This is chapter two of a four-chapter story.

Karen Nyberg was on the space station in 2013 when crewmate Luca Parmitano (#532), out on a spacewalk, called for help. His suit’s cooling system had sprung a leak, and water was filling his helmet. In the weightless freefall of orbit, water doesn’t pool — it forms floating blobs that stick to any surface they touch. Within minutes, water was covering Parmitano’s eyes and nose. He couldn’t see and could barely breathe. He had to get back on board fast before he drowned. But to do that, he needed help from his crewmates.

As Parmitano felt his way back into the airlock, Nyberg floated inside the station, operating the airlock controls. Chris Cassidy (#499), who had been outside working on a different part of the station, joined Parmitano in the chamber. As soon as Cassidy closed the door, Nyberg began repressurizing the airlock.

But the process was agonizingly slow. Parmitano, who had been radioing regular updates on his status to Mission Control in Houston, suddenly went silent. Was he drowning? Nyberg couldn’t tell.

She looked at the air-pressure control and thought about cranking it up full blast to flood the chamber so that they could get Parmitano’s helmet off fast. But she knew that doing so could burst his eardrums — and Cassidy’s, too.

As the pressure inched upward, Cassidy squeezed Parmitano’s hand, and the distressed astronaut gave an OK sign. He was able to breathe, and even talk, though no one could hear him because the water had knocked out the communications link in his helmet. And he couldn’t hear because his ears were full of water.

At last, the pressure equalized. Nyberg flung open the door and quickly removed Parmitano’s helmet so she and Cassidy could wipe the water from his face.

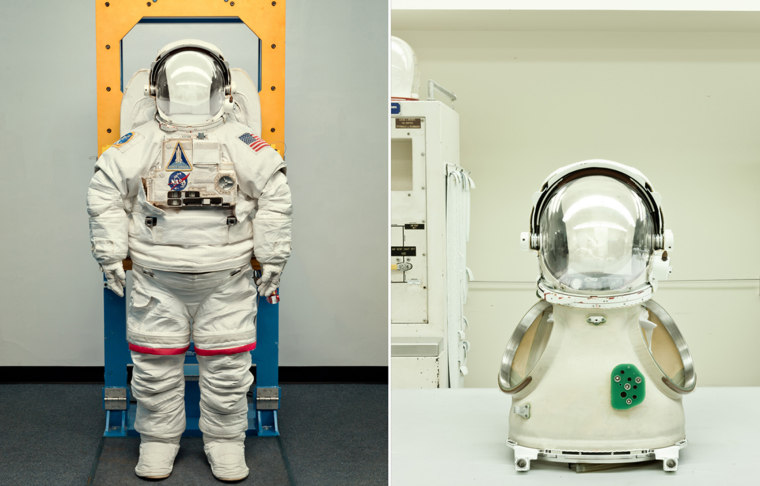

Photo Gallery: Space Travel Up Close and Behind the Scenes

“I was worried,” Nyberg allows, recalling the moment. But her training kicked in: sometimes the right move in a crisis is to avoid extreme action and just follow standard procedure.

Though a water-filled helmet isn’t a likely scenario, airlock operations was one of myriad procedures Nyberg had practiced during countless hours inside a full-sized mock-up of the International Space Station (ISS) at Johnson Space Center. Much of that training focuses on the routine of a “normal” day — exercising, tending to experiments, speaking with reporters and students on the ground, fixing the amazingly complicated space toilet (which has a reputation for frequent breakdowns), and so on.

But at any moment, and without warning, overseers like Michael Jensen, deputy chief of the training branch at Johnson Space Center, can flip a switch to send smoke spewing into the mock space station. Needless to say, if your response is to break a window, you’re not going to impress anyone. You need to don a gas mask and seek refuge elsewhere on the station. “You don't have time to sit there and think about it," Jensen says.

Astronauts have to be good at solving unexpected and often highly technical problems fast. But they also have to follow procedures reflexively and without deviation, as Nyberg did in the near-drowning mishap. You don’t want to share a spacecraft with people who improvise when they don’t need to.

Raised in a tiny hamlet in central Minnesota, Nyberg could hardly be more different from the swaggering test pilots — all male and mostly former military — who dominated the astronaut corps up through the Apollo era. As a girl, she dreamed of working as an astronaut, though she didn’t become a fighter pilot like Virts (who reckons that being a test pilot and the holder of a degree in applied mathematics made him only “about average” as an applicant). Instead, Nyberg became an expert in mechanical engineering, getting a bachelor’s degree with highest honors at the University of North Dakota before heading to the University of Texas at Austin, where she zipped through a master’s degree and a doctorate in the field in just four years. She landed her first job at NASA while still in school — and secured her first patent for robot-friendly space gear.

In 1999, Ph.D. in hand, Nyberg applied to become an astronaut. (Technically, the agency requires only that applicants have U.S. citizenship, an undergraduate degree in a STEM (science, technology, engineering, or math) field, three years’ relevant work experience or 1,000 hours of jet piloting, and the ability to pass a rigorous physical exam.) She made it past the first huge cut of astronaut applicants to get a coveted interview — only 120 candidates got that far in the latest round. After months of additional interviews, tests, and screening, she was in. But eight years of training passed before she would lift off in the Space Shuttle for her first mission. Between that 13-day stint and her time on the space station, Nyberg so far has racked up six months in space.

Nyberg’s long path to space wasn’t easy, needless to say. And as much as she loves the job, it takes a toll on family life. While she orbited the Earth 2,656 times on her most recent mission in 2013 — 166 days and 70 million miles aboard the ISS — Nyberg, now 47, was able to see her three-year-old son Jack only as he toddled around holding an iPad for a half-hour each Sunday.

NASA added that personal video link to help astronauts cope with the tremendous isolation they can feel in space. Loneliness, boredom, and other psychological pressures are among the hardest parts of the space explorer’s job – things that few people outside the agency talk about.

NEXT CHAPTER: Inner Strength for Outer Space

PREVIOUS CHAPTER: The Making of an Astronaut