Ellison Onizuka was a local boy who made it to space.

Born in the community of Kealakekua in rural Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii, Onizuka grew up playing among coffee plants and as a member of the Boy Scouts and the FFA.

He would eventually leave Hawaii for the mainland, and on Jan. 24, 1985, he became the first Asian-American, the first Japanese-American, and the first Hawaiian in space as an astronaut on the space shuttle Discovery.

But even orbiting 212 miles above the earth's surface, the islands never left him — he brought them up there in the form of freeze-dried Kona coffee.

A year later, on the particularly cold morning of Jan. 28, 1986, Onizuka embarked on his second spaceflight, except this time, he didn’t return. Seventy-three seconds after lifting off, the space shuttle Challenger broke apart after o-rings in the right rocket booster failed to seal in super-heated gasses.

Onizuka, as well as the six other astronauts on board, were lost. He was 39.

Hard Work and Determination

"I feel privileged to have been on a crew he was on because he was fun to fly with. Saying someone was fun to fly with says it all. He added an entire dimension of enjoyment to an event that's already a big part of your life."

For those who knew him while he was an astronaut, two things about Onizuka are as clear now as they were two and a half decades ago. One: he loved his family — his wife, their two daughters, and both of their extended families back on the islands; and two: that he was a hard worker.

Onizuka was driven by a work ethic instilled in him by his parents and his desire for himself and the people around him to accomplish as much as they could, his friends say. That drive took him from the Big Island to the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering in June 1969, and a master’s in that same subject in December of that same year. In January of 1970, he entered active duty with the Air Force after finishing four years in the ROTC program at Boulder.

“He got his drive to succeed from his parents,” James Buchli, a retired astronaut who joined NASA as part of the same 1978 astronaut group as Onizuka, told NBC News. Buchli also flew with Onizuka on his first mission and trained with him for months to prepare.

“They were very interested in all of their children — but especially Ellison — in succeeding in school and as adults,” Buchli said. “Ellison went all the way from Hawaii to Colorado for college, and that couldn’t have been easy, but his folks insisted that he get his education. They used to say ‘We can’t give you money, but we can give you an education.’”

As a member of the Air Force, Onizuka was a flight test engineer and trained at the Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California, working on numerous experimental military aircraft. In 1978, he was selected to be an astronaut, part of the first new group of astronauts to be selected in nearly a decade. He would be selected for his first mission — a secretive space flight to launch a payload from the Department of Defense — seven years later.

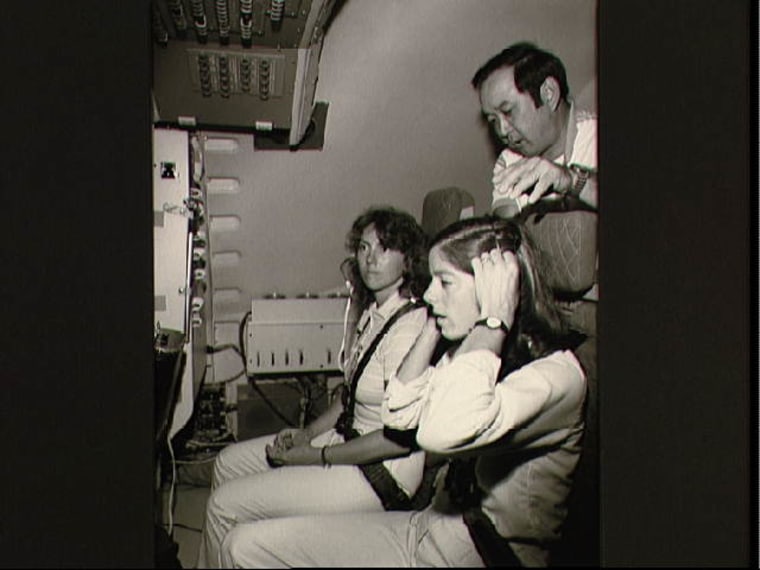

“When we were assigned down to Houston — and eventually to the same crew — we began to do training sessions together,” Loren J. Shriver, a retired astronaut and pilot of the mission, told NBC News. “Sometimes they’d be an hour, sometimes three, four, maybe even five. Ellison was a very hard worker. He had great attention to detail, and he wanted to do the right thing for everyone he came in contact with. He was always interested in making sure we all did our best.”

But as hard of a worker as he was, Onizuka had a lighter side that was always easy to find. He was easygoing, and made a conscious effort to personally connect with the people around him and put them at ease.

“Sometimes my North Dakota humor and his Hawaii humor didn’t understand each other, but we used to joke back and forth quite a bit,” Buchli said. “When you hit it off well and you work well with people, it made going into space a whole lot more rewarding. I feel privileged to have been on a crew he was on because he was fun to fly with. Saying someone was fun to fly with says it all. He added an entire dimension of enjoyment to an event that’s already a big part of your life.”

His island upbringing stayed with him in Houston. In addition to the Kona coffee he gave to mission control before his first flight and brought with him into space, he, Buchli, and other astronauts would go fishing at nearby Galveston Bay, catching speckled trout. He became known for hosting luaus, complete with full hogs cooked overnight buried in his backyard.

“Burying the pig in the back yard and cooking it all night was a very big event.” Buchli said. “He was good at it. It’s quite a feat, and he was a champ. He knew how to do it well.”

“I used to kid him somewhat whenever, I got a piece of the pig,” Buchli continued, chuckling. “I’d say ‘This looks like the nose, can I get another piece?’”

That personality was evident even in training. During serious or grim moments with his crew members stressed, Onizuka made sure the people around him kept perspective.

“Ellison had a great sense of humor,” Shriver said. “He and Jim Buchli would play little practical jokes now and then to get us to relax a bit.”

“We were doing simulations of engine-out aborts,” Buchli said. “Most of those wound up in what we called the ‘black zone’ — the area where survivability is very sketchy. We were doing those and just about every one of them, we ended up in the Atlantic Ocean.”

“The next time we had that simulation, Ellison and I showed up with scuba masks and a set of fins,” Buchli continued. “You keep things in perspective, and when you can, you keep your training even keel with some humor.”

Teaching in Memory

"I always think of El. He probably didn’t think of himself as a pioneer, but somebody had to be the first, and I’m glad it was him.”

Onizuka’s death at 39 was a loss for many: Hawaii lost one of its favorite sons, the Japanese-American community lost a role model, and his friends and family lost a caring individual. To keep his memory alive, they banded together to build monuments and host events in his name.

In Ukiha, Japan, Onizuka’s grandparents’ hometown, there stands an Ellison Onizuka Bridge. In Hawaii, a visitor’s center on Mauna Kea bears his name. Two astronomical features, an asteroid and a crater on the moon, are also named named for him, as well as multiple streets, including one in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, which also hosts a memorial to the Challenger — a scale model of the shuttle.

And each year, two educational events are held in his memory, one at El Camino College in California and one at the University of Hawaii at Hilo.

“We’d like to grow the education aspect and do more,” Tim Stowe, current president of the Foundation for Ellison S. Onizuka, told NBC News. The organization plans the Onizuka Space Science Day in California, which attracts over 1,000 students annually, for a day of space science-related activities and lectures. Each year, the event hosts an astronaut, who visits schools in the area the day before.

“From what I know about him from his brother and wife, he really liked to be a role model to kids, to be an example of what you can achieve with a lot of work and frankly a good bit of luck,” Daniel Tani, a retired Japanese-American astronaut, told NBC News.

Tani was just working his first job out of graduate school when the Challenger was lost, and was involved in the Los Angeles Japanese community, which had embraced Onizuka. He became an astronaut and met Lorna, Ellison Onizuka’s wife by chance at a convention. Lorna Onizuka had stayed active in the space community after her husbands death as a consultant for JAXA, the Japanese space agency. Shortly after he became an astronaut, Tani volunteered to speak at the Onizuka Space Science Day and eventually joined the planning committee for the event.

“[Onizuka] was big on education and excelling to the best of your abilities,” Shriver said. “It was important to him to prepare yourself to do the best in whatever field you choose and not put limitations on yourself. He himself was a testimony of that.”

Even after his passing, Onizuka has left an impact on people — from current, retired, and future astronauts, to students and educators. American international travelers also carry a piece of Onizuka's memory with them: a quote from him appears on the final page of each U.S. passport.

“Every generation has the obligation to free men’s minds for a look at new worlds … to look out from a higher plateau than the last generation,” it reads.

“Being the first Asian American, Japanese American, to be selected, I don’t think it’s a barrier that he recognized that he was breaking,” Tani said. “But he represents the widening of the image of what an astronaut could be. He provided a great connection to Hawaii: here’s a Hawaii boy who was literally raised next to a coffee plantation. In some short years, he achieved and was very fortunate to fly in space and represent his heritage and his state.”

He added, “I always think of El. He probably didn’t think of himself as a pioneer, but somebody had to be the first, and I’m glad it was him.”