FAIRMONT, W.V. — This reliably conservative state hasn't been a presidential battleground for decades but it's shaping up to be an important hotbed for the 2018 midterm elections and, possibly, the battle for control of the U.S. Senate.

When President Donald Trump made his way to White Sulphur Springs on Thursday for the annual congressional Republican retreat — his third visit to West Virginia since being inaugurated — he shined a spotlight onto one of his most reliable and supportive strongholds, one that also happens to be a top Republican 2018 campaign target.

In the middle is Sen. Joe Manchin, a familiar figure in a state where he was also a twice-elected governor. But 2018 is a hard time to be a Democrat in this solidly red state and the GOP sees him as a key target, one of ten Senate Democrats up for re-election this year in a state won by Trump.

Manchin's delicate position was evident this week when Vice President Mike Pence used his appearance at the GOP retreat to attack the senator for failing to vote for the GOP tax bill passed late last year.

Manchin fired back:

With the midterm election already well underway, West Virginia will test the rigidness of party ideology, the dedication of President Trump’s base, and whether there’s still room for middle-of-the-road politicians like Manchin to survive on a polarized national stage.

Manchin has not been a stranger to the White House since Trump’s election (he was floated as a potential pick for Secretary of Energy and then voted for a number of Trump’s nominees, including Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, but voted against the GOP health care bills and tax plan).

But this year, the senator is competing to win what could be the race of his political life while also trying to navigate the treacherous waters of Washington's political debates.

He was on center stage in the middle of the recent government shutdown as a primary Democratic player trying to bring opposing sides together and pass a funding bill. And he has found himself in the position of trying to bridge together both parties on immigration policy while simultaneously acknowledging that the issue isn’t of utmost priority to his voters.

“The immigration issue has not been a hot topic in the state of West Virginia,” Manchin said on Sunday’s “Meet The Press.”

“People are concerned, and people want security, and they want to have good opportunities and jobs and on and on and on like everybody else. But it's not been of high concern.”

Since the shutdown, Manchin has repeatedly said Washington, D.C. “sucks,” but last week affirmed that he will indeed run for re-election this year because he’s “trying to make it better.”

Assuming Manchin gets through his primary, he is likely to face one of a number of Republicans vying for their party's nomination, including state Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, U.S. Rep. Evan Jenkins, or Don Blankenship, a former coal baron who went to prison in the wake of a 2010 mine explosion. The Cook Political Report has rated the general election as a toss-up.

To win this year, Manchin will have to prove to the voters who have known him for years that he’s still the centrist deal-maker he says he is while also winning over a large swath of his constituents who voted for President Trump.

Shifting West Virginia

Democrats haven’t won a presidential election in West Virginia since Bill Clinton in 1996. In 2016, it was the site of Trump’s largest election margin in the country, when he defeated Hillary Clinton here by 42 points.

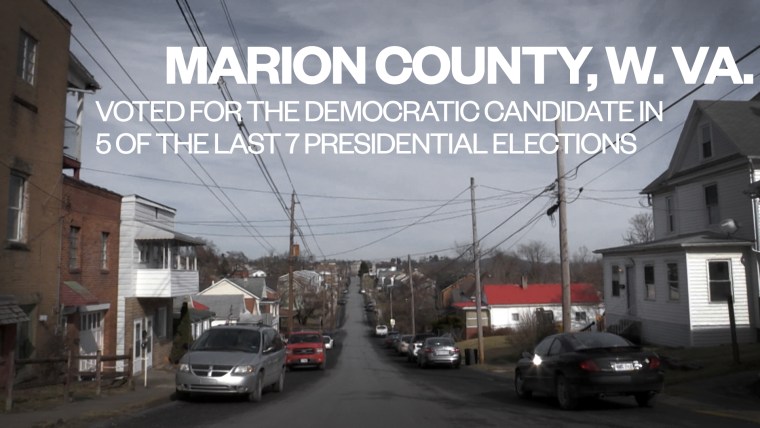

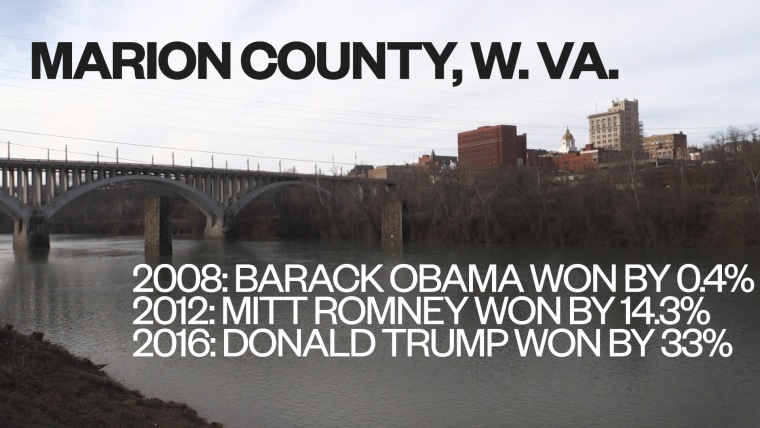

If there’s one part of the region that signals the state’s shift to red, it's Marion County, where Manchin grew up. The senator was born and raised in Farmington, a small coal town in the northern section of the state that’s just outside of Fairmont, the state’s 7th largest city, nestled on a hilly landscape right on the Monongahela River.

Marion County voted for the Democratic candidate in 19 of the 20 presidential elections between 1932 and 2008. In 2008, Barack Obama only won the county by .4 percent of the vote, and then in 2012, Mitt Romney won the county by 14 percent. By 2016, it wasn’t close. Donald Trump easily won the county over Hillary Clinton by 33 percent.

The region is relatively rural, and many residents have been in the area their entire life. In the 2010 census, the county was 94 percent white, with a median income for a household of $38,115 — not far off from the state’s numbers as a whole.

Voters here this week offered a vast variety of grades for President Trump, and most were familiar with their senator, many even noting personal experiences they've had with him over the years.

Taylor Sutphin, who lives in Fairmont and works in the packing and moving business, considers himself mostly a Republican and is thankful for the Trump administration rolling back some regulations he felt were hindering his industry.

Trump is “probably not the best president that we've ever had,” Sutphin told NBC News, “but some of the stuff that he's done when it comes to deregulating DOT makes it a lot easier on my end." Manchin, meanwhile, is “a good guy,” he said. “I can't say anything bad about him because I've done a lot of work for the Manchins. So, they're good people."

Jeff Fleming calls himself a “conservative Democrat,” and praised Manchin’s job as senator in an interview this week. “It’s hard right now to be a Democrat in this country because they’ve tagged it with the far left and that’s not necessarily the case with West Virginia Democrats. West Virginia Democrats used to be traditionally conservative, and I think that’s where he stands, and it’s kind of where I stand.”

When it comes to the president, the “jury’s still out,” Fleming said. “I haven’t drawn a conclusion on him yet. I know he’s gotten a lot of bad press but we’ll see how his policies go. I’ll give the guy time.”

Doyle Cowger, a retired coal miner who has lived around Fairmont all his life, didn’t like Trump or Hillary Clinton in 2016 but told NBC News that he felt Clinton was the better option of the two. He felt the sentiment around his region largely changed during the last election.

The president “knows the right things to say to get elected in this state, but he didn’t say what I liked,” Cowger said. “And I’m a coal miner and I still don’t like what he said.” Cowger voted for Manchin before and plans to again. “He’s working on pensions for the miners and the other labor people and looks out for old people, or seems to.”

If Manchin loses this fall, it could be partly because of voters he's won before that he could not keep for another round. This year, Republicans believe they have extra ammo to unleash in the fight for this seat, including Manchin's support for gun background check legislation in 2013, and his votes last year against President Trump's top legislative priorities.

Carson Zickefoose, a paralegal from nearby Shinnston, “couldn’t be happier” with the president, and is one of those voters Republicans know they might have reached. He’s a registered Republican, but Zickefoose calls himself a “conservative first."

He said he voted for Manchin twice as governor but probably won’t vote for him for Senate this year. “He talks a lot about wanting to work with President Trump and wanting to be part of the solution," he said in an interview.

"But he’s voted against absolutely everything that Trump’s put up."