagery from Europe's Rosetta spacecraft chronicles the change in Comet Tempel 1's brightness.

- Colorful dust patterns emerge in enhanced views from the ESA's Optical Ground Station.

It's hard to think of Deep Impact without being reminded of "Deep Impact," one of the two cosmic-catastrophe movies that came out in 1997, just after one of the first asteroid scares. The other movie, "Armageddon," made more money — but at the time, researchers thought "Deep Impact" scored a little higher on the plausibility meter. (There are still plenty of scientific bloopers, to be sure, but nothing on the scale of "Armageddon.")

"Deep Impact" was also the first movie release that gave MSNBC a heaping helping of product placement, with Tea Leoni starring as a cable-news anchorwoman. "It almost seemed as if 'Deep Impact' was a made-for-TV movie for NBC," one reviewer complained.

NASA's Deep Impact got much better reviews, from scientists as well as the wider public. However, a couple of Cosmic Log correspondents gave the mission a big thumbs-down, including Mark Lyons from Glassboro, N.J.:

"As a U.S. citizen and taxpayer, I am infuriated that our government would spend $333 million on a useless project such as the Deep Impact mission. $333 million could have fed a lot of hungry children in this world, clothed a lot of impoverished people, or drilled a lot of wells for people living in areas of severe drought. $333 million could have provided better equipment for our soldiers who are fighting terrorism throughout the world. $333 million could have done a lot of good for a lot of people right here on planet Earth, but instead it was squandered in the name of science so that a bunch of puffed-up technocrats can slap each other on the back and say 'attaboy' for having sent a hunk of metal plummeting into the face of a comet."Just exactly how will the average American benefit from the Deep Impact mission? Is it going to fix the traffic jams that most Americans have to contend with each day? Is it going to provide a cure for cancer, AIDS, mental illness? It is going to stop terrorism? I say no to all of this! ..."The advocates of projects such as Deep Impact seem to be driven by a burning desire to learn all about where where life came from. Even if they were able to explain the origin of the universe scientifically, how would the majority of the world's population benefit from this knowledge? Is that going to then equip mankind with the solution for genocide, poverty, hunger, disease, cancer, crime or famine? Any thinking individual knows the answer to that, and it is no!"For all its boasts, science isn't successfully solving this world's problems because science is comprised of flawed human beings who ... are looking for the answers to life in all the wrong places. If anyone wants to know where life originated and where is it going, let them first open the Bible and start reading: 'In the beginning God created...'"

Of course all the endeavors that Mark lists are also worthy of support, and in fact they get a lot more support than NASA. For comparison’s sake, $333 million, stretched over several years of mission development, represents a little more than a day's worth of spending on the global war on terror. The money for Deep Impact went toward supporting scientists, engineers and all the other American workers involved in producing and controlling the spacecraft — and eventually the money re-enters the American economy. Those dollar bills are not shot into space.

Deep Impact might even have a sequel coming up, if NASA can keep the mission on life support for another three years and steer the craft toward Comet Boethin. Over at SpaceRef.com, Keith Cowing lays out the possibilities and urges NASA to spend the "tens of thousands of dollars" required for an extended mission.

Whether or not the mission is extended, Deep Impact is helping scientists take further steps toward understanding the origins of the solar system and, perhaps more importantly in the long run, toward eventually diverting a comet that may someday be heading for Earth (as in "Deep Impact" the movie). We’d all be in big trouble if our inquiry into the workings of the universe stopped with Genesis, and I’m pretty sure God wouldn’t want it to be that way.

• | Robo-racer reserves: Several robotic racing vehicles dropped out during the buildup to last year's first-ever DARPA Grand Challenge — but this time around, the Pentagon has a Plan B. This week, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency listed nine teams as alternates, to be tapped in case any of the 40 semifinalist teams announced last month can't make it to the national trials in September.

Next month, DARPA will rate the nine teams to see which ones have the best chance of getting back in the game. All nine are champing at the bit to get another opportunity to vie for the $2 million prize in the Oct. 8 finals, Grand Challenge program manager Ron Kurjanowicz said in a DARPA news release (PDF file). "One team leader told me his team will be the come-from-behind story of the century," Kurjanowicz said.

We've already listed the 40 semifinalists, so here are the nine alternates: Austin Robot Technology of Austin, Texas; Calculated RISC of Fitchburg, Wis.; Princeton University; Spurrier's Hurriers of Mary Esther, Fla.; Team CART of Bluefield, W.V.; Team Underdawg of San Jose, Calif.; Team White Cougar of Las Vegas; Two Much Trouble of North Berwick, Maine; and the University of Washington.

You can get the rundowns on the teams from DARPA's Web site. May the best robot win.

• | Questions and answers on the scientific Web:

• Universe Today: Can we grow mounds of artificial meat?

• Physics News Update: Why do we think the sky is blue?

• Space.com: When will SOHO spot its 1,000th comet?

• Nature: Which guys have the scent that turns a woman on?

• | Deep questions answered: Mysteries tend to spark more mysteries, particularly when you're dwelling on the deepest mysteries of them all.

That's certainly what happened in the wake of last week's items about Science's 125 top unsolved mysteries and the 100th anniversary of special relativity.

Cosmic Log readers posed their own questions about life, the universe and everything — and because relativity was one of the week's themes, many of those questions centered on the nature of gravity, space and time.

Here are just a few of those cosmological conundrums, accompanied by some partial answers:

S. Behrens, Lynnwood, Wash.: "Is there anything that has ever been discovered that is not in some balance of gravity?"

Yes. In fact, that's one of the top puzzles on the scientific list. Scientists have known for decades that gravity doesn't mesh well with other principles of physics. For example, the movements of galaxies in clusters indicate that gravity is much stronger than expected, based on the observed size of the galaxies — and that has sparked all this talk about invisible "dark matter." More recently, scientists found evidence for a property of the universe counteracting gravitational attraction, known today as "dark energy." Then there's the Pioneer anomaly that seems to be holding back a space probe's progress. On top of all this, gravity is the odd duck among the fundamental forces, sparking the quest for a theory of quantum gravity or the "Theory of Everything." All these problems have led some physicists to suspect that there's something fundamentally wrong with their models of the universe's origin.

Dennis Ward, Seminole, Fla.: "One question that's always bothered me about relativity is the idea of gravity as a warping of space-time. I had this explained to me in my high school physics class as thinking of a flat bedsheet with marbles on it. Each marble would deflect the sheet and other marbles close by might roll down into its deflection, creating a larger deflection. But wouldn't that theory require some force pulling all objects 'down' toward the fabric of space-time? Aren't we just trading one force we can't find for another?"

This "rubber sheet" analogy is one of the most widely used ways of visualizing how mass warps space-time, and we refer to it in our interactive graphic on Einstein's theories. But the analogy has obvious limitations. The basic idea is that the deflection actually represents the "path of least resistance" for an object or light beam passing through a gravitational field, due to the warping of space and time. This presentation on general relativity from ThinkQuest adds an extra dimension (heh, heh) to the concept by drawing a different analogy to carnival rides.

Marc Newman, Houston: "In regards to your article about Einstein, it's worthy of note that we are coming up on the completion of the Gravity Probe B project, which will test some very extreme assumptions about Einstein's universe, namely how massive bodies 'frame-drag' time and space around with them as they spin. You can read all about it at this Web site. NASA and Stanford are remaining mum about the results of the experiment, so keep your eyes on that site to see if Einstein was right!"

Thanks for the pointer, Marc. Here's an archived story that looks back at Gravity Probe B's launch — and this report, based on data from other satellites, hints that Einstein will be proved right again on the twists in space-time.

Richard Cannarella: "What is at the end of the universe?"

No one knows, Richard. We usually think of the end of the universe as the end of the observable universe, which goes out more than 13 billion light-years. But because the light from that distant frontier travels at a finite speed, we're looking back in time as well as out in space. This Wikipedia article explains the distinction between the observable and the actual universe. So there are oceans of space that we can never see. But just for argument's sake, what would happen if you just kept going outward eternally? Some physicists think you would eventually wind up back where you started.

Michael: "This may sound silly, but when did time start? I know time is a human calculation between moments, so I would like to know when time was supposed to have exactly started. Like, how far back, and how old, is time?"

Not silly at all. If we're talking about cosmology (rather than the invention of timekeeping devices back in 3500 B.C.), you could say that space and time started with the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago. I can already hear the follow-up questions: "So what happened 13.701 billion years ago? What existed before the Big Bang?" Most scientists would just shrug their shoulders, or provide hand-waving references to quantum fluctuations and multiverses. In "A Brief History of Time," physicist Stephen Hawking compares such questions to asking what's north of the North Pole. For answers, you can turn to Hawking's "no-boundary proposal" — or to scripture.

William Baal, Rocky Hill: "When our mortal body dies, where does the spirit go? Can string theory show us the way to another dimension? If you believe as I do in a Supreme Being, can science help us get to know him better, and thus where he lives?"

The biological basis of consciousness is one of the top scientific mysteries, but even that question doesn't fully capture the spiritual depths you're after. Can the soul be studied scientifically? I doubt it, but it's certainly humbling to consider that we may perceive only three or four of as many as 11 dimensions in the universe. Check out "The Elegant Universe" for more on multidimensional mysteries. As Hamlet once told Horatio: "There are more things in heaven and earth ... than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

• | More food for thought on the scientific Web:

• New Scientist: Entering a dark age of innovation

• Science News: Mothers know worst

• N.Y. Times (reg. req.): Quantum lessons for evolutionists

• The Ray Kurzweil Reader (and Wayback Machine mirror)

The fine print: Looking for older items? . Share your perspective on cosmic subjects with . If you link to this page, you can use or as the address. MSNBC is not responsible for the content of Internet links.