Chinese-American history was rarely discussed in school when I grew up in New York City. I remember Chinese laborers were briefly mentioned during a lesson on the California Gold Rush and the transcontinental railroad. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act — America’s first immigration restriction law — was just another historical event in a string of many I memorized for tests.

My own education on Asian-American history came in bits and pieces, first via short stories my mother told me about my grandfather, who traveled through Ellis Island, and her own experience moving from Hong Kong to New York as a child, later working in the family’s hand laundry store in the Bronx.

But now our story — my family's story — is on display for everyone to see. The details of our three generations in America reduced to paragraphs of text and framed family photos. The artifacts of our lives neatly presented in glass cases.

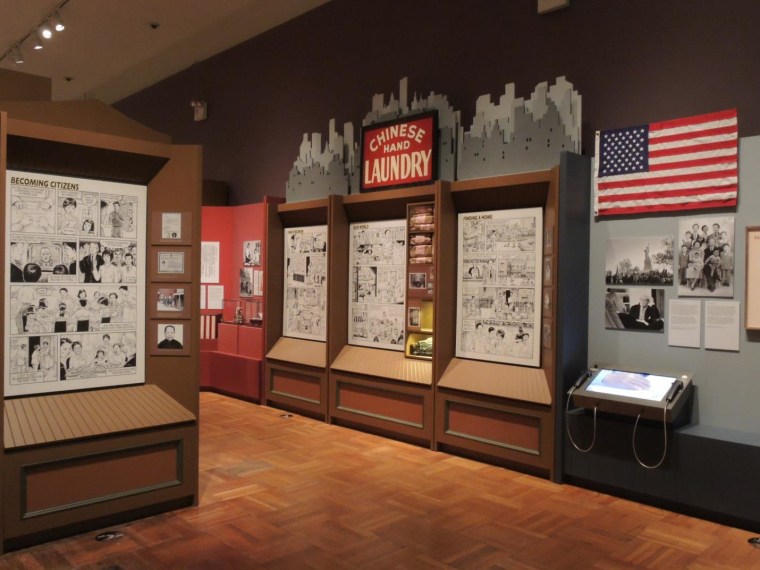

My aunt, Amy Chin, shared our history — these artifacts, photographs, and government documents — with the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. My family’s multi-generational story — told through 12 graphic novel panels spanning nearly a century — is now part of the museum’s new exhibit, Chinese American Exclusion/Inclusion, which chronicles the history of the Chinese in America from the early days of trading in 1783 to the present.

It is strange to think that my working-class family could be of interest to other people. It is even stranger to walk around a museum and see photographs and images of my relatives on the walls. I nearly cried when I went through the gallery and saw pictures of my loved ones, some living, many dead. Some images were familiar — portraits of my grandparents, mother, aunts and uncle taken in the Bronx, the painted wood sign from my grandfather’s laundry store.

Once-ordinary objects took on new meaning in their public context. My grandfather’s wedding photograph – restaged in Western clothes — was used to show immigration officials proof of marriage. A beaten-up brown suitcase most families would have thrown away became important symbolically; my great-uncle used it to make the trip to New York City with my grandfather — the literal immigrant baggage.

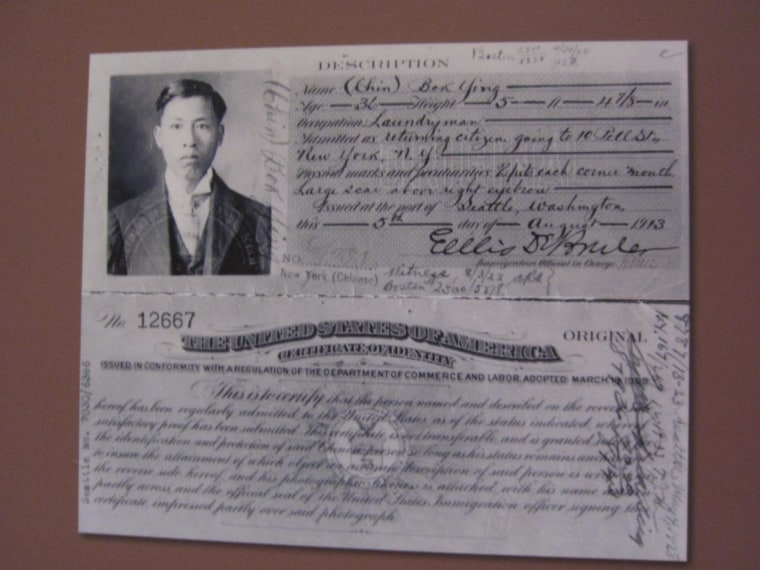

Other artifacts were new to me, like the 1913 photograph of my great-grandfather Bok Ying Chin and a copy of his certificate of identity, a document every Chinese and Chinese-American person was required to carry at all times to show they belonged in America. One panel focused on my great-uncle Pang Yee Chin, who joined the U.S. Army during World War II and died a young man in 1944 while serving in Africa. The contents of his wallet were enclosed in a glass case: photographs of himself and others, a 10 lire note and his metal identification tag.

As I wander through the collection, I’m struck by the exhibit’s breadth and depth. My family is not alone. The New-York Historical Society’s physical exhibit, accompanying website, and book delves deep into the Chinese-American experience and the relationship between the Chinese and Americans, which started even before the founding of the United States.

It is uncomfortable to see my entire family on public display — the good and the bad along with the happiness, hardships, and heartache they lived through as they carved out a life in New York City.

We’ve all studied the Boston Tea Party, but how many of us ever thought about who made the tea American revolutionaries dumped into Boston Harbor? (The Chinese did). We've studied the first-wave Chinese immigrants' work in the mines and on the railroads, but what about their contributions to farming, fishing, and manufacturing? Why haven't I learned before about The Chinese Education Mission — the first "study abroad program” — which brought 120 Chinese boys to live and study in New England during the late 1870s?

As I walk, I learn about my family. And I learn about the many others like us — some of the estimated four million people who identified as Chinese or Taiwanese in the 2010 U.S. Census. Descendants of those who first fought for Chinese inclusion in America.

I learn about Wong Kim Ark, a cook whose 1898 U.S. Supreme Court case established the law that everyone born in America is a U.S. citizen. I learn what the early Chinese migrants, similar to my grandparents, might have seen and felt as I walk through a re-creation of the Angel Island Immigration Station — the “Ellis Island of the West.”

Days after first taking it in, I am still processing my feelings from the exhibit. It is uncomfortable to see my entire family on public display — the good and the bad along with the happiness, hardships, and heartache they lived through as they carved out a life in New York City. They ran a business. They lost a relative to war. They were separated for decades because of immigration restrictions and eventually reunited. These were once our private memories, now splashed across public halls.

"This exhibit, to me, is a validation that our stories are worth sharing and knowing."

Yet I'm proud to be able to look at the exhibit as another way of tracing my family's roots and their journey to America. Not everyone can do that. Families become disconnected because of the journey. Narratives are lost over generations due to distance, deaths, or the passage of time.

My own mother, my first storyteller, died seven years ago. She did not know this exhibit would one day come. She did not know the stories she told me would be presented this way, or shared with anyone beyond our family. She would have appreciated the exhibit, but been mortified by the attention.

As I walk the exhibit halls, I feel her there with me. I sense my family — the ones that came and left before me, the ones I never even met — all around me. The photos and stories and pieces of life — even those not from my family — help me understand who they were. What they wanted out of life.

Chinese-American history continues to grow. It is a living, evolving tale and this exhibit, to me, is a validation that our stories are worth sharing and knowing.