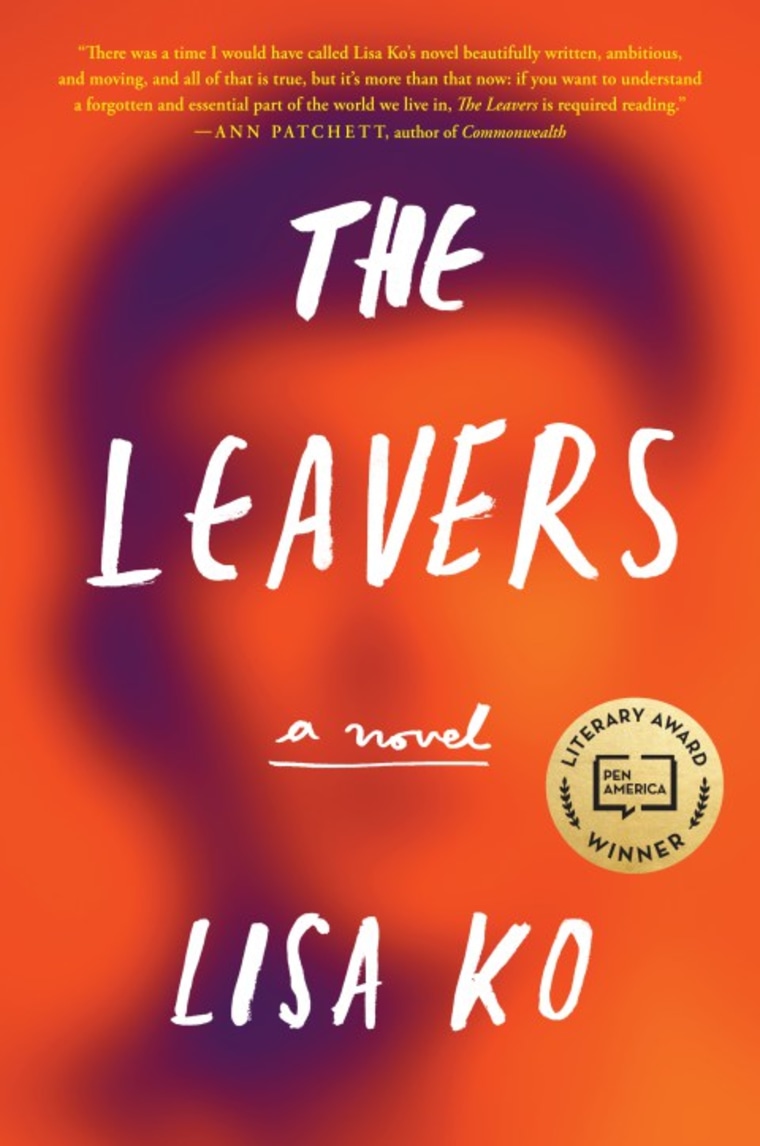

If Lisa Ko hadn’t set out to lose, she wouldn’t have won a prestigious literary prize, leading to the publication of her debut novel, “The Leavers,” on May 2.

The Brooklyn-based writer had set a goal in 2014 to get 50 rejections a year, she told NBC News. The idea was that the more she put herself out there, the more chances she had of getting her work accepted. It was nearing the end of 2015, and she needed to bump up her rejection numbers. She had been working on a novel for years. It wasn’t quite ready, but on a whim, she sent it to a competition.

“Whatever, I’ll never win. But I’ll get another rejection,” Ko said of what she was thinking at the time.

“I was always really conscious of being different on the outside, but I think there was a way that I was able to use that to my advantage in terms of being creative and having fun with it.”

Months later, when the author Barbara Kingsolver called Ko to tell her that she had had won the 2016 PEN/Bellweather Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction, Ko didn’t get the message at first. She was vacationing in the Bahamas without cell phone reception and then accidently left her phone behind. She returned to New York City to find that Kingsolver had been trying to reach her all week. The $25,000 prize is awarded biennially to the author of a previously unpublished novel. It also comes with a book contract.

“I was in disbelief. My first reaction was maybe she was calling all the people who had lost to tell them they lost," Ko said. "I was super jetlagged and out of it. It didn’t really sink in 'til the next day.”

Ko, 41, started writing “The Leavers” in the fall of 2009 after she read a story in the New York Times about the detention of Xiu Ping Jiang. Jiang, an undocumented immigrant, had been arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement as she traveled from New York to Florida to start a job at a Chinese restaurant.

Deemed a suicide risk, she was kept in detention, often in solitary confinement, for over a year, the Times reported. Her mental state deteriorated. She had tried to bring one of her sons to the United States, but he was caught in Canada, placed in the foster care system, and eventually adopted. Ko also read about other cases where parents had been deported but were not allowed to take their U.S.-born children with them.

“I just wondered what it said about us as a country and what it says about how Americans view immigrant bodies. Like the idea that these immigrant parents could be deported or seen as unassimilable while the children had to stay,” Ko said.

“The Leavers” tells the story of Polly, an undocumented Chinese immigrant, who goes to work one day and never comes home. Calls to her phone go unanswered, and no one knows what happened to her.

Her 11-year-old son Deming is soon adopted by a well-intentioned white family who rename him Daniel. The new parents try to give him an all-American upbringing, but the boy is haunted by his mother’s disappearance. When he is older, he goes looking for her.

Ko grew up in a New Jersey suburban town that was overwhelmingly white, an upbringing that informed her character Daniel, she said.

“I was always really conscious of being different on the outside, but I think there was a way that I was able to use that to my advantage in terms of being creative and having fun with it,” Ko said. “It really formed a lot of my early identity and also who I wanted to write about and who I wanted to center in my work.”

Much of the emotion around Daniel’s experiences growing up Asian in a white town came from Ko’s own memories.

As a five-year-old, Ko started writing stories and keeping a journal. The only child of Chinese immigrants from the Philippines, she was the first in her extended family to be born in the United States.

“I was always really aware that my family’s history ended with me ’cause I was the only grandchild on one side,” Ko said. “So there was a lot of anxiety about being the receptacle of all of my family’s story and not wanting to forget from a very young age.”

“I was in disbelief. My first reaction was maybe she was calling all the people who had lost to tell them they lost. I was super jetlagged and out of it. It didn’t really sink in 'til the next day.”

Ko didn’t show anyone the stories she wrote until high school, when supportive teachers encouraged her. At Wesleyan University, she majored in English and took writing workshops but found them discouraging. She credits spaces specifically for writers of color, like the Asian American Writers Workshop — where she was an intern one summer — and the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation, for giving her role models and a writing community.

With other writers of color, Ko said, “you don’t have to necessarily explain your characters. … People aren’t going to question, ‘I don’t believe racism happens to Asian Americans.’”

It took eight-and-a-half years for Ko to write and edit her book. Meanwhile, she juggled all kinds of jobs, from freelancing as an editor to adjunct teaching and full-time office work, writing when she could. Her persistence has paid off. The book launches in Manhattan on May 2, followed by a national book tour in May and June.

“It takes a lot of extreme stubbornness and failure,” she said. “Like failing over and over again and getting rejected over and over again, and still really believing in the work and wanting to get it done more than wanting to give up.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.