A few years ago, any environmentalist who said coal had a place in the energy pie would have been considered a traitor by his or her peers. But a new technology that traps pollutants and emissions tied to global warming has made activists rethink that view.

The technology — called integrated gasification combined cycle, or IGCC — gasifies coal before it’s burned, cutting large quantities of pollutants harmful to human health, such as particulates, small components and mercury, from going up the smokestack.

But the process still costs 20 percent more than traditional coal burning, and that means a reluctance to buy in from industry, which is going through a boom. In the mid-1990s, not one utility had plans to build a coal-fired power plant in the United States. Now more than 120 have been proposed, more in the last 12 months than the last 12 years, according to the National Energy Technology Laboratory.

Environmentalists say they’re willing to buy in — as long as the industry does as well, and goes a step further by also using the process to trap carbon dioxide, one of the greenhouse gases that many scientists fear are contributing to global warming.

“We believe it should be considered the requirement for a modern power plant, but until (carbon capture) happens, this is still just the shiny object that distracts us from the nearly 500 dirty coal plants that are polluting the air,” said Greenpeace energy policy specialist John Coequyt.

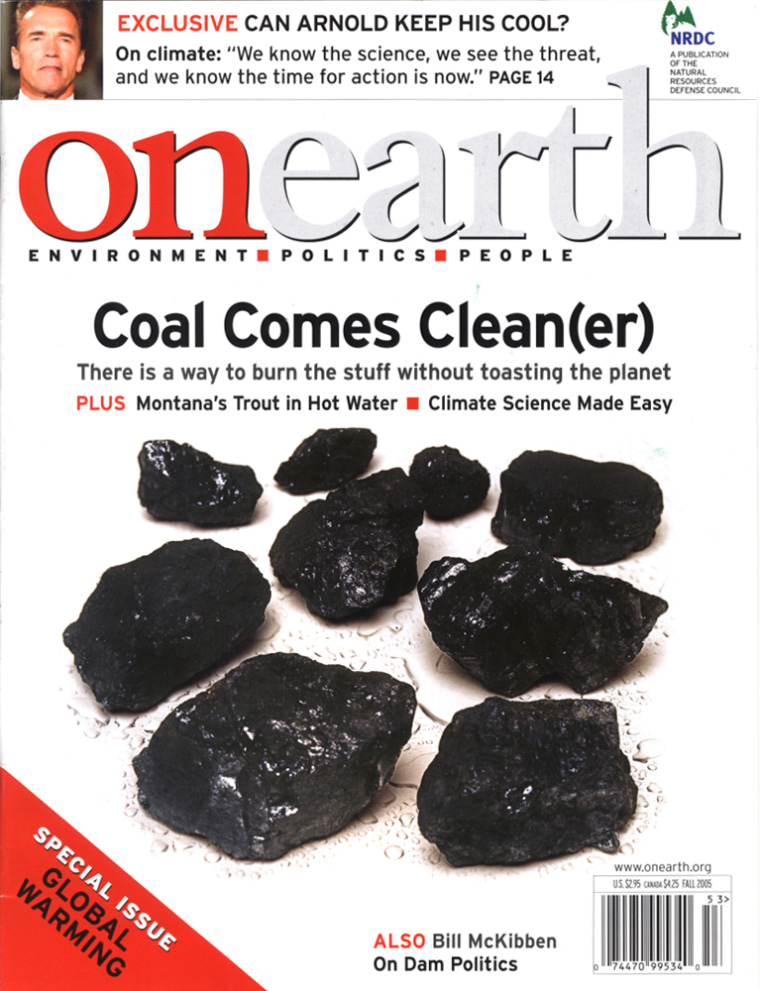

The Natural Resources Defense Council, for its part, placed the issue front and center as the cover story in the fall issue of its magazine Onearth.

“Until coal is replaced with cleaner fuels, we must somehow make it part of the solution,” Onearth editor Douglas Barasch wrote in explaining why the topic was chosen.

Barasch suggested that all sides in the debate need to give a little. “These technologies are available now,” he wrote. “But their broader adoption requires that environmentalists, politicians, energy executives, and coal miners relinquish old habits of mind.”

A carbon trap?

Utility giant Cinergy is big on the process. “This is the way we need to go to preserve the coal option,” said Cinergy environmental strategist John Stowell.

Cinergy and American Electric Power plan to build IGCC plants in the Midwest in the next decade. Both companies are also involved with the U.S. Energy Department’s FutureGen coal demonstration project, which aims to capture carbon.

But they don’t plan yet to add the capturing equipment on the IGCC plants they aim to build.

That concerns some environmentalists, especially as the technology could increase coal use and open up vast areas of high-sulfur coal in the Midwest that the 1990 Clean Air Act made too expensive to consider.

“If IGCC is not built with carbon capture and storage, it may as well be the old dirty stuff,” said Dave Hamilton, the Sierra Club’s global warming program director. “It will be a cumulative increase in our carbon emissions.”

The Bush administration is not likely to require that, having refused to regulate carbon dioxide citing the costs to the economy. “Until there is such a requirement we’re not going to put that technology in place at this point,” said Melissa McHenry, a spokeswoman for American Electric Power.

Incentives might help

IGCC startup costs can run 20 percent over conventional plants, but new incentives could ease the pain.

The new federal energy law contains up to $800 million in investment tax credits for IGCC. Those could help utilities build six to 10 of the first commercial IGCC plants by 2010 or soon after, said Stuart Dalton, a power expert at the Electric Power Research Institute, an industry funded group.

Dalton said those incentives are in addition to billions in other federal coal, gasification and carbon sequestration incentives as well as incentives in Illinois and other states.

“It makes it (IGCC) something people are considering now, even more than six months ago,” he said.

Capturing cheaper with process

According to a recent United Nations report, electricity prices could rise if power plant operators adopt carbon capturing technology.

But it’s also cheaper to add capturing to an IGCC plant than to a traditional one. The former adds only 25 percent to the cost of the electricity, compared to a 60 percent increase for conventional plants, said Ed Lowe, the gasification manager at GE Energy, which develops IGCC units for utilities. (General Electric is a parent company in the joint venture that owns MSNBC.)

In addition, Lowe said, IGCC’s can remove 90 percent of the mercury in coal at one-tenth of the cost as conventional clean coal plants. And GE also aims to halve the startup cost, he said.

It’s also possible that states might try to enact carbon caps that create momentum for carbon capture. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a coalition of nine northeastern states, aims to form regional carbon dioxide markets.

So while utilities don’t yet capture carbon, those with IGCC could be well placed to do so in the future. AEP agrees that over time, there could be cost savings.

“We feel that for the operating life of the plant, 40 or 50 or 60 years, it (IGCC) is the best and most cost effective route to take for customers and shareholders,” said AEP spokesman Pat Hemlepp.