The main thing Teli Hafoka remembers about her high school experience is that she was on her own.

Born to two working-class Tongan immigrants and raised in Stockton, California, she and her four siblings were often the only Pacific Islanders in the school. Even though she played basketball and ended up in the top 10 percent of her high school class, counselors and teachers gave her little encouragement.

Some made her feel “pigeonholed as a dumb athlete,” and directed her toward community colleges. Others left her completely alone; Hafoka thinks they assumed since she was Asian, she “didn’t need any help in school,” or any information about college or scholarships. Her parents wanted her to go to college, but they didn’t know much about the process. They got overwhelmed filling out the FAFSA forms.

Hafoka didn’t take the SAT—no one told her to—and she made it one year in junior college before she dropped out. That was better than some of her siblings, who had seriously struggled in high school. One brother was in jail.

“We didn’t fit in anywhere,” she said. “The adults in our lives didn’t know what to do with us.”

Hafoka’s family’s experience mirrors the findings of two recent studies suggesting that Pacific Islander students are getting lost in the shuffle—and are falling far behind in college readiness as a result.

“It renders these communities invisible. They’re just off the radar.”

A report released by the ACT in May found that less than one in five Pacific Islanders who took the ACT met the scoring benchmarks in all four of the exam’s subject areas. Forty percent of Pacific Islanders met zero benchmarks. Meanwhile, a new report by nonprofit organization, Empowering Pacific Islander Communities, teases out some similarly dismal statistics. Only 18 percent of Pacific Islander adults have a bachelor’s degree, a rate rivaling Hispanics and African Americans. Pacific Islanders are about half as likely as the general population to hold bachelor's degrees.

There are around 1.2 million Pacific Islanders in the United States, and that number is growing rapidly: the population grew 40 percent between 2000 and 2010. Many of them live below the poverty line; there’s even evidence that Pacific Islander young men are downwardly mobile. Culturally, their families are tight, and there’s often pressure to stay at home to support the family rather than go off to college.

And yet, the challenges Pacific Islanders face are concealed by government data, which groups dozens of different ethic groups under the nebulous umbrella “Asian/Pacific Islander.” Some of this population is affluent and highly skilled, masking the issues of at-risk groups like Pacific Islanders and failing to fully represent the economic and cultural range of the Asian American experience.

Robert Teranishi, professor of education and Asian American studies at UCLA and the lead author of a 2011 study on Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and college, calls the government's data “an inaccurate portrait of an extremely diverse population.” It’s a portrait that ends up perpetuating the “model minority” myth, the prevailing assumption that Asian-Pacific Islander students are unilaterally academically successful.

“It’s like somebody just dropped me in a hole, and it was pitch-black...I didn’t know where to go ask for help."

Teranishi said “this myth is misleading and really damaging for more vulnerable sub-populations of Asian Americans,” which includes not only Pacific Islanders but Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Hmong communities, among others. “It renders these communities invisible. They’re just off the radar.”

This isolation—the kind Hafoka and her siblings say they felt—starts at the high school level and only gets worse in higher education, where Pacific Islanders are represented even less. Part of the problem, Teranishi said, is role models: Only 1.5 percent of teachers, and 0.5 percent of principals, are Asian American or Pacific Islander.

“That limits the ability of schools to understand work with the communities they serve,” Teranishi said. “I think it’s important for kids to see themselves in the adults who are in their schools. They need that element of trust.”

Pacific Islanders also struggle with a sense of place and belonging among their peers that is easier to find in certain schools with more established minority populations. Kevin Tugruwfaimaw, a student at Portland State University, said he had a rude awakening when he came from Hawaii to the mainland freshman year.

“It’s like somebody just dropped me in a hole, and it was pitch-black,” said Tugruwfaimaw, who’s originally from the island of Yap. “I didn’t know where to go ask for help. Hispanic and Black students had special counselors, their own academics departments. They had special places for them to live. We don’t have that.”

In many other ways, though, the Pacific Islander experience parallels that of low-income African Americans or Latinos. Sefa Aina, director of the Asian American Resource Center at Pomona College, said authority figures often track Pacific Islander students into easier classes, tap them to play sports instead of join the math club, or assume they’re gangsters. But Pacific Islander youth also grapple with the opposite problem: their teachers may presume a struggling kid is thriving simply because he or she is Asian.

"Hispanic and Black students had special counselors, their own academics departments. They had special places for them to live. We don’t have that.”

“Teachers and counselors are either going to have raised expectations or lowered expectations,” Aina said. “Either way, their perceptions are often skewed.”

These muddled assumptions extend to the scholarships available for Pacific Islander students—or the lack thereof. With federally funded scholarship programs, like TRIO, created to assist students from disadvantaged backgrounds, it’s often left up to the individual chapter to decide whether Asians will be included. There are a few dedicated funds available—like the Asian Pacific Islander American Scholarship Fund (APIASF)—but college counselors often don’t know about them.

Reyna Ta’amu, a recent graduate of Whitney High School in Cerritos, Calif., found out about APIASF not through school, but by Googling.

“You don’t really come across a lot of organizations for Pacific Islanders, so when I found [the scholarship], I was skeptical if I should even try,” said Ta’amu, who is Samoan. “I didn’t know if it was sketchy. My mom was like, ‘Hmm, I haven’t heard anything about it.’”

Ta’amu ended up winning a scholarship, but most of her peers never get the chance. Many are informed by scholarship officials that Asian Americans aren’t underrepresented, and therefore nor are Pacific Islanders. Meanwhile, the few scholarships that do exist are overwhelmed with requests.

Troy Keali’I Lau, a native Hawaiian and doctoral student at UCLA who has worked with Aina, has applied to a number of need-based scholarships with no luck. Many of his peers are in the same position.

“I think there’s plenty of [Pacific Islander] students applying for scholarships,” he said. “We’re just not getting them. And I don’t think we should have to have Pacific Islander-specific scholarships. The mission statements [of the larger funds] have to be realigned so that we’re looking at need-based individuals.”

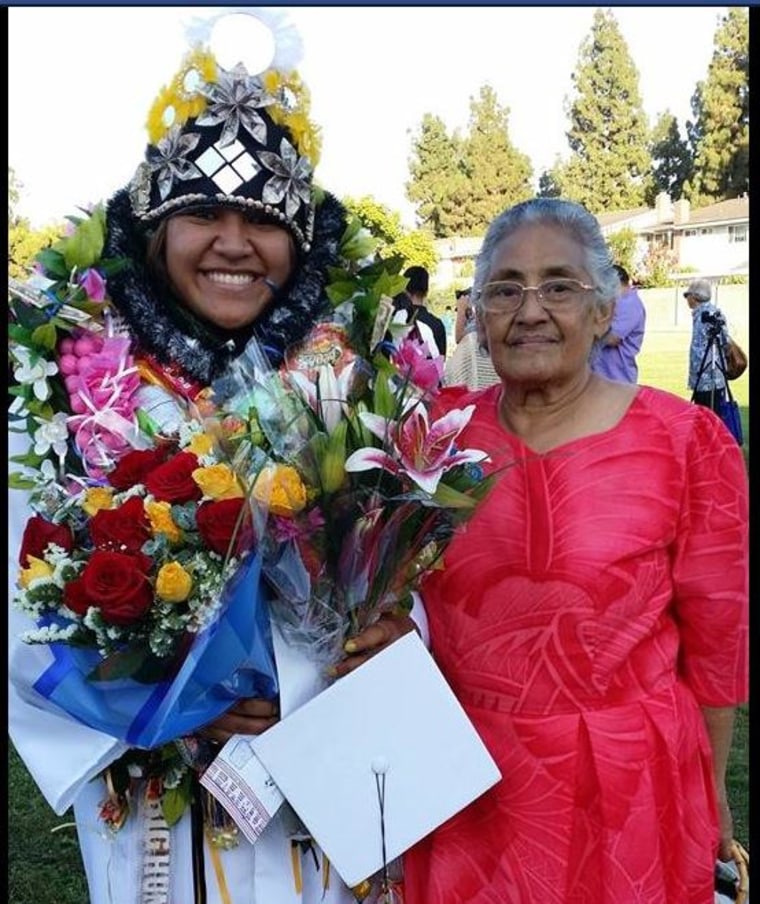

In the meantime, Keali’i Lau and Aina try to provide the mentorship they didn’t have, through programs like the Saturday Tongan Education Program (STEP), which leads tutoring programs in Pomona-area high schools every Saturday. Hafoka, now 32, tries to close the isolation gap, too. She eventually decided to go back to college in 2008, this time to the University of California-Riverside, and joined the Pacific Islander Student Alliance. One day, she and some PISA members ran into a few Polynesian high schoolers at a local McDonald’s and struck up a conversation. Hafoka and her friends started tutoring and leadership programs, and later a Pacific Islander history series, “because [the kids] complained they never saw themselves in history class.”

Sometimes, PISA would invite the high school kids to go on a campus tour. Hafoka would help rally all the Pacific Islanders on campus for the occasion.

“We were all there to greet them,” she said. “It was just to say, ‘There are people like you here.’”