There might be more on your music CDs than you think.

Lurking on some music disks is the recording industry's latest attempt to stem the tide of music piracy -- software that limits the number of times music CDs can be copied.

The special software has been in use for some time on select CDs. But last week, a security researcher unmasked one such program clumsily hidden on some music fans’ computers after they listened to CDs produced by Sony BMG, the world's second largest music label.

Sony BMG has taken a pounding ever since: From bloggers, security firms, class-action lawyers threatening lawsuits, even international digital rights organizations. Online gamers figured out a way to use the software's unique cloaking technology to cheat each other; computer hackers released viruses that attacked PCs, hiding behind the software.

Finally, on Friday, Sony announced it would suspend production of CDs with the technology.

But the disclosure and the controversy have opened anew some basic questions: Whose PC is it? Whose music is it? And it reminded music lovers and computer experts that the recording industry isn't stopping the piracy fight with successful shutdowns of file-swapping sites like Grokster. The battle is hitting close to home.

The dust-up

Nine months ago, Sony began deploying copy-limiting software on about 20 albums. Anyone who dropped one of these CDs into a PC was forced to install a special music player to hear the tunes. But with that software came another program designed to silently watch the user for illicit CD copying. The program, produced by UK firm First 4 Internet Ltd., went unnoticed for months -- in part because it employed a special cloaking technology that made it invisible to most users.

But Internet security specialist Mark Russinovich outed the software while inspecting a recent CD purchase, Get Right with the Man by Van Zant. Russinovich says Sony’s software was sneaky, and it was being installed without consumers' knowledge. The program secretly consumes processor time, and thanks to its constant anti-piracy vigilance, it even prevents a computer from entering power-saving “sleep” mode.

“It was totally hidden,” Russinovich said. “You are paying a price, but you don't know it.”

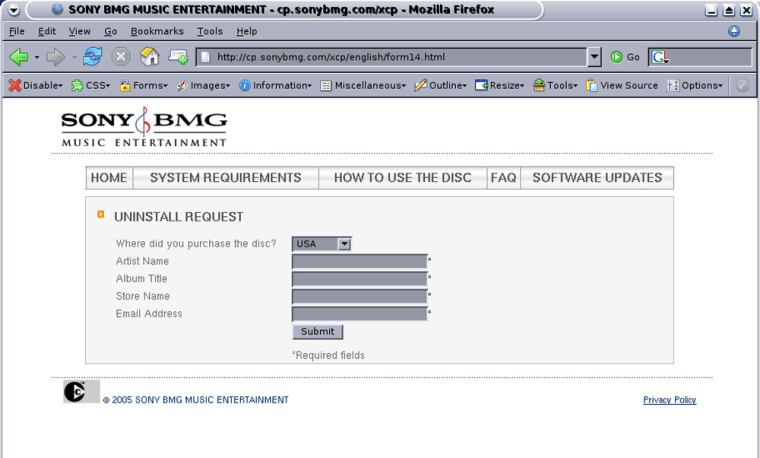

What's worse, Russinovich found that the method First 4 Internet used to hide the program could also be used by hackers to hide other programs on PCs. The computer security world erupted with complaints; Sony backtracked a bit, announcing it would release a fix for the program that un-cloaked it. But what about users who just don't want the software on their PCs? They have to fill out an "application" to uninstall it, according to First 4 CEO Mathew Gilliat-Smith.

And removing the software has consequences, including preventing a user from playing the CD on their PC.

“This is totally unacceptable. It’s crossing the line of what companies should do,” said Richard Smith, a computer security expert. “Most people who buy an audio CD would never dream they’re getting software like this.”

The Electronic Frontier Foundation published Titles include Neil Diamond's 12 Songs and Celine Dion's On ne Change Pas.

Internet bloggers and computer security firms quickly piled on, attacking Sony’s program and response. But digital rights expert Eric Goldman, who says he has mixed feelings about copy protection software, says Sony may have been treated a bit unfairly.

“Some of the public beating of Sony can be attributed to pent-up frustration with digital rights management,” he said. People who don’t like CD copy-limiting software are using this incident as their big opportunity, he said.

Is all copy protection bad?

And, after all, First 4 software is hardly the first copy-limiting program in use. In fact, it's a bit player among Sony BMG albums. Similar copy-limiting software authored by Arizona-based SunnComm Technologies Inc. called MediaMax came loaded on a No. 1 hit album last year by Velvet Revolver, ironically titled Contraband.

That software is now on about 20 million Sony BMG music discs, said SunnComm CEO Peter Jacobs. Most can be copied 3 or 4 times before the software stops the consumer, he said.

Jacobs says people just have to get used to music CDs behaving like software CDs. Consumers now expect to enter some kind of key or serial number when installing software. These prevent a consumer from stealing by passing the CD around to friends. Music CD copy protection programs have a similar effect.

As with software, Jacobs argued, music fans don’t own the music they buy, they merely have purchased a license to use it.

“You agree to a set of conditions (when you buy it),” he said. “There’s a sticker on the outside of the CD that says it's copy protected, and comes with some limitations on how many times it can be copied."

While the tools might not be perfect, they are a step in the attempt to at least slow down would-be music pirates, said Sony’s John McKay.

"There are incredibly high levels of music piracy," McKay said. "Sony has created a series of speedbumps to piracy."

Even Sony's detractors say the company has a right to try to reign in piracy. Princeton University doctoral candidate J. Alex Halderman published a paper two years ago with trivial instructions – essentially, holding down the shift key while inserting the CD -- for defeating an earlier SunnComm anti-copying program. SunnComm threatened to sue him but eventually backed off.

But Halderman concedes companies like Sony are in a tough spot.

“I am very sympathetic to the desire not to have copyrights infringed,” he said. “But in this case, the solution they are trying to apply is creating new problems.”

Door opened for hackers

The new problems, according to computer security experts, were severe. First 4's flawed program opened the door to hackers by re-writing part of the Windows operating system, hiding from view every file that began with the characters $sys$. The strategy troubled anti-virus firms, which said it could prevent their programs from finding some computer viruses. First 4’s Gilliat-Smith said he doubted the severity of the vulnerability, but still agreed to publish a fix that removed the rudimentary cloaking technology. Concerned consumers can download the patch from Sony or get it from their antivirus providers, he said.

“This is a tempest in a teacup,” Gilliat-Smith said. “It’s not designed to be sneaky. It’s meant to be a bar that makes it a little more difficult to circumvent.”

Ero Carrera, a virus researcher at F-secure Corp., disagreed. Consumers around the world now have the First 4 Internet program on their PCs. Many still might not realize it; and even those that do are unlikely to download and install the patch – consumers often don’t install patches from software makers.

The release of computer viruses using the $sys$ cloaking trick have blunted Gilliat-Smith's argument a bit, though there is no indication that any of those programs have infected multiple consumers' computers.

Give me my hard drive back

Still, Sam Curry, vice president of eTrust security management at Computer Associates Inc., says people are tired of seeing their PCs loaded up with unwanted and unexpected software – adware, spyware, Trojan horses.

“It’s time to say enough is enough. You invest $2,000 in a computer, you have the right to decide what’s on it,” he said. The music industry has piracy problems, but shouldn't “try to resolve those issues with ill-conceived attempts to control the users’ computers.”

Or, as Goldman puts it: “The outrage reflects frustration with software vendors deciding what's on your computer. People are beginning to say, ‘Stop it. Give me my hard drive back.’ ”

Bill Rosenblatt, editor of the newsletter DRM Watch and author of Digital Rights Management, says music CDs were never designed to stop 21st Century pirates, and now is not the time to start. "My opinion is that the record label people who use this technology are being told that it works and that it will solve their piracy problems whereas in fact neither is the case. It doesn't work well and it doesn't solve piracy problems.”

Jacobs insists SunnComm technology does work, and says the firm rarely gets complaints. The complaints that do arrive are almost all focused on the fact that MediaMax software doesn’t allow songs to be transferred to Apple iPods. That, he says, is more than a quirky problem, but the firm is close to settling compatibility issues with Apple.

Still, Jacobs worked hard to distance his product from First 4 Internet's; SunnComm's MediMax clearly tells consumers what it's doing, he said, and it opens up none of the security holes left behind by First 4.

Testing it on the public

But there are other problems with copy-protected CDs; Halderman said. To play them on a PC, the user must have administrative rights on that computer, so the necessary software can be installed. That means some employees can’t listen to their CDs while at work. That’s a restriction few consumers imagine when they purchase music.

On the other hand, a simple Google search will tell a would-be pirate how to defeat the copy-protection technology, Halderman said, creating the scenario copy protection critics fear: honest consumers are hassled while criminals continue unobstructed.

“There’s no really good way of testing this stuff,” Rosenblatt said. “In effect, they are testing it on the public.”

But while the kinks are being worked out, Sony and First 4 have had little success putting last week’s controversy behind them. Discussion and criticism continue on Russinovich’s blog, and each day brings word of new computer viruses and lawyers attacking the program. Russinovich said the patch designed to fix First 4’s software tends to crash computers. Computer Associate's Curry took exception to Sony BMG's requirements for uninstall. Users can’t do it alone -- they must go to Sony’s Web site and fill out a form. There, they have to supply a name, e-mail address, and the place they purchased the CD.

“Why is it that they are asking for (this information). This policy wasn't stipulated up front,” he said. It's not about digital rights management, he said, but rather “This is really about their paying customers and rights they have.”

By announcing it would suspend use of First 4 for now, Sony has taken one more step towards appeasing critics. It's not clear that they will be satisfied. After all, there's still the matter of patching all those computers which already have the cloaking software installed.

But one things seems certain after last week's dust-up: More arguing over both music and rights is sure to follow.