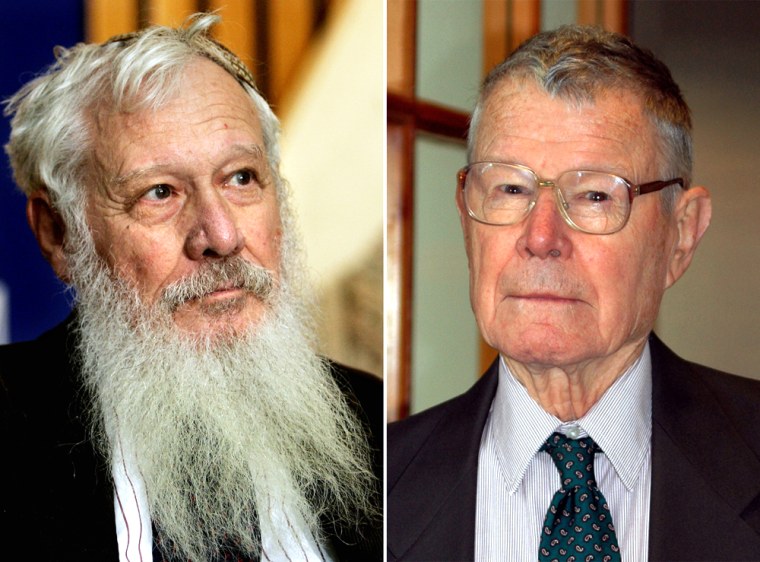

A pair of game theorists who defined chess-like strategies in politics and business that can be applied to arms races, price wars and actual warfare won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences on Monday.

Israeli-American Robert J. Aumann and U.S. citizen Thomas C. Schelling won the award for research on game theory, a branch of applied mathematics that uses models to study interactions between countries, businesses or people.

The theory, devised in 1944 by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, is often used in a political or military context to explain conflicts between countries. More recently it has been used to map trends in the business world, ranging from how cartels set prices to how companies can better sell their goods and services in new markets.

“The understanding of game theory helps explain economic conflicts like price competition and trade wars,” said Jorgen Weibull, chairman of the prize committee. “I think the main impact is on economics, but it also applies to other social sciences.”

Aumann, 75, and Schelling, 84, who know each other but have never worked together, were cited by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for helping explain “economic conflicts such as price wars and trade wars, as well as why some communities are more successful than others in managing common-pool resources.”

It said the pair’s work, which built on research by the 1994 winners of the same prize, could be applied to understand how merchant guilds, international trade treaties and even organized crime groups are formed and operate.

Schelling, who teaches at the University of Maryland, used game theory in his 1960 book “The Strategy of Conflict” to focus on how the U.S. and the former Soviet Union maintained credible threats that were not likely to be used, given the threat of nuclear annihilation.

“If you have second-strike capacity, then it makes your opponent think twice,” said Carl-Gustaf Lofgren, a member of the prize committee.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Schelling said: “I use game theory to help myself understand conflict situations and opportunities.”

He said the prize committee linked the two laureates on the virtue of their respective research.

“They linked us together because he is a producer of game theory and I am a user of game theory,” said Schelling, who worked with the U.S. Marshall plan to rebuild Europe after World War II.

At a news conference in Jerusalem, Aumann had few words of comfort for compatriots wondering when their decades-old fight with the Palestinians would end, although he said he hoped his work could help.

“It’s been going on for at least 80 years and as far as I can see it is going to go on for at least another 80 years. I don’t see any end to this one, I’m sorry to say,” Robert Aumann told reporters when asked about prospects of achieving peace.

Despite his pessimism regarding Israel and the Palestinians, Aumann suggested science could give insight into a conflict that has ebbed and erupted since the early 20th century.

“I do hope that perhaps some game theory can be used and be part of this solution,” the white-bearded academic said in separate remarks by telephone to Nobel officials in Stockholm.

The German-born Aumann lost a son who was serving in the Israeli army during its 1982 invasion of Lebanon, aimed at crushing Palestinian guerrillas.

In the economic world, Aumann (pronounced OW-man) and Schelling’s work is used to prevent illegal cartels between rival companies, Lofgren said.

Two competitors can use game theory to agree on joint price structures that benefit both parties, thereby eliminating fair competition, he explained. But the theory also lets regulators pick up on signs of collusion and, ultimately, break up illegal cartels.

Monday’s award also highlighted developments in game theory that were lauded with the 1994 economics prize to Americans John Harsanyi and John Nash and German Reinhard Selten. Nash was portrayed in the 2001 Academy Award-winning film “A Beautiful Mind,” starring Russell Crowe.

Lofgren said Aumann’s theories differed from Nash’s by introducing an infinite repetition of the same game so as to find the best solution in long-term relationships instead of in a single encounter.

The difference is illustrated in the so-called “prisoner’s dilemma,” one of game theory’s best-known situations in which two partners in crime are put in separate cells and given an ultimatum: If one implicates the other, he may go free while his partner faces a firing squad.

Facing that situation once, both prisoners are likely to talk, meaning both would be executed, Lofgren said. However, if they could repeat the situation an infinite number of times and add the results of each action, they would realize that the best option is for both to keep mum, he said.

That supposition formed the basis for a TV game show, “Friend or Foe?” that aired on the Game Show Network in the U.S.

Aumann is a professor at the Center for Rationality at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Another dual U.S.-Israeli citizen, Daniel Kahneman, won the economics prize in 2002.

This year’s award marked the sixth year running that Americans have won the prize.

Last year’s winners were Edward C. Prescott, an Arizona State University professor, and Norwegian Finn E. Kydland, an economics professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who won for their research on how government policies affect economies around the world and why supply-side shocks like high oil prices can dampen business cycles.

The economics prize, worth 10 million kronor ($1.3 million), is the only one of the Nobel awards not established in the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite. The medicine, physics, chemistry, literature and peace prizes were first awarded in 1901, while the economics prize was set up by the Swedish central bank in 1968.