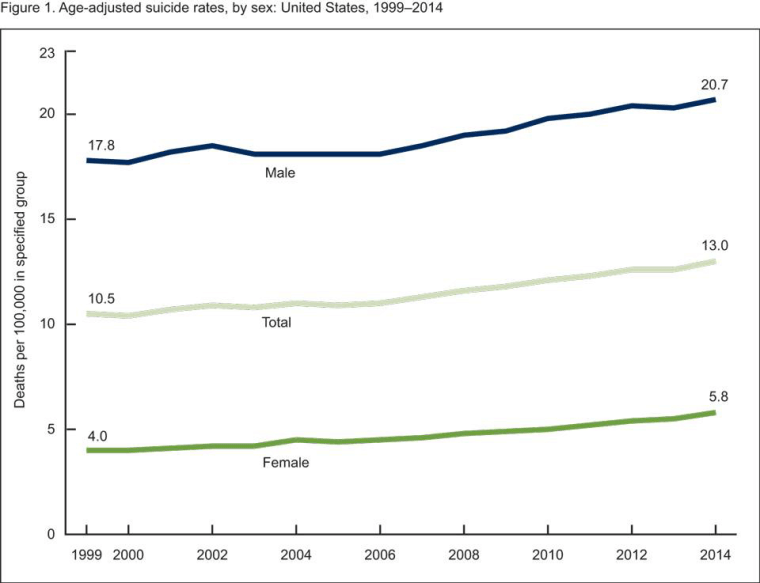

Every day in the United States about 120 people commit suicide. At nearly 45,000 suicides annually, it's the 10th-leading cause of death in the U.S. and its rate is increasing year by year, national data shows. Healthcare providers have ways to prevent a suicide attempt, but often they don’t know in advance who needs the intervention most.

“We’ve been doing this for 50 years, and our ability is still at chance level,” says Jessica Ribeiro, a psychologist and researcher at Florida State University.

That may soon change now that researchers like Ribeiro are getting help from technology. Instead of relying on a few well-known risk factors like depression or drug abuse, these new methods help to recognize suicide as a complex phenomenon; an outcome of many interrelated life events. Artificial intelligence is able to understand this complexity and map out the relationship between factors that lead to suicide in ways no human mind can.

“As clinicians, it’s hard to come to terms with that,” Ribeiro says.

So far the results are promising. Using AI, Ribeiro and her colleagues were able to predict whether someone would attempt suicide within the next two years at about 80 percent accuracy, and within the next week at 92 percent accuracy. Their findings were recently reported in the journal Clinical Psychological Science.

This high level of accuracy was possible because of machine learning, as researchers trained an algorithm by feeding it anonymous health records from 3,200 people who had attempted suicide. The algorithm learns patterns through examining combinations of factors that lead to suicide, from medication use to the number of ER visits over many years. Bizarre factors may pop up as related to suicide, such as acetaminophen use a year prior to an attempt, but that doesn’t mean taking acetaminophen can be isolated as a risk factor for suicide.

“As humans, we want to understand what to look for," Ribeiro says. "But this is like asking what’s the most important brush stroke in a painting.”

With funding from the Department of Defense, Ribeiro aims to create a tool that can be used in clinics and emergency rooms to better find and help high-risk individuals.

Related: That Tweet You Just Sent Could Help Predict a Flu Outbreak

But not everyone who commits suicide has an extensive medical record or has ever even walked into a hospital. So another research team is taking a similar AI-powered approach to suicide prediction by examining data from a more ubiquitous source: smartphones. The DARPA-funded company Cogito has developed a mobile app called Companion that automatically gathers data on someone's communication and movement patterns.

“We don’t listen to the conversations, but look at things like how many calls you make, how many miscalls you have,” says Skyler Place, a scientist at Cogito. “We are taking hundreds and thousands of data points, combining them in a way that humans can’t.”

The data is then used to create a risk score that is shown to the clinician. If that score changes over time, the clinician calls the individual to check in and see whether they need additional care. Cogito is currently working with the Department of Veterans Affairs at a suicide prevention center in Denver, Colorado to test the app with veterans who are at high risk for suicide. If the tests are successful, Place imagines more widespread use in a couple of years.

While an AI-powered tool may determine who is at risk of suicide, it cannot predict exactly when they might attempt it. Facebook is trying to solve this problem by using AI to identify potential "suicide or self-injury" posts and show crisis resources to the user. It's too early to know how accurately the platform's algorithm can spot users in danger but the effort is a step in the right direction, experts say.

What happens after someone is found to be at risk is another challenge. Prevention strategies aren't always effective and it can be more difficult to protect high-risk individuals after they leave healthcare settings. To that end, researchers at the University of Vermont and Dartmouth have developed a system for both risk assessment and prevention.

"As humans, we want to understand what to look for. But this is like asking what's the most important brush stroke in a painting."

First, the patients use a tablet-based survey to answer 11 questions that can quickly gauge someone’s suicide risk in the same way a psychiatrist would. In a trial run in Montana, which often ranks near the top among states with the highest suicide rate, the team found 5 percent of people visiting the ER were at high risk. Half of those people had not come in for psychiatric reasons.

“They wouldn’t have been caught if it were not for this tool,” says Bill J. Hudenko, assistant professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth's Geisel School of Medicine.

The risk assessment tool is paired with Proxi, a newly available mental health app that aims to improve wellbeing for people with depression and other conditions. “Proxi is based on the idea that mental health happens outside the direct connection with a clinician, within friends and family who are an individual’s natural support system,” Hudenko says.

If a patient is classified as high risk, a nurse will help them get set up with the Proxi app to create a support system of friends and family, Hudenko adds. “Because we know what is most valuable in suicide prevention is to help them keep connections with others."