Climbing robots and super-strong strings are being put to the test this weekend as part of a $100,000 competition that someday might yield new ways to get to outer space.

It's all part of the Space Elevator Games, the first of NASA's Centennial Challenges to get off the ground. Ten teams from across the United States and Canada will face off at NASA's Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif., in two competitions — one for beam-powered robot climbers, the other for carbon nanotube tethers.

The games are modeled after technological challenges like the $10 million Ansari X Prize for private spaceflight and the $2 million DARPA Grand Challenge. This weekend's purse might be smaller, but there's the same sense of technological innovation, said Marc Schwager of the Spaceward Foundation, the Mountain View group that is managing the contests for NASA. "It's a little more like Kitty Hawk than Kennedy Space Center," he told MSNBC.com.

The inspiration for the contests is the space elevator concept, which in its fullest implementation would call for sending climbers up and down tens of thousands of miles of carbon nanotube ribbon to bring payloads into orbit at dirt-cheap rates. But NASA has emphasized other applications for the technologies as well, ranging from beam-powered space rovers and micro-aircraft to nanotube-composite power cables and building materials.

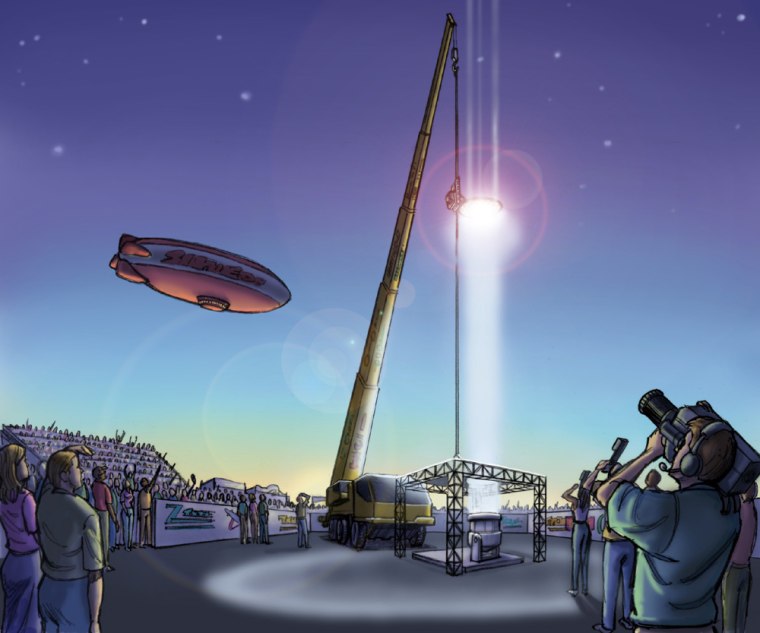

Seven teams are expected to compete in the Beam Power Challenge, Schwager said, which involves time trials for robots designed to skitter up a 164-foot (50-meter) ribbon suspended from a crane. The climbers have to draw their power from a 10,000-watt Hollywood-style searchlight that will be trained on the contraption. The robot that climbs the fastest, with a speed of at least 3.3 feet (1 meter) per second, would win $50,000. The race should be over quickly: At that minimum speed, a robot would take about a minute to climb the ribbon, which is about as high as a 16-story building.

Three other teams, plus one of the teams involved in the climber contest, will face off in the Tether Challenge. In this competition, $50,000 would go to the team whose tether outlasts the others in a pulling machine that Schwager called "a tether torture chamber." To make sure the winning tether really represents a technological leap, it will have to show a 50 percent improvement in breaking force over commercially available products.

"They're insanely strong," Schwager said of the tether material. "Something the size of a human hair can pick up a human."

A technological twist

Unanticipated technological twists are part of the rationale for the Centennial Challenges, and there's already been a big one in the climber contest, Schwager said. While some of the robot-building teams are powering their creations with photoelectric cells, as expected, two teams have built unorthodox Stirling engines that feed off the 10,000-watt beam's heat rather than its light.

"They convert the heat that comes out of the searchlight into mechanical action, then they use that mechanical action to climb the ribbon," Schwager said.

Michael Fischer, a leader of one of the Stirling engine teams, told MSNBC.com that he went with the external combustion engine because it can attain efficiencies of up to 40 percent, compared with the 10 to 20 percent maximum efficiency of photoelectric cells. "Theoretically, I've got twice as much energy to start with than anybody else," he said.

He noted that NASA researchers have been working on Stirling engine technology for powering deep-space probes. "I'm thinking if it's good enough for NASA, it's good enough for me," he said.

Fischer won't have the field to himself, however: The Maryland-based StarClimber team, headed by Matt Abrams, is also pursuing a Stirling approach.

Who else is coming?

In addition to Fischer's California-based team and the StarClimber effort, these teams will be going after the Beam Power prize:

- University of Saskatchewan Space Design Team, headed by Edwin Zhang.

- Team Snow Star at the University of British Columbia, headed by Steve Jones.

- Team Speco, based in Chicago and headed by David Schutt.

- Centaurus Aerospace of Salt Lake City, with inventor Flint Hamblin as team leader.

- The SpaceMiner Project, based in Dallas-Fort Worth and headed by Vincent Lopresti.

New Orleans space enthusiast Michael Flora, who is working with the SpaceMiners, would have had his own entry in the competition if it weren't for a little thing called Hurricane Katrina. "His climber got washed away, and so he joined forces with another team," Schwager said.

Centaurus is also entered in the Tether Challenge, along with a team headed by Bryan Laubscher, a researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory; and two Seattle-based teams, Tethers Unlimited (led by Robert Hoyt) and the Carbon Neanderthals (led by David Lang).

"Each one of these teams is a little microcosm of engineering and science," Schwager said.

There's always next year

Schwager said this year's contest is likely to be just the start, if competitors learn from each other the way they did in the initial stages of the X Prize competition and the DARPA Grand Challenge. "The same thing is going to happen here," he said. "People are going to learn a lot."

The stakes get higher next year, with the total prize money going up to $300,000. The winner in each of the two challenges would get $100,000, with $40,000 going to the second-place team and $10,000 to the No. 3 finisher.

"We've got over 20 teams already signed up for next year," Schwager said. "I don't know whether it's because the prize money is higher, or we've done a better job getting the word out."

There are limited opportunities for the general public to watch the Space Elevator Games on Saturday and Sunday from Orion Park, within sight of the competition area at NASA's Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif. For details on the schedule and directions, check the Spaceward Foundation's Elevator 2010 Web site.