Film director Lee Joon-Ik, whose movies helped launch the careers of Korean actors Jang Geun-Suk and Lee Joon-Ki, has played a pivotal role in bringing South Korean cinema to audiences worldwide. Widely known for his 2005 period film "King and the Clown," which explored LGBT themes just one year after South Korea's Youth Protection Commission removed homosexuality from a list of activities deemed socially unacceptable, Lee has established himself as a pioneer of the Korean historical drama format known as sageuk.

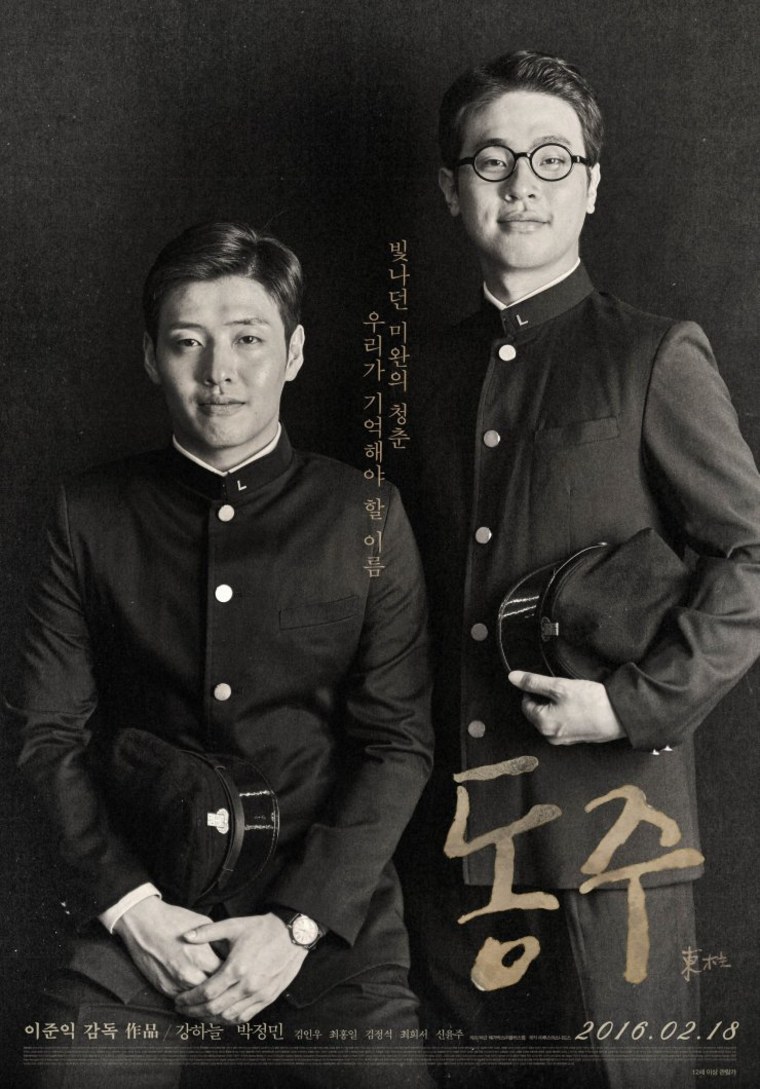

His most recent film, "Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet," marks his first foray into indie filmmaking. A collaboration with fellow Korean director and screenwriter Shin Yeon-shick, the film depicts the life and death of poet Yun Dong-Ju, who grew up during the Japanese colonial era and found prominence after his poems were published posthumously.

On Tuesday, the New York Asian Film Festival screened the film at Lincoln Center in conjunction with the Korean Cultural Center’s inaugural “Korean Movie Night New York: Master Series.” The film, shot entirely in black and white, is a stylistic contrast to Lee’s 2015 historical drama "The Throne," which will be screened at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater on Thursday as part of the New York Asian Film Festival.

NBC Asian America sat down with director Lee Joon-Ik to talk more about "Dongju" and his perspective on filmmaking and storytelling.

Your most recent film, "Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet," is your first indie film. Why did you choose to make an indie film, and are you planning to make more indie films in the future?

Every director has a desire to make an indie film — even directors like me who do mostly commercial films. When making commercial films, you have to take into account the interests of your investors and the audience as well. I think the great thing about indie films is that you can make the film that you envision without as many constraints, so you have much more creative freedom. Every commercial film director wants to make an indie film, and in my case, it’s a very fortunate thing that I was able to do it. In the future I’d like to continue making both commercial and indie films.

Any particular reason why you chose to film "Dongju" in black and white?

There are two reasons. First, the film takes place between 1935 and 1945, when all films were in black and white. Also, all of the photos of Yun Dong-Ju in Korean textbooks are in black and white, so I thought that would be a familiar image for Korean audiences. We were less burdened by commercial concerns, so I felt we could portray the era more realistically by filming the movie in black and white.

The second reason is because of budget constraints. If I’d wanted to film that period in color, the production costs would’ve been really high. And since it’s not a commercial film but a film that centers on a poet — it’s not an action blockbuster or anything — we chose to make it in black and white so we wouldn’t go bankrupt.

Why Yun Dong-Ju?

In 1999, I produced a movie called "Anarchists" that was set in the 1920s. I did a lot of research on the Japanese colonial period for that movie, and actually Yun Dong-Ju didn’t capture my interest then. But in recent times, there’s been a lot of tension between Korea and Japan over historical and political issues — for example, the comfort women issue or Obama’s visit to Hiroshima to honor the Japanese victims of WWII. Many Asians see Japan as having been the aggressor in Asia before it became a victim of the atomic bomb. They want to see Japan acknowledge their previous crimes, but the Japanese government constantly denies any wrongdoing. So my question was, how do we work this out?

I thought meeting violence with violence was not the answer — rather, someone who could protest through non-violent means, like Yun Dong-Ju, was the answer to our times. Yun Dong-Ju wasn’t just a Korean — he was actually born in China, was ethnically Korean and spoke Korean, but died as a Japanese because he had to adopt a Japanese name. So I see him as a more global citizen. Just as Gandhi used non-violence to protest against English colonialism, Yun Dong-Ju also used non-violent means — specifically poetry — to protest against the violent actions of the Japanese empire. And in today’s world, we need people like Yun Dong-Ju.

Is "Dongju" banned in Japan?

Nope, it’s going to premiere in Japan in December 2016. I’ll also be giving a seminar at Rikkyo University in Japan around then. Yun Dong-Ju attended Rikkyo University, so I’ll be screening my film there and having a discussion with the students afterwards.

Actually, there are many avid readers of Yun’s poetry in Japan. They admire his poems and his spirit. For decades, groups of them have been gathering together every year on the anniversary of his death to recite his poems. There are many Japanese people who acknowledge what Japan has done in the past and who sympathize with what Koreans and other oppressed people had to go through.

RELATED: Asian American Film Festival Focuses on Content to Rebuild

Let me be clear that it’s definitely not the Japanese people I have a problem with — it’s Japan’s previous militarism, and the Japanese government’s constant denial of war crimes. Germany, in contrast, has acknowledged and expressed remorse over its war crimes, including the Holocaust, for the past 70 years. I made this film because for the past 70 years, the Japanese government still has not acknowledged the wrongs that they’ve committed. I tried to stick very closely to the facts, and I chose Yun Dong-Ju partly in order to show the Japanese audience that he wasn’t some gun-toting terrorist, but a poet who studied at a Japanese university and ultimately died in a Japanese prison.

Do you direct your films with an international audience in mind, and if so, since when have you started doing this? What do you hope people will get out of your films?

For me, the purpose of film is to uncover the truth through fiction. There’s a distinction to be made between mere facts and the truth. I believe that facts are not always the truth, because the facts that we see in books and other sources are often controlled or manipulated by those in power. I make historical films, so I research a lot of material, but I don’t believe everything I see or read. I always make sure to check the facts that have been recorded. Many of my projects are based on facts, but I try to arrive at the truth via a fictionalized narrative, and I hope that through my movies, I’m able to communicate the truth to my audience.

Sure, I do have a desire to help inform foreign audiences about Korea’s culture and history through my movies, but it doesn’t influence the way I make them. If I were to cater my films to an international audience, they would be heavily repackaged and embellished, and in that case I would be nowhere near the truth. I think it’s best to create films without being too concerned about international audiences.

Why did you become a filmmaker? What got you interested in filmmaking?

I never planned to be a movie director. I needed to make a living, so I ended up becoming a film director. Film is basically a tool for me — a medium that has the potential to tell all the stories of the world. I never make a film just for the sake of making a film.

Why have you chosen to specialize in the Korean historical film format?

I learned a lot about Western history when I was growing up. I used to be involved in a lot of foreign content licensing deals in the 1990s and early 2000s, and I realized many of my Western counterparts couldn’t tell if a movie was Chinese, Korean, or Japanese, particularly when it was a historical film. And that made me angry.

I thought, “Korean history is much longer than yours. Korea has experienced so many more incidents than your country has. Korean philosophy is so much richer and more diverse than you would’ve ever imagined.” And I decided to show all of this through my films. So that’s why I created movies like "King and the Clown" and "The Throne" — to show that there are other great sad stories out there besides your Greek or Shakespearean tragedies.

Do you plan to continue focusing on the Korean historical film format in the future? Any projects that you’re currently working on or will be working on in the near future that you can tell us about?

I do plan to continue making more historical films in the future, but right now I’m working on creating a science fiction film. But in a way, it’s the same as making a historical piece because you’re not dealing with the present. Sci-fi and historical films don’t involve our current reality, so both can be considered as fantasy, in a sense.

In 2011, after your movie "Battlefield Heroes" did not achieve as much box office success as you’d anticipated, you announced your retirement. Why did you retire, and what made you come out of your retirement?

[In English] Talking mistake! (Laughs).

[In Korean] I was at an event for "Battlefield Heroes," and there were probably about 80 reporters there. There wasn’t much to talk about, so I jokingly said, “If this movie doesn’t do well, I’ll retire!” But then the reporters took my words seriously and uploaded my statement immediately on the internet. So basically I was forced to retire (laughs). I really had no desire to retire from filmmaking.

[Jokes in English] I’m a liar.

Who are some of the directors who have influenced you?

Akira Kurosawa and Stanley Kubrick. Stanley made films that were so original they had no precedent. Kurosawa had a certain style of creating epic cinema, and watching his films helped me a lot when I was creating my own period pieces. In the case of "Once Upon a Time in a Battlefield," I was influenced by "Monty Python" and the "Holy Grail," "Life of Brian," and "The Meaning of Life." "King and the Clown" was influenced in part by Shakespeare. "The Throne" was influenced by Greek tragedies like "Antigone."

This interview was translated from Korean and has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.