The similarities between the Challenger and Columbia disasters were so strong — at least in terms of NASA's dysfunctional safety culture — that one accident investigator spoke poignantly of hearing an "echo."

With NASA on the verge of resuming shuttle flights after a 2 1/2-year hiatus, new echoes are resounding, but they're distinctly more benign.

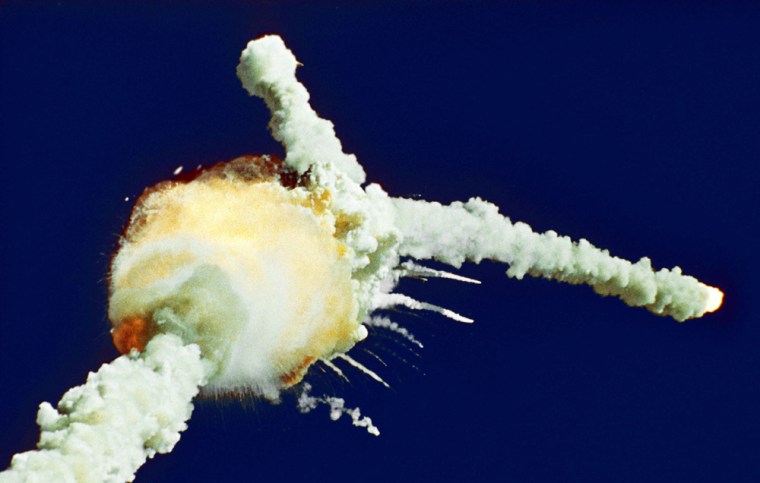

Discovery returned Americans to space in September 1988 after a two-year, eight-month grounding following the Challenger launch explosion. This week, Discovery is poised to return Americans to space again after a stand-down of two years and almost six months. The mission is even taking off from the same launch pad, in the midst of hurricane season.

The first return-to-flight crew had five men. The second crew also has five men — along with two women, one of whom is in charge, commander Eileen Collins.

The two shuttle accidents shared an investigator, Sally Ride, the first American woman in space. She was struck by the way NASA continued in each case to launch shuttles with known problems that could take down spaceships and kill astronauts.

With Challenger, it was brittle O-ring seals in a booster rocket. With Columbia, it was foam insulation falling off the external fuel tank.

"I think I'm hearing an echo here," Ride said while serving on the Columbia Accident Investigation Board in 2003. She was on the Challenger accident commission 17 years earlier.

Collins has compared notes with the commander of the previous return to flight, former astronaut Rick Hauck, most notably about two other common threads: the extraordinary attention surrounding each mission and the stress on the astronauts' families.

There are differences between the two flights, to be sure.

In 1988, Discovery was aloft for just four days. The main objective, the release of a NASA communications satellite, was achieved within hours of liftoff.

This time, NASA is aiming for a 12-day flight. There are many objectives, including a supply drop-off at the international space station, spacewalks to replace broken station parts and test shuttle repair techniques, and the tryout of a brand new boom for inspecting a shuttle heat shield.

In the post-Challenger mission of 1988, once the shuttle safely reached orbit, celebrating broke out.

This time, the tension will continue until Discovery is safely back on Earth.

"Until we come back and land safely and are able to prove that all these corrections that we have put in place and the safety features that we've added can actually work, until you get the final landing, it won't be over for us," said Stephanie Stilson, a NASA manager who led Discovery's latest renovations.

After the Challenger accident, NASA fired solid-fuel booster rockets to test its modifications and repairs. This time, the space agency had no way of fully testing the redesigned fuel tanks, and that means there are more unknowns going into this mission, said Richard Covey, an ex-astronaut who headed a recent oversight panel and who was on the crew that put Americans back in space in 1988.

In 1988, NASA was building Endeavour to replace the lost Challenger and shuttle flights loomed far out into the future. The Hubble Space Telescope and planetary probes were on the launch docket. A space station was in the planning stages.

This time, no new shuttle is on order. The three remaining are to be retired in 2010 to make way for a new spacecraft.

And only 15 to 23 more shuttle flights are envisioned by NASA, all of them dedicated to finishing the space station.