In his 1979 bestseller “The Right Stuff,” author Tom Wolfe described astronauts as men endowed with “the ability to go up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and then have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness to pull it back in at the last yawning moment.”

I never saw myself as one of those guys. They were the decorated officers who fought in Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom. They talked about angle of attack and dogfighting, spoke of days when their butts were on the line trying to keep the bad guys from hurting the U.S. But I was never a fighter jock. After a brief career as a professional football player (I'm the only person to have caught a pass in the NFL and in space), I became a scientist at NASA Langley in Hampton, Virginia. I was recruited to join NASA at a time when the space program was trying to diversify its workforce. I never aspired to a life off the ground.

This stuff Tom Wolfe described? How could I have the “right stuff?”

In any case, NASA seemed to like me. And once the pool of 2,500 applicants had been whittled down to 120, I started to think that I actually had a chance of making it into the astronaut corps. The medical exam was more extensive than anything I’d encountered. There was a vision exam and a dental exam. An MRI looked for undiagnosed conditions, and they checked my cardiovascular health. There was a treadmill test to check my endurance level. And every interaction with NASA personnel was an opportunity for the selection committee to better understand your character, through your treatment of others and your ability to get along. Being condescending to the janitor cleaning the bathroom? That would have been a strike against me.

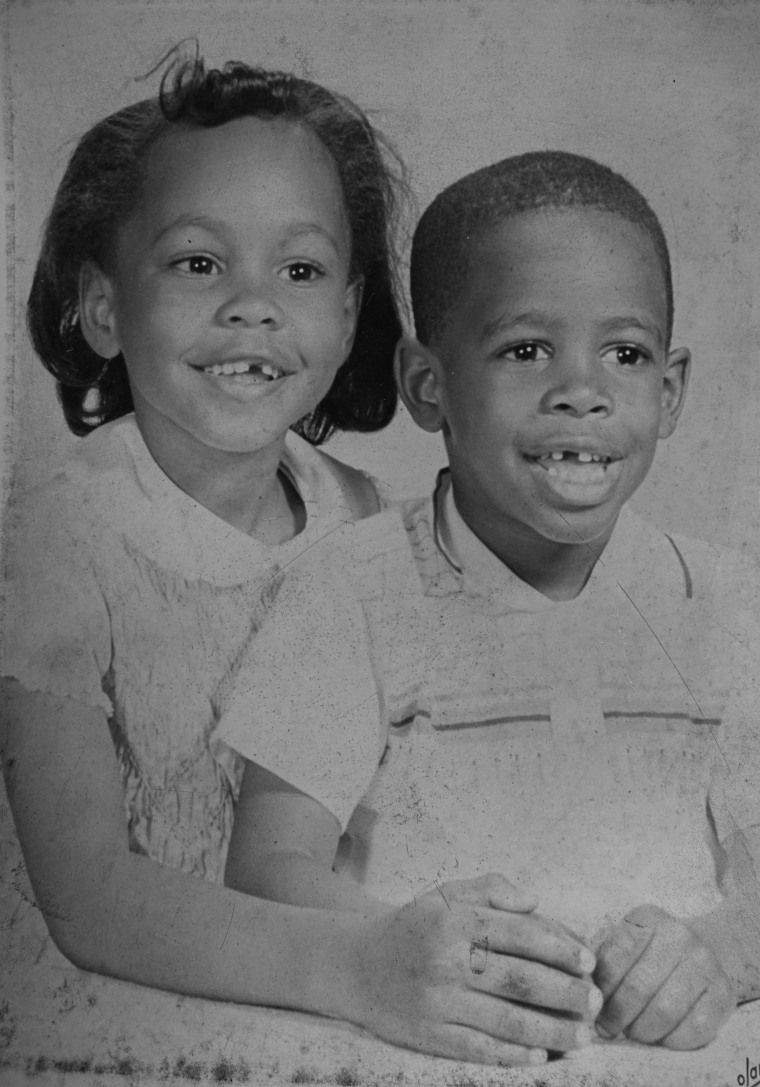

Like the other candidates, I was asked to write an essay explaining what I could contribute to space exploration. I began mine by discussing the values I learned from my parents. When I was five, I wrote, my father drove me to my first Little League basketball practice, where he urged me to work hard, have fun, and share the ball. Those few simple words have resonated in my head countless times throughout my school years and professional life. My parents taught me that virtues like courage, integrity, and faith were assets that would guarantee success.

In May of 1998, I knew that the astronaut selection board was starting to make the calls to applicants. When I got to my NASA office, I had a message from Ken Cockrell, call sign “Taco,” chief of the Astronaut Office. I called him back, but the call got dropped. It happened a second time. I thought to myself, this is not a good sign. But in the end, he said I had been selected.

During the first year of training, the other astronaut candidates and I moved from activity to activity like kids at summer camp. Boats! Planes! Swim lessons! Plus robotics, extravehicular activity training, and survival training in water and on land, and time (lots of time) in the space shuttle simulator. But it was the jet that got me. The T-38 — NASA’s two-seat, twin-engine, supersonic flying machine — has been a fixture at the space center since the 1980s. It trains you to think fast and adapt to changing situations while wrenching through seven G’s, or seven times the force of gravity. It’s one of the closest things to flying in the space shuttle you can experience.

But nothing prepares you for the real thing.

On February 7, 2008, I took the ride of my life.

Our seven-member crew was strapped into the shuttle Atlantis. Astronaut support personnel made sure we didn't bump anything while getting in our seats. They connected us to the oxygen and the chiller that would keep us cool in our suits over the next three hours. The techs handed us our checklists, notepads, and pens. Everything was tethered, in case our gloved hands made us clumsy. After getting situated, we performed a suit check to make sure we had no leaks.

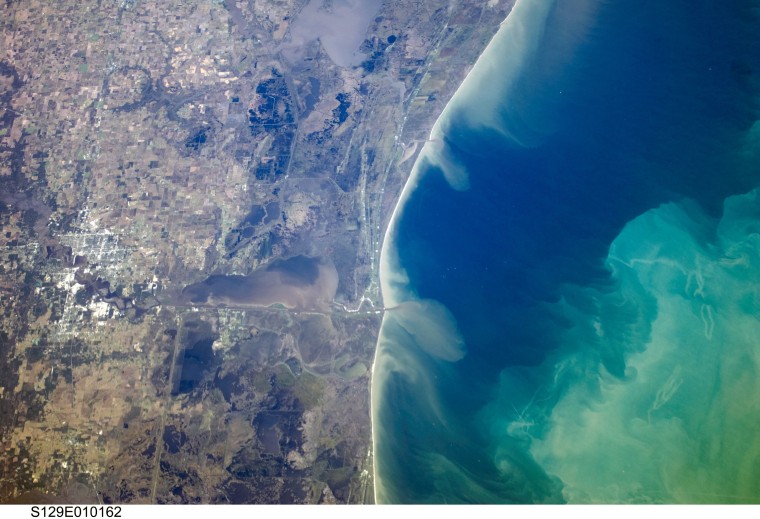

The clock at Cape Canaveral counted down. Finally, the shuttle’s three main engines roared to life. Their thrust tilted us forward and back, a motion NASA folks call “the twang.” Suddenly, there was a wondrous thunder as the solid rocket boosters came alive. We were pinned in our seats, feeling three times our weight on our chests. I labored to breathe during the two minutes before the solid rocket boosters were finally jettisoned. A minute later, we reached 10,000 miles an hour, rocketing over the East Coast with the Atlantic Ocean shimmering in the background. Another five minutes passed as we reached 17,500 miles an hour, fast enough to shut off the engines and jettison the external tank.

When the main engines cut off, I was no longer chasing space. I had arrived.

After the mission was over and I had returned to Earth, a reporter asked what was it like up there. I spoke initially about floating and seeing things that weren’t attached to anything in the shuttle floating around us. But the talk quickly turned to that magnificent view of Earth. I saw our planet for the first time without borders. I thought about all the places where there’s unrest, and here we were flying above all that, working together as one team to help advance our civilization. That was an incredible, incredible moment for me.

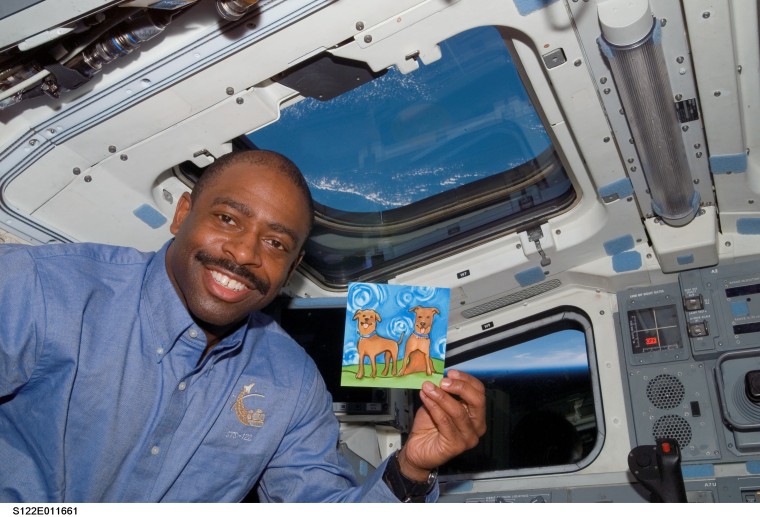

From space, our view of the rivers, seas, and oceans — with all their various shades and pigments —would challenge any painter’s vocabulary. There aren’t enough ways to describe all the different blues in the Caribbean. Turquoise, indigo, azure — I quickly ran out of words. I didn’t think much about color before going to space. Though I appreciate sunrise, sunset, the blackness of the night sky, and the blinding white of snow-capped mountains, I hadn’t anticipated such a stunning array of blue water.

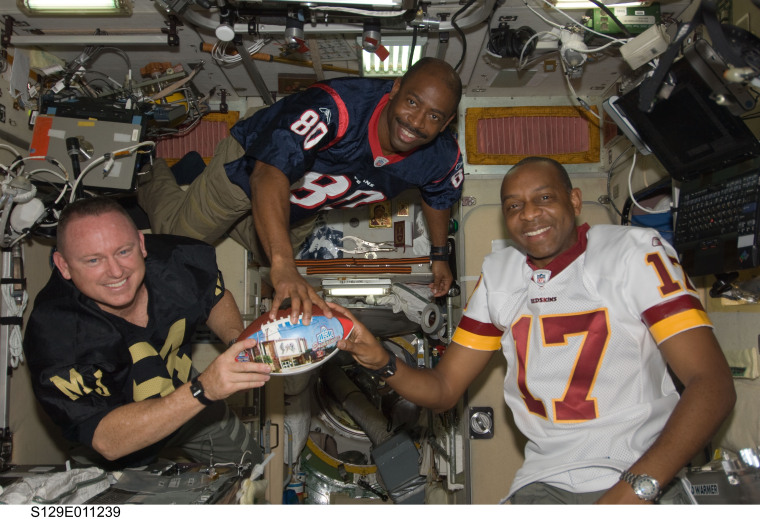

There are many unforgettable aspects of life in space, including the experiments, the robotics, and the spacewalks. But my most memorable moment took place when commander Peggy Whitson and her crew invited us to have dinner in the International Space Station's Russian service module, a large command center with sleep stations. “You guys bring the vegetables, we’ll bring the meat,” they said.

We all congregated around a small table, with some floating above and others below. There we were, French, German, Russian, Asian-American, African-American, listening to Sade and having a meal in space. Out the window, we could see Afghanistan, Iraq, and other troubled spots. Two hundred and forty miles above those strife-torn places, we sat in peace with people we once counted among our nation’s enemies, bound by a common commitment to explore space for the benefit of all humanity. It was one of the most inspiring moments of my life. It changed my perspective on what it meant to be a human, all as one, together.

Adapted from “Chasing Space: An Astronaut’s Story of Grit, Grace, and Second Chances,” published by HarperCollins/Amistad.