In a strange reversal, astronomers have detected a massive black hole but can find no traces of the surrounding galaxy that should be feeding it.

At the center of most large galaxies, our own Milky Way included, are extremely dense black holes that have masses hundreds of millions times that of the Sun.

Called quasars, these massive black holes are the most radiant objects in the universe, outshining even the brightest galaxies. While the black holes themselves are undetectable, friction and heat from the swirling matter they ingest emit huge amounts of radiation that can be detected by radio telescopes.

To maintain their fierce brightness, however, quasars must feed off the very galaxies they live within. That is why the discovery of a galaxy-less quasar is so surprising.

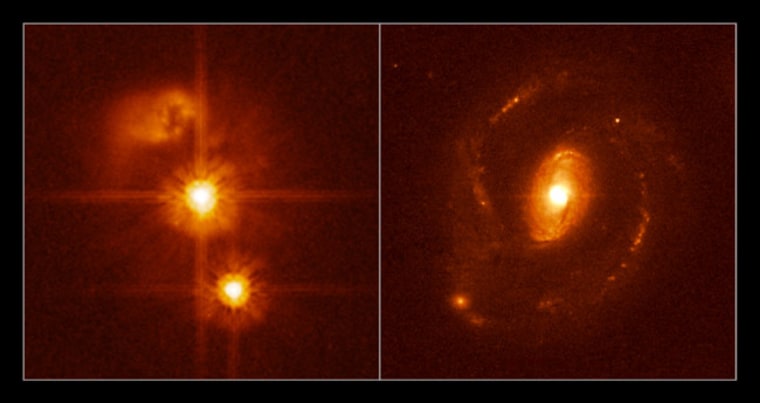

Using images from the Hubble Space Telescope and spectroscopy from the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in northern Chile, an international team of astronomers selected 20 quasars located at moderate distances from Earth to study the properties of their host galaxies.

In 19 of them, the astronomers found encircling galaxies as predicted. But when they looked at HE0450-2958, a quasar located some 5 billion light-years away, they didn’t find any sign of a galaxy.

“We must therefore conclude that, contrary to our expectations, this bright quasar is not surrounded by a massive galaxy,” said Pierre Magain, an astronomer from the University of Liege in Belgium and lead author of a new study documenting the finding.

Quasars are relatively small compared to the galaxies they outshine. They are only about the size of our solar system, but they can emit up to 100 times as much radiation as an entire galaxy.

While the intense brilliance of quasars make them visible from clear across the universe, it also makes detection of their host galaxies difficult because light and radiation from the galaxies get lost in the glare of the quasars.

In the late 1990s, mathematical “deconvolution” algorithms were developed that could be applied to images after they were transmitted to Earth and which were capable of separating light from quasar’s from that of their host galaxies. Since then, astronomers have shown that nearly all quasars are encircled by a host galaxy.

Instead of a galaxy, the researchers detected a cloud of ionized gas about 2,500 light years in size near HE0450-2958. Dubbed “the blob,” the researchers believe this gas cloud is what’s feeding the black hole, allowing it to become a quasar. The researchers estimate that the quasar is siphoning off about one sun’s worth of mass each year from blob to satisfy its ravenous appetite.

Adding to the mystery is the detection of a deeply distorted galaxy located 50,000 light years away from the quasar. This so-called “companion” galaxy appears to be an extremely active stellar nursery, birthing new stars at a rapid rate, and it is also brighter in the infra-red spectrum than most galaxies.

The combination of these three factors — distorted shape, high rate of star production and ultra infra-red luminosity — suggests to the researchers that the companion galaxy suffered a cosmic collision about 100 million years ago, possibly with the galaxy-less quasar.

Such a collision would have stirred up dust and gas and enhanced the formation of stars, said Gèraldine Letawe, a member of the research team also from University of Liege in Belgium. Heat from the seething young stars, combined with dust and gas warmed up by the collision might be responsible for the galaxy’s intense infra-red glow.

To explain the strange cosmic setup they’ve discovered, the researchers have come up with various hypotheses, all of them equally strange:

- It’s possible that the quasar does have an encircling galaxy, but that it is too small and too faint to be detected. If a host galaxy does exist, then it would have be to either six times fainter than typical host galaxies or have a radius smaller than 300 light years. Most quasar host galaxies range between 6,000 and 50,000 light years across.

- The quasar may not have always been galaxy-less, but the collision with the companion galaxy may have somehow caused the quasar’s galaxy to disappear completely. The researchers note, however, that it is “hard to imagine how the complete disruption of a galaxy could happen.”

- The blob could be gas stolen by a slow-moving black hole as it traveled through the disc of a spiral galaxy.

- Perhaps the most intriguing theory is that the quasar is encircled by a galaxy made up almost entirely of dark matter, a theoretical substance which is thought to make up 25 percent of the matter in the universe but which cannot be directly detected using current technologies.

Computer simulations of galaxy collisions might be able to determine if the first two options are plausible, Letawe told SPACE.com in an email interview.

It may be possible to verify whether the galaxy is made up of dark matter by scanning the space around the quasar for evidence of gravity lensing, a phenomenon whereby a massive celestial object warps the fabric of space-time so much that light from distant objects is bent around it.

Another way to test for the presence of a dark matter energy may be to look for gases that appear to be moving as if drawn by the gravity of some unseen object, Letawe said.

The discovery is documented in the September 15 issue of the journal Nature.