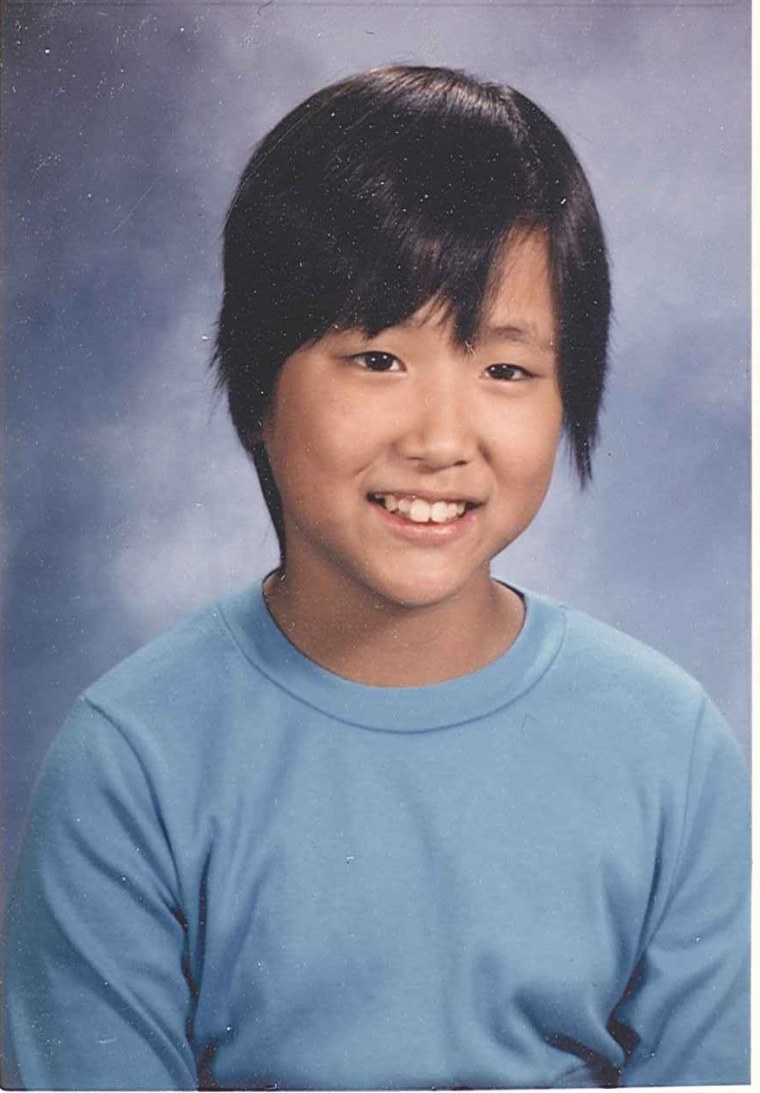

For 16 years, Carol Park spent much of her spare time behind bullet-proof windows at a gas station owned by her parents in Compton, California.

At 10 years old in 1990, she began working the graveyard shift on the cash register at her family's business. But two years after Park's career as a cashier began, riots broke out across Los Angeles after the acquittal of four LAPD officers who were videotaped beating black motorist Rodney King after a car chase.

RELATED: Communities Work to Build Understanding 25 Years After LA Riots

In total, more than 3,600 fires were set and more than 1,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed during the riots, which stretched for six days from April 29 to May 4, 1992, according to the University of Southern California. In total, more than 50 people died and more than 2,000 were injured.

“As a 12-year-old Korean American, I felt angry. I was upset at the violence, which seemed senseless at the time,” Park told NBC News.

“We felt betrayed by our local law enforcement that's supposed to protect and serve. They literally abandoned us and left us pretty much on our own.”

Park and her brother were watching the news after school when they learned about the verdict issued in the King trial. That afternoon, people gathered to protest about 10 minutes away from the family gas station, Park said. As the day progressed, demonstrations became violent and the children grew worried.

Though they were safe at home, their mom was still at work.

Park’s mother made it home safely that Wednesday. But as the riots went on, Park was afraid that her mom might go to the station amid the chaos to see if the business had burned down.

“I remember looking at the charred buildings in the area the weekend after the riots — I was working with mom again at the gas station after the riots ended — and thinking, ‘This is crazy. People are crazy, why would anyone do this to their own neighborhoods?’” she said.

Growing Tensions

The riots highlighted tensions that had been building between the black community and Korean-American community — which calls the riots "Saigu" — for years.

A year prior, a Korean-American shopkeeper named Soon Ja Du had fatally shot a 15-year-old black girl named Latasha Harlins. Du received a sentence of five years probation and 400 hours of community service.

Another incident happened in June that same year, when shopkeeper Tae Sam Park killed 42-year-old Lee Arthur Mitchell. Park refused to sell Mitchell a wine cooler he allegedly wanted for 25 cents less than it was priced, according to the Los Angeles Times.

A struggle ensued after Mitchell went behind the counter of Park’s liquor store to take money, and Park pulled a pistol and shot the unarmed Mitchell five times. Park was cleared in the incident.

And just a month earlier, two recent Korean immigrants working at another liquor store were shot to death after complying with demands from a robber whom police identified as black, the LA Times reported.

“African Americans felt the bite and the squeeze and the pinch of poverty in real serious ways,” 69-year-old Rev. "J" Edgar Boyd, who was pastor of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles at the time of the riots, told NBC News. “There became areas and moments of frustration and tension between those who were marginalized and those who seemed to be surviving — and surviving from the resources of those who were actually pinched and who were impoverished.”

South Los Angeles — one of the focal points of the riots — was predominantly inhabited by blacks at the time, while most mom-and-pop stores in the area were owned by Korean Americans, according to Edward Chang, professor of ethnic studies and founding director of the Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American studies at the University of California, Riverside. By the end of the unrest, more than 2,200 Korean businesses were looted, completely destroyed, or damaged, causing approximately $400 million in damages, according to Chang's research.

Three decades before in 1965, six days of looting and arson occurred during the Watts riots, which broke out following the arrest of a black man for drunk driving.

After those riots, large merchants began leaving the area, which created opportunities for Koreans — who had begun immigrating to the United States after the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965 — to purchase businesses, Chang told NBC News.

Among those was Park's father, who had purchased five gas stations across the southern Los Angeles region by the late 1990s, acquiring the one in Compton in 1974.

Park's father died the year she began working at the gas station. While the family had stations in other cities, Park’s mother sold them and kept the one in Compton because of its sentimental value. It was the first that she and Park’s father had owned.

“At the time, Korea was most homogenous society in the world,” he said. “They had one race, history, language, so they didn’t understand what it means to live in a multi-ethnic, multiracial community.”

Koreans, including Park's family, immigrated to the United States seeking the American dream, but were put in difficult positions, according to Chang.

“At the time, Korea was most homogenous society in the world,” he said. “They had one race, history, language, so they didn’t understand what it means to live in a multi-ethnic, multiracial community.”

By the early 1980s, Korean immigrants began dominating mom-and-pop stores throughout the nation, the same time racial tensions began to grow, according to Chang.

Tensions between blacks and Korean Americans intensified because of what is called the “middleman minority theory,” Chang said. The theory posits that when minorities occupy a middle position, such as a retailer, they function as a buffer between the dominant and subordinate groups. As a result, they become the target of frustration and anger.

“Merchants and customers have built-in conflicts in relations,” Chang noted. “Customers want bargain sales, merchants are going after profit margins. When buyers are poor minority clientele and sellers are very limited English speaking merchants, then that conflict will intensify because of the relation.”

Park experienced racism first-hand, being called derogatory names as she worked at the gas station.

“By the time I was a teenager, I would just say, ‘Sir, if you’re going to be racist, just get it right. I’m not a c***k. I’m Korean. You can call me a g**k,” she said. “I would just get mad and I would fight with my customers. I would call people racist names.”

Chang said it wasn't the Rodney King verdict that was ultimately responsible for the riots, but a culmination of rising tension due to the growing gaps between blacks and whites, haves and have-nots, and police brutality.

“They really expected a guilty outcome,” Chang said. “They had proof this time, so they thought for sure this time the police officers [would be found guilty]. They’d been complaining about police brutality for years. And finally there was proof, and yet it didn’t matter.”

Damage and Rebuilding

While the riots were taking place, Park's mother worried about the state of the family's gas station. When she finally made her way to Compton, she found that it had been spared from major damage, Park said.

But businesses across the street weren't so lucky. A complex that was home to a doughnut shop and a market, among other establishments, was reduced to a pile of rubble and ash.

RELATED: Justin Chon Explores ‘Untold Aspect’ of LA Riots in Film Called ‘Gook’

Business owners in nearby Koreatown were also victims of looting and arson. In a memoir she released this year, Park recalled that the neighborhood looked like a “war zone” where hundreds of buildings had been burned. Police weren't responsive to calls from the community in the area, leaving Korean Americans to fend for themselves.

During the riots, Sonny Kang joined the LA Korean Youth Task Force, which went out to help business owners who didn't have enough employees defend their stores, he said. Radio Korea became the lifeline for members of the community, who would call when they needed help.

“We felt betrayed by our local law enforcement that's supposed to protect and serve,” Kang told NBC News. “They literally abandoned us and left us pretty much on our own.”

Kang remembers driving down surface streets at 70 miles an hour with seven other people in the car and shot guns hanging out of the window. When a police car pulled up to his vehicle to see what was happening, Kang thought he was going to prison.

RELATED: ‘April’s Way’ Captures Stories of Korean-American Merchants During L.A. Riots

“Then the cop looks at us, salutes us, and then drives away,” he said. “That's how I knew the city was literally at war. That would never happen any other time, where a cop would see a car with guys holding shotguns and just drive away.”

In the years following the riots, the Korean-American community banded together to rebuild.

The Korea Times newspaper raised $3 million to help riot victims in the immediate year afterward, according to the LA Times. And during the decade afterward, the nonprofit Korean Churches for Community Development (KCCD) raised money and trained community members in how to rebuild and purchase property.

25 Years Later

Park, who is now a researcher at the Young Oak Center for Korean American Studies, said that there is greater coalition building between blacks and Korean Americans today, and that the Korean-American community has learned that they needed to be more visible in the fabric of American society.

Koreans began to identify themselves as Korean Americans after the riots, Chang said. He added that while the primary goal for Koreans when they first arrived in the U.S. was to achieve the American dream, seeing how the community suffered and how nobody came to their rescue made them realize the importance of becoming politically active.

“They learned a valuable lesson that we have to become much more engaged and politically involved, and that political empowerment is very much part of the Korean-American future,” Chang said.

“I remember looking at the charred buildings in the area the weekend after the riots ... and thinking, ‘This is crazy. People are crazy, why would anyone do this to their own neighborhoods?’”

In 2013, LA elected its first Korean-American city councilmember, David Ryu. Ryu said the riots were a wake-up call not only for himself, but for the country.

"Now more than ever, it is important to understand that pitting groups against one another will always fail,” he told NBC News by email. “Our work toward achieving racial equality is far from over.”

And earlier this year, congressional candidate Robert Ahn beat fundraising and vote expectations to finish in the top two of a primary. In June, he will compete in a run off election to represent California’s 34th Congressional District, which contains Koreatown.

Michael Wu, who was an LA city council member during the riots, told NBC News that despite the progress that has been made in race relations, poverty and the gap between the haves and have-nots remain in LA.

“I wouldn’t say that there could never ever be a riot again,” he said. “I don’t think that LA is immune from some of the racial tensions that we continue to see in other American cities.”

Park agrees.

She said that lack of education and police brutality are problems that remain today, citing Ferguson and Baltimore.

Korean Americans have moved out of South Central Los Angeles, and businesses in the region are now being purchased by Southeast and Arab Americans, Park noted.

“And now you have people being racist and discriminatory toward Muslims. Clearly these things are continuing to happen,” she said. “And I think it's an important time for our nation to really look at the conditions that caused these riots continue to cause riots and what we can do about them.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.