What if you could tell you were getting sick because your poop suddenly smelled like bananas? What if your skin instantly changed color if it touched something toxic? Or if certain bacteria dwelling on your skin and in your gut pumped out medicine to help control medical conditions ranging from diabetes to depression?

Such medical advances sound fanciful, but they may soon be in the offing. Scientists working in the nascent field of synthetic biology are exploring ways to coax the tens of trillions of bacteria that live on and in the typical human body — known collectively as the human microbiota — to bring us better health.

“We as an organism are not just human cells…and part of our biology is dictated by our resident microbes,” says Justin Sonnenburg, a microbiologist at Stanford University and a microbiota expert. “These microbes really have their little fingers on the knobs of all of our biological dials — they’re tuning our immune system, they’re tuning our metabolism, they can influence our central nervous system.”

Some bacteria make enzymes that aid digestion. Others train our immune cells to recognize pathogens. Still others influence our mood. But synthetic biologists are exploring ways to use gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 to create “probiotics” that have the ability to secrete medicines or odor-causing chemicals. One day, these engineered bacteria may be available as pills and skin creams.

As Harris Wang, a synthetic biologist at Columbia University, puts it, “We can…introduce new functions to something that has been intimately evolving with our bodies for such a long time.”

A living shield

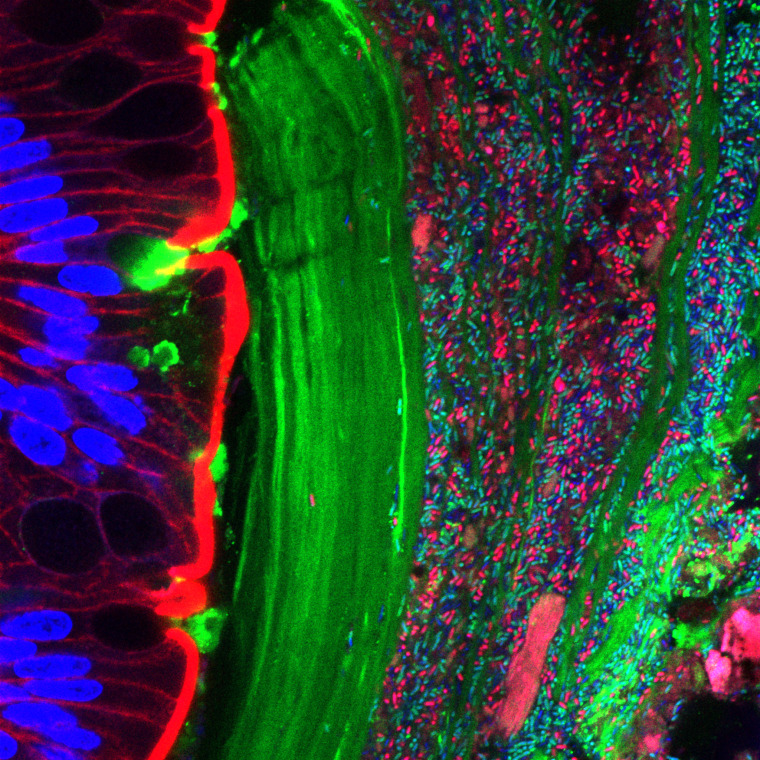

Our native bacteria are already great at picking up subtle changes in their habitats (our bodies) and adapting to survive. In gut-related conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, for example, microbes can sense when trouble is brewing even before a person experiences pain or diarrhea — and then adapt, whether by neutralizing the noxious chemicals, repairing damage to their DNA, or latching on more tightly to avoid being flushed from the body.

“They can detect the little chemicals that are being produced as a result of this simmering inflammation,” says Sonnenburg, who is also co-founder of a San Francisco-based biotechnology company that is exploring the use of engineered bacteria to treat illness.

Engineering these bacteria could be a simple as adding a single gene to give them the ability to make helpful chemicals. So when they sense inflammation, for example, the microbes could secrete substances that curb it.

Another possibility might be microbes that can sense the presence of specific pathogens and pump out chemicals to kill them. “Think of it as a microbial shield against some of these pathogens,” Wang says. Indeed, researchers at Osel, Inc., a startup in Mountain View, California, are working to give bacteria that occur naturally in the vagina the ability to neutralize HIV, the AIDS virus. The company hopes to test a product in humans by next year.

And how about microbes capable of detecting colon cancer? Scientists say these bacteria could patrol the gut in search of cancer cells and then automatically deliver drugs to halt their growth.

Wang points to another possibility: skin-dwelling microbes engineered to warn us of toxic substances in the environment. The germs might change color if you touch a contaminated surface so you’d know to wash your hands.

Similarly, we might be able to coax gut germs to release molecules that give your stool a distinctive odor in response to hidden illness. That way, you’d know you were sick even before symptoms appeared. “If the bacteria detect inflammation, we would want it to produce…a banana smell or something like that that a person would be able to detect when they were going to the bathroom,” Sonnenburg says.

Or your poop might turn fluorescent to indicate inflammatory bowel disease, Parkinson’s disease, or other conditions. That’s the hope of scientists at Harvard Medical School, who recently engineered bacteria in mice to turn blue if the rodents develop gut problems.

Wang says modified microbes might also be able to enhance our mental health. Scientists have observed that some gut microbes produce serotonin and other mood-regulating neurotransmitters. Engineering these microbes to increase or reduce their production of these compounds could give doctors new ways to treat depression and anxiety.

Dealing with Diabetes

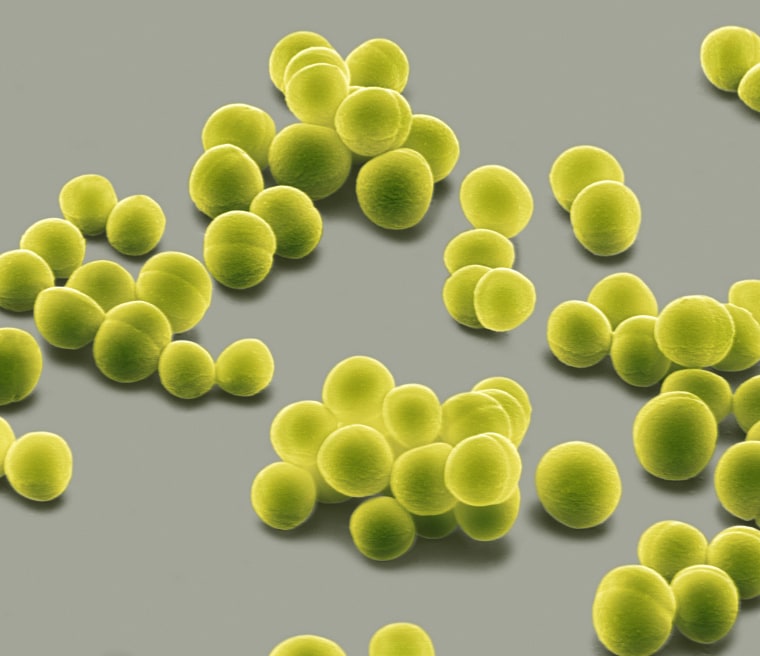

Researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute in La Jolla, California and the University of California, San Diego are working to give a skin-dwelling bacterium known as Staphylococcus epidermidis the ability to sense levels of blood glucose and then pump out insulin as needed to keep elevated levels in check.

If their research bears fruit, people with Type 1 diabetes might be able to control their blood sugar simply by rubbing a cream on their skin — no injections necessary.

The microbes would be engineered so that they could be easily purged and replaced, if necessary. “It’s not a permanent change to your body — it’s sort of a detachable genome,” says Yo Suzuki, a synthetic biologist at the J. Craig Venter Institute.

The team has received funding from Diabetes Research Connection so they can begin engineering the bacteria and test them in human cells and mice. But the research is in its early stages, and many hurdles must be overcome before insulin-producing germ treatment is commercially available. The scientists must determine whether the bacterial insulin is as effective as that produced by the body and whether the engineered germs will be attacked by the body’s immune system, among other challenges.