I am teaching a class at the community college right now called “Chinese Food: Culture and Customs.” It is a light, fun, field trip-based class where we visit a Chinese grocery store, eat at a Taiwanese restaurant, and talk about everything from food symbolism to Chinese table manners to how to cook rice.

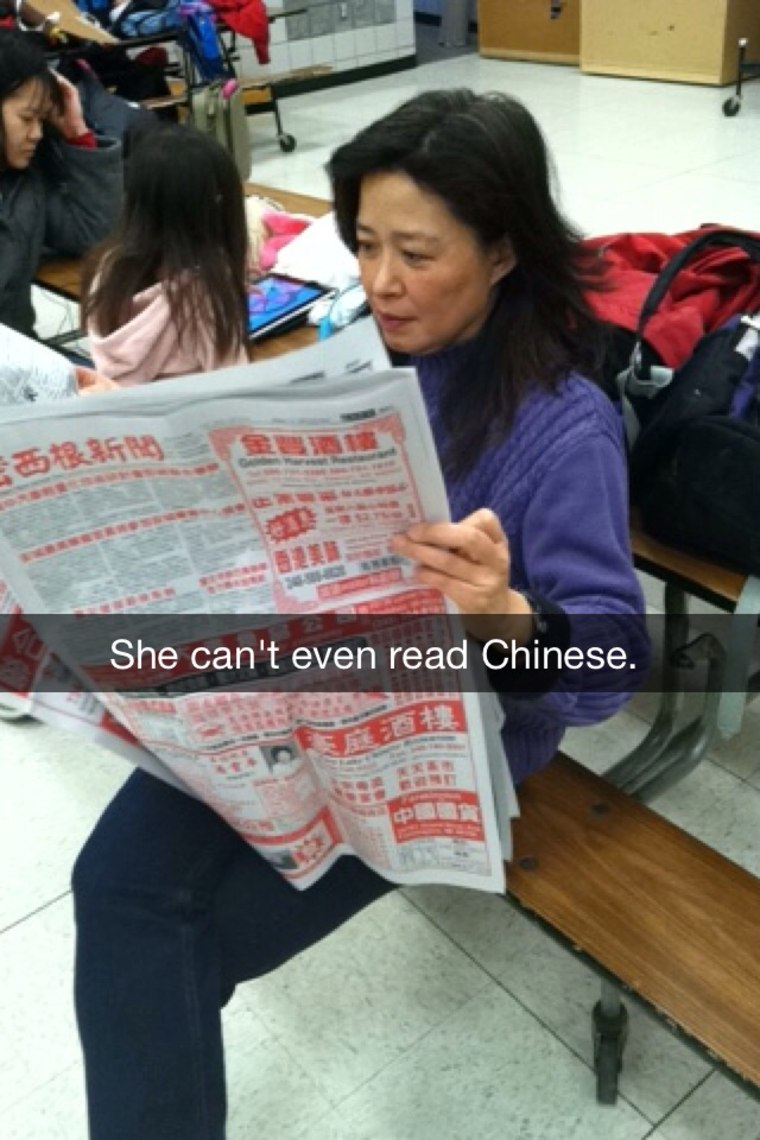

I am gripped by anxiety on the first day of class, however, when a "real" Chinese person walks in.

Why is she taking my class? What if I say something wrong? What if I am not “authentic” enough?

A Caucasian friend and a Taiwanese friend both ask, “What do you mean by a ‘real’ Chinese person?”

My Asian-American girlfriends just guffaw. They know.

The struggle.

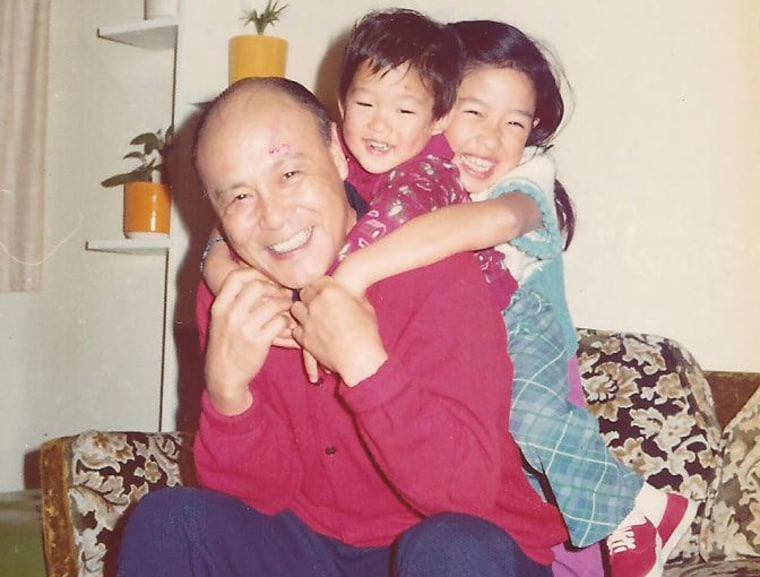

Having grown up as the child of immigrants in America, I am often aware of how much I do not know. I think that is why I am always reading instructions, hungry to know how to do things the “right” way, even to the level of “lather, rinse, repeat.” So much of what I saw on television growing up, from “Happy Days” to “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town,” felt like anthropological documentaries to me. As a teenager, I read “Dear Abby” and “Ann Landers” religiously, trying to figure out the meaning behind social interactions where the rules are not marked, the expectations unspoken.

"Although some are afraid of Muslims today because they are different, I am becoming afraid of Islamophobes because I am different. Sometimes I am actually afraid of how white people who don’t know better might mistake me and my children. Things look different from the other side of brown."

However, as much as I feel I do not know America, I certainly know China and Taiwan even less. Because I do not read Chinese very well, I am cut off from Chinese books and magazines and written instructions (not that there are many lying around). There was no Chinese television station when I was growing up. I knew only my parents’ friends and relatives, and I did not know many Chinese-American kids outside of my cousins. I know thousands of songs in English, but only a handful of Chinese children’s songs. I only know one Chinese joke (and it is not very funny unless you are five). The only Chinese swear word I know was one I learned in recent years from a Caucasian law professor. I do know how to cook Chinese food, but I learned the basics from a James Beard cookbook first, then from my mother and grandmother later.

Amongst ourselves, friends and I joke about who is “more Asian” or “a better Chinese person,” ranking ourselves on an imaginary scale of authenticity that arcs across the Pacific, even though out in the world, it is our Americanness that is questioned daily. It is our Americanness that we are asked to prove.

I am also shaped by the experience of constantly having to prove my Americanness, especially when I am “the only one” or, worse, “the other one.” I can read the hesitant pauses when people are uncertain if I speak English. I remember the 4-H leader who had always been so nice to me suddenly turn angry, her face contorted, accusing me of getting preferential treatment because of my race, when I had broken no rule. I chafe from being questioned my whole life, “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?”

I am American.

Yet, how American am I that my Americanness is so easily and so often questioned?

The morning of September 11, 2001, I received a phone call to turn on the television. It took a few minutes to figure out what I was even seeing. Then one of the World Trade Center towers collapsed before my eyes. I still did not comprehend the magnitude.

My first thought as a journalist covering Asian-American issues at the time was: “I hope Chinese people didn’t do it.”

Ashamed at my selfishness and my fear, I have never told anyone this.

I remember it now in this moment of intense anxiety, fear, Islamophobia, and #BlackLivesMatter. I am also hurt and frightened by the divisive and hate-filled rhetoric and ignorant acts aimed at Muslims and those mistaken for Muslims, and at immigrants and refugees, at so many people of color. Historically, racial intolerance has at turns been directed at Native Americans, African Americans, Irish Americans, Italian Americans, Jewish Americans, Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Hispanic Americans...

It could as easily be anyone.

Although some are afraid of Muslims today because they are different, I am becoming afraid of Islamophobes because I am different. Sometimes I am actually afraid of how white people who don’t know better might mistake me and my children.

Things look different from the other side of brown.

At the drugstore the other day, I overhear the pharmacist gradually raising her voice and repeating herself slowly, “11:15.” I look up and see an older Chinese man waving his arms widely in explanation. “Er shi fen zhong.” I walk over.

“He said, ‘20 minutes,’” I translate, not knowing what the conversation is.

Both turn to look at me.

The older Chinese man says to me in Mandarin, “Tell her I’m going to the grocery store next door and I’ll be back for my prescription in 20 minutes.”

I always step in to help when I see something like this, simply because I can — because I know that English and education are privileges that I happen to have, because my grandparents live far away and I cannot help them in their daily lives. So I try to help other people’s grandparents — sometimes with language, sometimes with culture — and I just hope that someone is out there helping my grandparents in the same way.

So although my friends and I joke about being “fake Chinese people” and fight to be accepted as “real Americans,” I speak up to remind myself of my privilege and perspective standing between and among cultures. I speak up to remind myself that all of us are different, differences are strengths, and we all have more in common than not, no matter what others might say.

As the American-born child of immigrants, that is the America and the future that I choose.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr.

IN-DEPTH