IRVINE, Calif. — A historic site representing one of Southern California’s earliest Japanese pioneer settlements may be in danger of being destroyed in a possible sale, according to activists from the Japanese-American community.

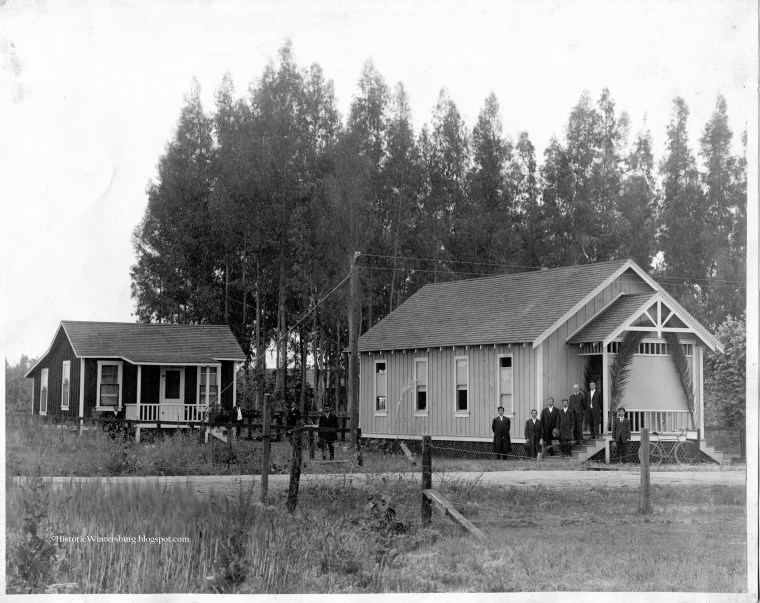

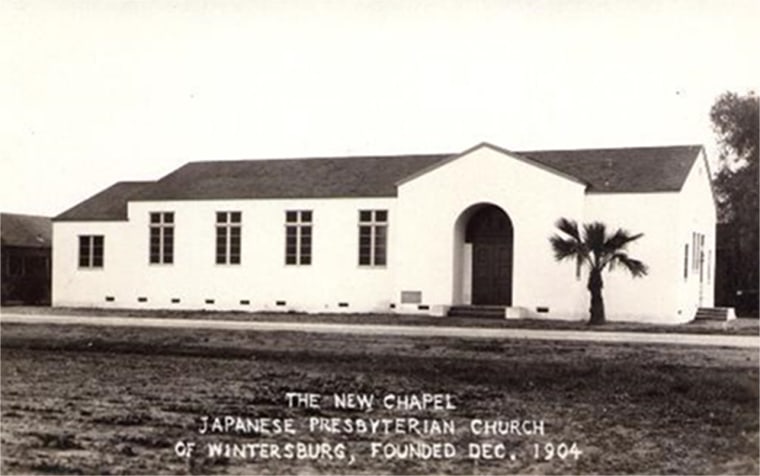

Historic Wintersburg — a 4.5-acre parcel of land in Huntington Beach, California, that includes the original Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission built in 1910 — is up for sale, which could mean that the more than century-old buildings and artifacts will be torn down if the property is redeveloped, Mary Urashima, chairwoman of the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force, said.

They didn’t have social media back then, so the only way you could see your cousin’s kid, or talk to the other farmers about a new fertilizer technique, was at the church

Property owner Republic Services, a waste collection company, offered “informal notice” on Jan. 26 that it is considering selling the site to the self-storage company Public Storage, Urashima said, despite the task force's ongoing efforts to acquire and preserve the site.

Doing so would jeopardize an important piece of Japanese-American history, Urashima added.

“When you look at Japanese-American historical sites that have been saved and preserved, the majority are confinement sites,” she said, referring to incarceration camps, relocation centers, and Department of Justice prisons. “Historic Wintersburg shows us how people lived — it’s the other part of the story.”

Officials from Republic Services declined to comment.

Wintersburg Village — as the property was originally known — once contained churches, residential homes, farmland, and goldfish ponds used to grow fish that were sold to drugstore pet departments.

It was also one of few sites owned by Japanese Americans before the California Alien Land Law of 1913, which prohibited people of Japanese descent from owning property, said Urashima. Today, six buildings still stand intact.

“This really was its own Japantown that became a site where people could come together and have a sense of community in a new place,” Christina Morris — Los Angeles field director for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a nonprofit dedicated to revitalizing historic places that in 2015 named Historic Wintersburg a “national treasure” — said.

During World War II, when approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent were forced into incarceration camps, Wintersburg buildings were boarded up and everyone associated with the property — from the Furuta family that owned the land to the congregants of the mission — were removed from their homes.

The Furutas’ ownership of the land meant that, unlike most Japanese Americans, they were able to return to their property after the war ended. They then reopened the church, built a new ranch house and transitioned the land to a flower farm, which would become one of the largest suppliers of water lilies in the Western United States, according to the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force.

Dennis Masuda, a retired schoolteacher who grew up in Huntington Beach during the 1950s, said Wintersburg Village was a social hub for Japanese Americans after the war.

“They didn’t have social media back then, so the only way you could see your cousin’s kid, or talk to the other farmers about a new fertilizer technique, was at the church,” Masuda, who attended Sunday school there for about 15 years, said. “The ladies would sit inside the church building and talk, and all the guys would be outside leaning on their cars smoking cigarettes, talking about farming, and the kids got to play.”

For Urashima, this post-war history tells an important story of resilience.

“It shows how they regained and restarted their lives after World War II incarceration,” she said. “You have more than 100 years of history in this one little property.”

The Furutas, who owned the property for nearly a century, eventually sold it to Republic Services — then called Rainbow Environmental Services — in 2004 after the third generation of the family attained higher education and moved away from farming as their livelihood.

“It would be beyond the realm of their experience to think that their property would be considered important American history and that people would want to save it,” Urashima said.

Urashima, alongside the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Trust for Public Land, has been working with the city and property owner to buy back the site, restore the buildings and transform the area into a museum, park, community gathering spot and urban farm. The amount offered would be determined after an appraisal of the property’s market value, she said.

“We’re willing to pay for the property, so they wouldn’t be out financially,” Urashima said. “We hope the company will see that this provides tremendous community benefit, and that it provides rare historical value. There’s no other place like it in the country.”

This really was its own Japantown that became a site where people could come together and have a sense of community in a new place.

National organizations including the Japanese American Citizens League — a nonprofit civil rights group — and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles have also joined in the effort to protect and preserve Historic Wintersburg.

“This is one of the last Japanese pioneer historic places in Orange County and a rare historic property for California,” Rick Noguchi, chief operating officer of the museum wrote in a letter dated Jan. 30, 2018, to the City of Huntington Beach. “Please don’t allow this property to be transformed into a commercial venture that disrespects important history that should be preserved for generations to come.”

Masuda agreed.

“It’s one of those things, that if it’s torn down and something else is built there,” he said, “then 20, 25 years from now—it always happens—people will say, ‘Why didn’t someone do something about it back then? You knew it was there, but you didn’t do anything.’”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.