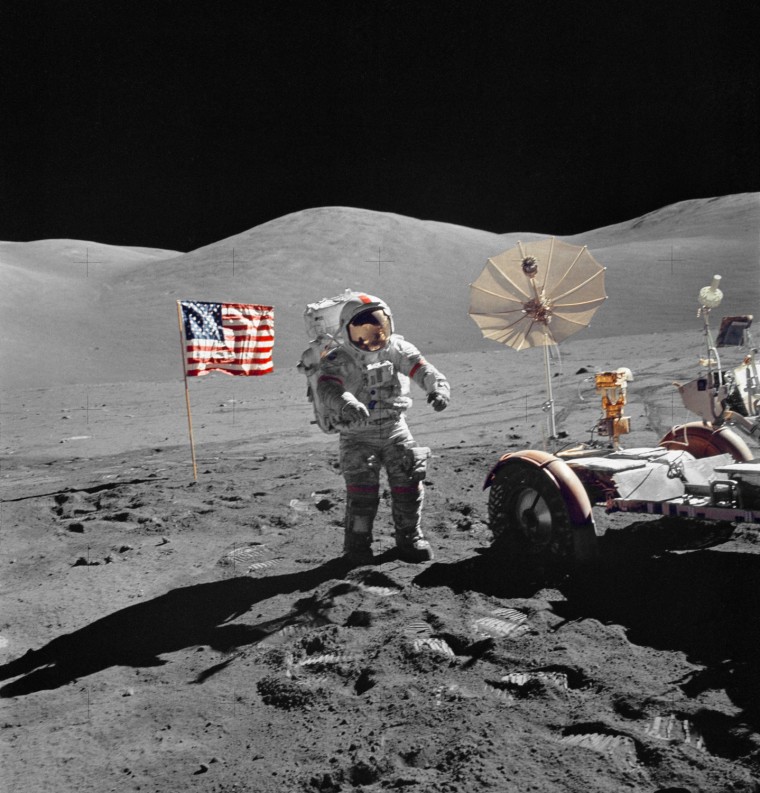

Editor’s note: NBC News MACH has partnered with the American Museum of Natural History to present three documentary films at the Margaret Mead Film Festival, which will be held in New York City from Oct. 19-22. In "Lunar Tribute," Apollo 16 astronaut Charles Duke recounts his 1972 mission to the moon. The film led us to explore what plans NASA and other space organizations have for sending astronauts back to the lunar surface.

Forty-five years after the last moon-walking astronauts blasted off from a chalky-gray lunar valley, the moon is an orbiting ghost town dotted with relics from a once-triumphant space race: six flagpoles (at least one fallen), a statue commemorating dead space pioneers, and a fading family snapshot left on the lunar surface by astronaut Charles Duke at the end of Apollo 16 (see below).

Check back in a decade, though, and the scene may be radically different. In last week’s inaugural meeting of the revived National Space Council, Vice President Mike Pence vowed that “we will return NASA astronauts to the moon,” spurred by scientific, commercial, and national security interests. His comments formalized the moon-first agenda laid out by U.S. Representative Jim Bridenstine, the new nominee for NASA administrator.

“Our very way of life now depends on space,” he declared in a manifesto published last fall. “America must forever be the preeminent spacefaring nation, and the moon is a path to being so.”

In Bridenstine’s vision, the moon will soon host a bustling development of mining operations, robot geologists, video broadcasters, and a small but growing human outpost — all supported by a mix of commercial and government interests. That’s a bold claim, considering there has been only one soft landing on the moon in the last four decades.

But Bridenstine is hardly alone in his starry optimism

Private Competition

The first step of the race back to the moon is already underway. Five teams are vying for the Google Lunar XPrize, which will award $30 million to the first group to land a rover on the moon, drive it 500 meters, and transmit eight-minute high-definition “mooncasts” back home by March 31, 2018. An extra $4 million goes to any group that lands near one of the Apollo sites and sends back video.

Lunar XPrize rules specify that no more than 10 percent of each team’s budget can come from government funding. The diverse set of contestants includes startups from India, Israel, and Japan, along with a Silicon Valley-backed space-exploration company called Moon Express.

This entrepreneurial approach to space exploration mirrors a consensus view emerging within the Trump administration, traditional aerospace contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin, and upstarts like SpaceX.

Prospecting for Lunar Water

Blended in with the new commercial competition for the moon are old flavors of national rivalry. Bridenstine is none too pleased that the solitary lunar touchdown since the 1970s was performed not by the U.S. — but by China.

Chinese rocket scientists put the Chang’e-3 lander and Yutu rover on the moon four years ago. The rover was pronounced dead in August 2016, but the lander was still operating at least three years after landing. In 2018, the China National Space Agency aims to land another probe on the far side of the moon to return samples from a part of lunar surface that has never before been directly explored.

Russia is in the game too, teaming up with the European Space Agency (ESA) on a set of four planned probes that would pick up where Soviet explorations left off in the 1970s. This Luna series would include landers, a lunar-satellite data link, and a surface drilling operation.

Not to be left behind, NASA has been testing the moon-mining rover Resource Prospector, which could launch around 2020. A prototype is now undergoing tests at a proving ground at Johnson Space Center in Houston, where the Apollo missions were directed.

All this activity is fueled by two recent scientific discoveries.

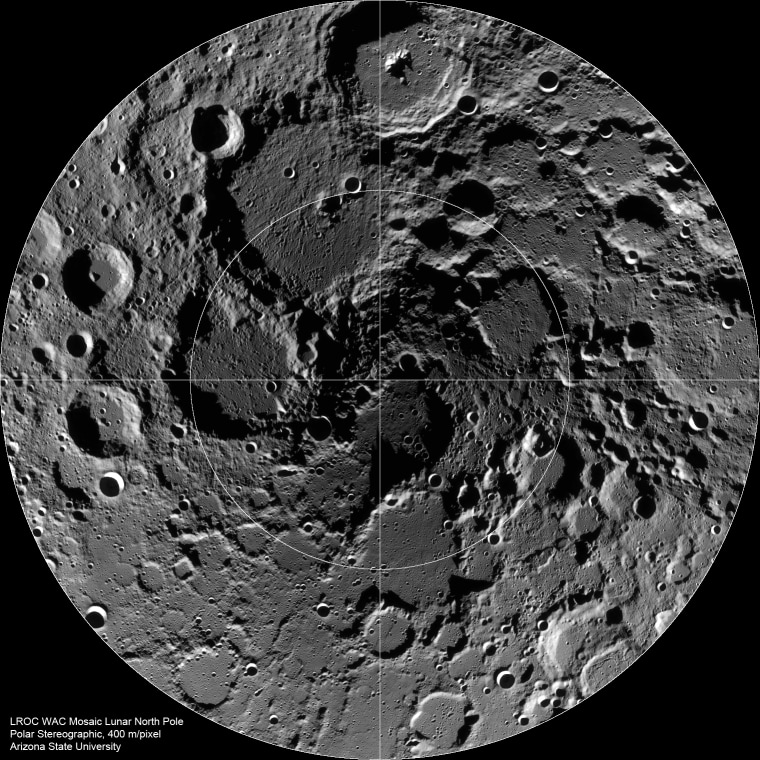

In the mid-1990s, researchers identified mountains and ridges near both of the moon’s poles that bask in continuous sunshine. Placing solar panels near their peaks would neatly solve the problem of how to power a robot — or a human colony — during the two-week-long lunar night.

Even more exciting, space probes recently determined that deeply shadowed craters in the same polar regions contain significant reserves of ice. The implications are huge: Lunar water could be mined for use by residents of a moon base. It could also be easily processed to create hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel.

NASA presumably would be the main customer for the water, but private customers might be interested too.

“We're going to build a propellant economy in space,” says Charles Miller, a longtime space entrepreneur and an advisor to the Trump administration. “We’ll put a fuel station there, and that will drive a virtuous economic cycle in which everybody competes to be the lowest-cost provider of propellant.”

International Moon Station

Mining operations and fuel depots could be automated, but the return to the moon almost inevitably will include human explorers. On the government side, a leaked Trump administration “action plan” proposes bringing astronauts back to the lunar surface ahead of the planned decommissioning of the International Space Station by 2028.

In the private sector, aerospace titans Elon Musk of SpaceX and Jeff Bezos of Blue Origin have floated their own concepts for sending humans to the moon. Notably, both companies participated in the National Space Council meeting.

Last March, Bezos sent the Trump team a seven-page white paper outlining an Amazon-style space-delivery service that would ferry equipment to a water-bearing lunar crater.

Those deliveries might support one of Miller's hoped-for fuel stations, but Bezos also imagines them as a prelude to a permanent settlement.

By the time Bezos made his announcement, Musk had already announced plans to send tourists on a flight around the moon. But at a conference in July, he endorsed a different approach to lunar exploration.

“If we want to get the public fired up, we’ve got to have a base on the moon,” Musk told an enthusiastic audience. Then last month he unveiled plans for a new launch vehicle he calls BFR (for “big f**king rocket”) and released an illustration of it visiting a site he cheekily calls Moon Base Alpha.

The main deterrent to establishing such an outpost is the price tag (Apollo cost about $150 billion in current dollars). Miller co-authored a 2015 study concluding that private competition, off-the-shelf hardware, and targeted goals could drastically reduce both costs and delays.

“We could put the first human steps back on the moon five to seven years from the word ‘go,’” Miller says. An initial landing could be accomplished for $10 billion, he concludes, and a moon base for $40 billion. Such radical economizing would go a long way toward reconciling the Trump administration’s ambitions with its budget, which would cut $561 million from NASA next year.

Unlike mining outposts and XPrize pathfinders, a moon base seems too big and complex for any single company or nation to operate alone. More plausible would be an International moon station, possibly structured as a public-private partnership. The looming challenge, then, may be finding a way to reconcile such a well-zoned sanctuary with a pioneering Wild West of commercial and non-profit lunar experiments.

Jan Woerner, ESA’s director general, promotes the idea of his agency as a lunar matchmaker.

“We have a list of all the actors who are interested in the moon,” Woerner says. “We are connecting them so they can benefit from each other. We are enablers, facilitators, brokers.”

Bridenstine counters that leadership is the more pressing need: “The United States of America is the only nation that can protect space for the free world and responsible entities.”

Resolving these arguments will be key for the long-term development of the moon. But the fact that such points are even being disputed signals that we’re on the verge of a lunar revolution.