Back in 1986, with red meat becoming a dirty word in a more health-conscious United States, a group of cattle ranchers gathered in Doc and Connie Hatfield’s barn to talk about finding a new market for their beef.

After hearing from a trainer at a health club, they chose what has come to be known as natural beef — produced without growth hormones or antibiotics, and fed exclusively vegetable feeds — and market it directly to natural food stores, where they could get a premium price.

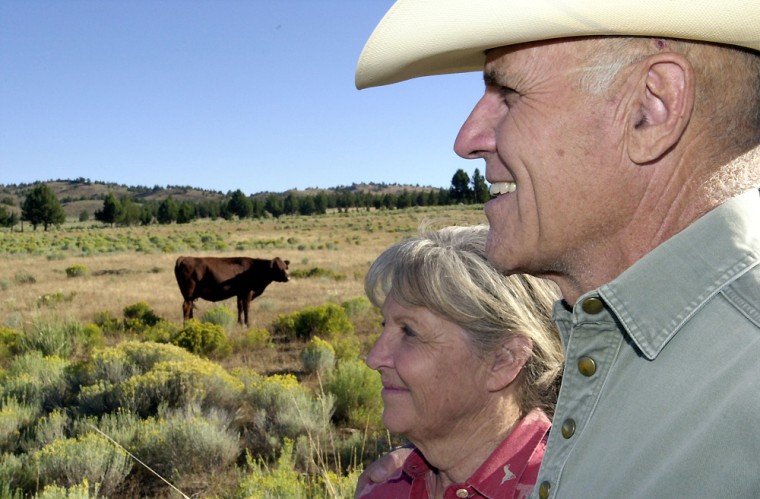

“We were going broke. We were whining about how tough things were,” said Connie Hatfield, one of the founders of the co-op Country Natural Beef, widely sold as Oregon Country Beef. Then “we found out about the market for antibiotic- and hormone-free beef.”

Thanks to concerns about mad cow disease, the success of natural foods stores and Americans’ growing desire to know where their food comes from, natural meat is one of the beef industry’s fastest-growing sectors. Over the past 10 years, Oregon Country Beef has gone from processing 3,400 head a year to 40,000. Since the mad cow scare in 2003, production has more than doubled, with a 73 percent increase over the past year.

Estimated at $500 million to $550 million a year, the market for natural and organic beef accounts for less than 1 percent of overall U.S. beef production, but is growing at about 20 percent annually, while overall beef production of 24.6 billion pounds this year is down from 25.1 billion in 1995, according to the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Under the U.S. Department of Agriculture definition, almost anyone can slap a “natural” label on minimally processed beef. But through the efforts of ranchers and natural beef marketers, natural beef has come to be defined as raised without antibiotics or growth hormones, and never fed the meat byproducts that can carry mad cow disease. Organic beef must meet strict regulations, including the requirement that cattle eat only organic feed.

One of the pioneers and industry leaders is Coleman Purely Natural in Golden, Colo. Chairman Mel Coleman Jr., the company will be pressing the USDA to make the “natural” label for beef more definitive.

“The trend has changed,” Coleman said. “Consumers today have become much more aware.”

The growing demand has moved natural beef into mainstream stores. For example, Laura’s Lean meats are sold in Albertson’s and Fred Meyer stores in Oregon, and shoppers on Fresh Direct, a New York-based Internet grocer, can choose from USDA choice top sirloin steak for $4.99 a pound and Creekstone Farms antibiotic-free choice top sirloin for $5.99.

At the Newport Avenue Market in Bend, Ore., where all the beef sold is Oregon Country Beef, most customers are looking for taste and tenderness, meat manager Randy Yochum said.

But many are also like swim instructor Ulani Levy, whose father is a toxicologist, and who’s concerned about antibiotics in her food and hormones given to cattle to make them grow faster.

“I’ll be eating this the rest of my life,” she said, packages of natural T-bone steaks in her hand.

Still, Coleman said he can count on the fingers of both hands the outfits doing more than $1 million a year in sales.

Michael Boland, professor of agricultural economics at Kansas State University, figures the higher prices paid for natural beef — around 20 percent — are eaten up by the higher costs of raising them. A sick animal that has to be treated with antibiotics drops out of the program and no growth hormone means cattle gain weight slower.

And while it’s easy to get as much as a 70 percent premium for steaks, it is tough to get any more for the end meats — briskets, chuck and rounds, Boland said.

Fast food gets involved

Oregon Country Beef made a key move last year when it made a deal with Burgerville, a Vancouver, Wash., chain dedicated to locally produced and sustainable foods, to produce all their hamburger.

Jack Graves, chief cultural officer for Burgerville, said the chain was looking for a safe source of beef after the mad cow scare in 2003, and held back sales to give Oregon Country Beef time to meet Burgerville’s demand of 35,000 pounds a week.

Oregon Country Beef’s growth has also been tied to getting into dozens of Whole Foods Markets, a chain with 176 stores in the United States, Britain and Canada, and 65 more in development.

The main thing keeping natural beef from going mainstream is distribution, said Fedele Bauccio, CEO of Bon Appetit Management Co., in Palo Alto, Calif., which serves only natural beef at cafes on college and corporate campuses in 26 states.

“These guys are up against the Monsantos of the world — genetically modified products, big agriculture,” said Bauccio. “I think Whole Foods is growing faster than Wal-Mart. I don’t know if they will ever catch them. But there is a huge population that cares about what they put in their bodies.”