Even fifty years later, Todd Endo remembers clearly what he heard yelled from the sidelines as he marched in the mostly-black crowd in Selma, Alabama.

"It was the only time I heard something [like that] there," said Endo, 74. "'Oh wow, even the Japs are here.'"

To a Japanese American, it was as derogatory as the "N" word. To Endo, who says he's always seen himself as "non-White in White America," hearing the epithet was an affirmation of his choice to join the march.

As the country marks 50 years since the historic 1965 voting rights marches from Selma to Montgomery with everything from individual memories to big-screen memorials, the stories of Asian-American participants, like Endo, are often lost in the mix, as are the motivations behind their solidarity.

Endo was 24-years old in 1965. Until then, everything he knew about the American South, he learned as an infant. The first three years of his life were spent behind razor wire with his family, incarcerated by the U.S. government in a World War II internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas.

The story of Asian America to that point had been forged through long stretches of discrimination. From the Chinese Exclusion Act to laws banning intermarriage, Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino and Japanese descent knew all too well what institutionalized oppression felt like.

But during Selma, the Asian-American population was little more than .5 percent of the U.S population. Later in 1965, President Johnson would sign the Immigration and Nationality Act that would massively expand immigration, particularly from Asian countries.

Those changes wouldn’t happen overnight — and certainly not in the Deep South.

From 'Bloody Sunday' to 'Turnaround Tuesday'

As a graduate student and a community church organizer in the Boston area, Endo watched the events of "Bloody Sunday" on the TV news. The violence at the march in response to state troopers killing Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 26-year-old church deacon, held Endo's attention. He watched the horrific scenes from afar, mortified and saddened.

Two days later, on March 9th, came what became known as "Turnaround Tuesday," when 2,000 marchers went to the Edmund Pettus bridge, stopped, prayed, and returned to Selma. That same day, an acquaintance of Endo's - Jim Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Boston - was attacked by white segregationists, and killed.

“When Jim Reeb was mortally wounded and his story hit the newswires, I stopped and thought seriously for the first time why Jim decided to go and I did not,” Endo recalled. “Pretty quickly, I decided to join a group that was heading to Selma, and surely the reason was that a person I knew had chosen to go to Selma to march for voting rights, and had died for that decision and cause.”

“Such is the lottery nature of injury and death…That could have been me.”

Endo headed south. When he arrived, the longer marches had been banned until there could be an assurance of some federal protection. Still, it was far from quiet in Selma. There were daily rallies and marches through town, from Brown’s Chapel a few blocks toward the court house.

“I could see Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies whom I knew from television, we knew their reputation and that they had arrested and beaten people like ourselves,” said Endo. “There was a high degree of tension and uncertainty about what could happen."

But instead of fear, Endo said he felt emboldened by “being part of something bigger than yourself.”

“I don’t remember being scared,” he said. “Could be the grandiosity of youth, or that I was surrounded by like-minded people.”

Before what would become the largest march from Selma to Montgomery later that month, much of the movement's focus was on the activity at the Brown’s Chapel worship service and rallies, where Endo spent much of his time.

“They were my ideal combination of religion and politics,” Endo said. ”I’d never been in a black church service and it certainly was boisterous—both religious hymns and the political songs. The community rallying and team building was extraordinary…I remember songs like 'Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn me Round, and 'We Shall Overcome.'"

Endo sat in the pews and took in speakers like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference's James Bevel, played in the movie “Selma,” by the rapper Common.

“He was a flamboyant guy,” Endo said of Bevel. “I don’t remember what he said, but how he said it. It was quite a performance.”

Endo joined in the planning with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) led by John Lewis, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by Martin Luther King, Jr.

“People would have marched under anybody’s leadership,” recalled Endo. “It was the group doing the real dangerous work, knocking on doors in the country where anything could happen.”

But it wasn’t King or Lewis or Bevel from whom Endo derived strength during the protests.

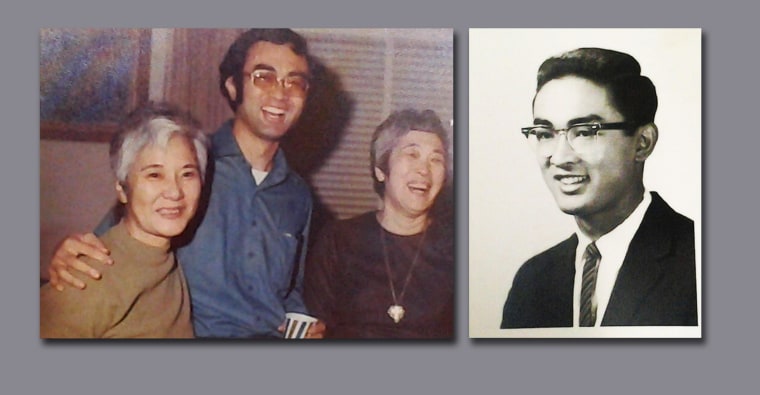

“The real heroes of the marches were people like the two female residents who marched with me,” said Endo. All these years later, he fails to recall their names. But he remembers their faces, their spirit, and their stories.

“One was a younger woman who had tried to register to vote dozens of times, had always been rejected, and vowed to keep trying to register to vote until she won," Endo said. “The other was an older woman, who had been on lots of marches, was tear-gassed on Bloody Sunday, and also vowed to keep on marching until they won. They said, ‘Never give up.’”

“If we ever feel that we’ve achieved the dream, then the dream wasn’t big enough.”

“These women were heroes to me because they lived in Selma, while I went back to Massachusetts,” he said. “I was safe. They were subject to retaliation.”

After March 17, the day President Johnson submitted voting rights legislation to Congress, Endo returned to his graduate studies at Harvard. But the ripples from Selma continued. On March 25, a white activist from Michigan named Viola Liuzzo was shot and killed by four Klansman. The news still touches Endo to this day.

“Liuzzo was shot and killed while taking marchers like me from Selma to the Montgomery airport,” Endo said. “Such is the lottery nature of injury and death…That could have been me.”

Return to Selma

Endo's survivor's guilt haunts him to this day. Yet he's determined to return to Selma for the events commemorating the 50th anniversary in March. He's still not sure, he says, how he'll feel once there.

He's already relived the March on Washington’s 50th anniversary in 2013, remembering what it was like to hear Dr. King deliver the words, "I have a dream" firsthand. But Endo knows this anniversary will be difference. The events in Selma, he says, changed his life.

“The Selma marches were more tense and purposeful than the March on Washington for me,” Endo said. ”Selma altered how I approach life. I wanted to be an actor in social and political change rather than an observer and detached analyst.”

As a young man leaving Selma, Endo also left behind his dream of becoming a college history professor. He re-focused his career on reforming education, desegregating schools and teaching disadvantaged students in the D.C. area. He later worked as an organizer in immigrant communities in Arlington, Virginia.

He's hoping his next time in Selma will once again charge his life with purpose. Endo notes the lingering racial inequalities in America, and the work that remains to be done.

“In my 70’s, I’m still looking forward to using my talents in pursuit of the same justice issues I pursued in my 20s,” Endo said. “If we ever feel that we’ve achieved the dream, then the dream wasn’t big enough.”

For more on this story, and others like it, follow @NBCAsianAmerica on Twitter and like NBC Asian America on Facebook.