On a blustery Friday afternoon in early February, New York City Council Member Margaret Chin was seated at the head of a conference table in her cramped Chinatown district office, quietly listening as a handful of Mandarin-speaking men presented a stack of summonses.

The visitors, a group of commuter-van drivers and operators, were there because they couldn’t understand why they had been ticketed for operating their shuttles between Chinatown and Flushing, a Queens community that is also home to many Chinese.

As the meeting wrapped up, a staffer emerged from the glass-partitioned conference room to make photocopies of the summonses. The men exited. The councilmember let out a long sigh.

“I don’t know,” she said to several staffers nearby. “We have to get to the bottom of what’s going on.”

Chin, 61, has spent much of her adult life getting to the bottom of things in Manhattan’s Chinatown, the neighborhood where she grew up and where she has served in public service for decades. Her plain talk on education, affordable housing and quality-of-life issues earned her the support of many Lower Manhattan residents, who sent her to the City Council in 2009, and again in 2013.

But at times her views have also put her at odds with some Chinatown residents and Chinese Americans - most recently when she called for the indictment of a Chinese-American police officer accused of fatally shooting an unarmed black man.

“I’ve learned that I cannot make everybody happy,” Chin told NBC News. “But I have to stick to my principles, in what I believe in.”

Chin's father, who left the mainland for Hong Kong in 1950 with his wife and Chin's older brother - tried for years to get his family to America, including getting his children baptized as Catholics.

“He thought that the church would help us get to the United States,” she said. “That didn’t happen.”

Chin's father made his way to New York without documents via Colombia, South America in the 1960's - where he had gotten a job and learned Spanish. Soon after his U.S. arrival, Chin's uncle in Boston, who'd sponsored his brother's visa, received a call that the government was processing his case.

“My father had to make a decision - to go back and bring the whole family here, or to stay here without documents,” she said. He returned to Hong Kong, raised money from family, bought airline tickets for his wife and five children, and came back to America.

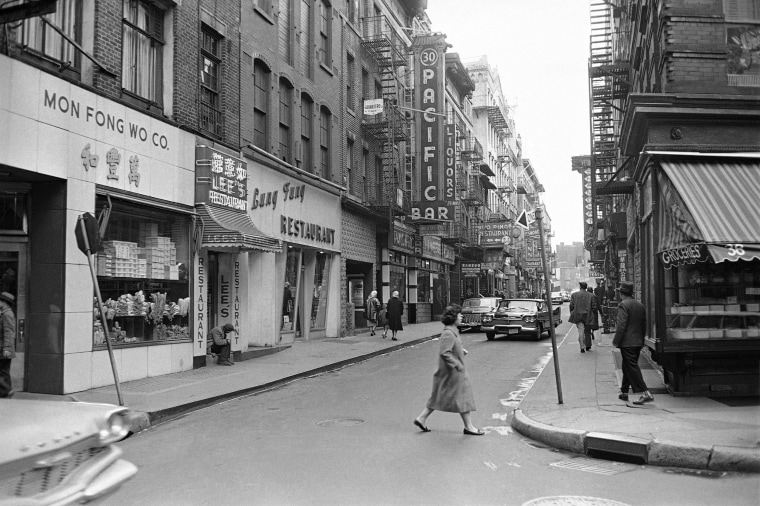

Chin was nine when they arrived in New York's Chinatown in 1963. She struggled to learn English but quickly caught up. By seventh grade, she was learning a third language - Spanish. She applied to, and through a specialized entrance exam and supplementary summer school program, was admitted to the Bronx High School of Science, the only one of three prestigious New York public schools that at the time admitted female applicants based on the results of a test.

Traditionally, many Chinese-American parents enroll their children in prep courses for the specialized high school exam, which today covers eight city schools. In a public school system that graduated 68.4 percent of students in 2014, a passing score is seen as a ticket to a top-flight, free education and is considered the ultimate academic accolade.

So when Mayor Bill de Blasio, whose own son attends Brooklyn Tech - a specialized high school, suggested last August that criteria other than exam scores be used for admission - in an effort to diversify the mostly white and Asian student bodies of some specialized schools - some Chinese-American parents were worried.

“My position was like, look, we need to make sure opportunities are available to everyone,” Chin said, adding that all city public school students should have access to classes to help them prepare for the exam.

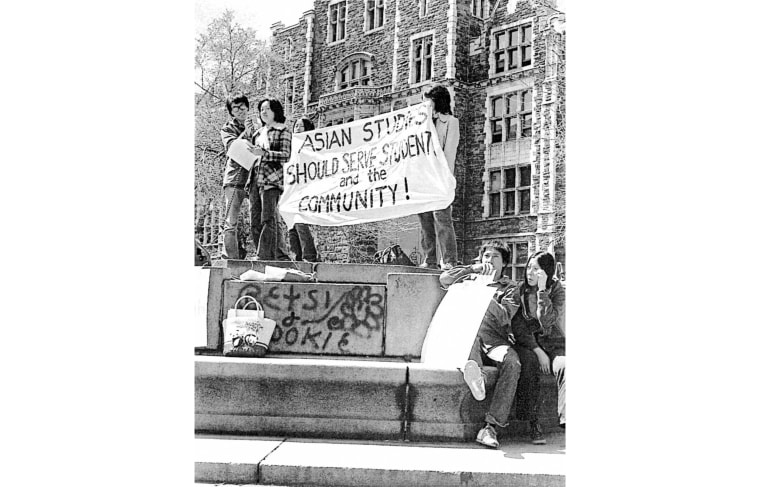

Like her acceptance to Bronx Science, Chin’s ascent to New York’s City Council was similarly marked by failure first, then success. While attending City College in 1974, Chin helped to found Asian Americans for Equality, a non-profit community organization. She had been elected to the Democratic State Committee for two terms. And she had also served on two community boards. Her resume was strong when she first ran for office in 1991.

But voters in Lower Manhattan, she says, were not yet ready for a Chinese-American councilwoman.

“We didn’t have enough of the base,” Chin said.

“It took many years of building from 1991 to 2009.”

So she focused on the next race in 1993, on mobilizing her constituents, and "demystifying" the voting process for immigrants. She filed a lawsuit against the Board of Elections to mandate that ballots and materials be provided in Asian languages whenever voters who read and speak those languages make up five percent of a council district.

“Some people were afraid to use [the voting machines],” Chin said. “So we rented them for people to try them out.”

She lost in 1993. And again in 2001. But in 2009, Chin eked out a primary victory, defeating incumbent Alan Gerson by just 1,021 votes, and won the general election with 86 percent of the vote, becoming the first Asian-American woman elected to the City Council.

“Some people from the other areas were shocked,” she said. “It took many years of building from 1991 to 2009.”

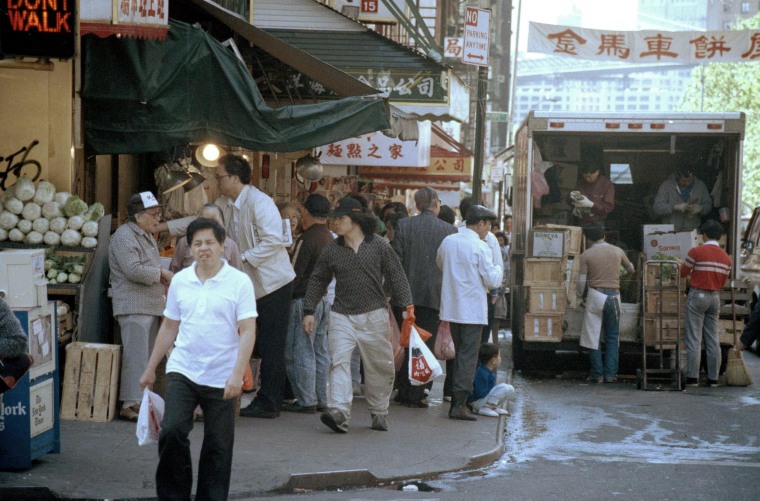

Chin's constituents are not just from Chinatown; her district stretches across all of Lower Manhattan, including high-rent neighborhoods like Soho, Tribeca, and the Financial District. But Chinatown is where Chin grew up, and she naturally worries that some of the main tourist draws have become fake designer bags and watches.

“I don’t want Chinatown to be known as the counterfeit capital,” said Chin.

Police have targeted counterfeit sellers in Chinatown with varying success, prompting Chin to introduce a bill in 2011 to empower law enforcement to fine those making the purchases. “The fact that you have a law letting people know - that would deter a lot more,” she said.

There was a hearing for the bill in 2013, but it was never brought to a vote, said Sam Spokony, Chin’s spokesman. Chin hopes to reintroduce an amended version before the end of the current council term in 2017, he said.

“I’m not afraid to speak out, and not everyone agrees with me in Chinatown.”

But some Chinese-American business owners have expressed fear that such a measure might discourage tourists who buy fake goods from dining in Chinatown, thus hurting the local economy. Chin disagrees. “The sad part is, a lot of people come, buy the stuff, and leave,” she said.

More recently, Chin has made news for her positions on two other controversial issues. Last month, the New York Daily News, a local newspaper, criticized Chin in an editorial for not fully backing a plan to revitalize Lower Manhattan’s iconic South Street Seaport, badly damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Chin, who supports rebuilding the seaport, has expressed concern that part of the $1.5 billion proposal, calling for a 494-foot tower to house a school and apartment units, would alter the character of that area.

Spokony said Chin, who called the editorial a “gross mischaracterization,” was still in talks with the developer, Howard Hughes Corporation, whose project to build a new Pier 17 near the seaport received approval from Chin and the City Council in 2013.

Chin’s praise for a grand jury’s indictment of Peter Liang, the Chinese-American New York police officer accused of fatally shooting Akai Gurley in a Brooklyn housing project last November, also brought her “flak” from some Chinese Americans who criticized her for not supporting one of her own. New York Police Commissioner William Bratton has called the shooting an accident.

“I’m not afraid to speak out,” Chin said, “and not everyone agrees with me in Chinatown.”

Chin added: “I think [Liang] has to go through the judicial process and not make any excuse that it’s an accident.”

Nonetheless, many Chinese Americans still view Chin as a sympathetic face in the community, as someone who can help navigate the bureaucracy of municipal government.

That much was evident one late afternoon in her district office on Park Row, just steps away from police headquarters. While the commuter van drivers and operators were sorting out their summonses, a Chinatown resident came in from the cold and signed a log to meet with staff. He had the hiccups, and the older woman working the front desk offered him some tea she had just brewed. The man accepted, and the two chatted in Cantonese while he waited.

“People are more comfortable when you speak their own dialect,” said Chin, who speaks Cantonese, Taishanese and Mandarin. “It helps a lot.”

Chin said she plans to run again in 2017, but chuckled when asked if she would seek higher office after that.

“I think I’ll be happy to complete my term in the City Council, and then I can spend time to do things I never had the opportunity to do,” said Chin, whose husband is a public school teacher and whose 33-year-old son, a photographer, is taking classes to become certified to teach high school.

When pressed to name one thing she would do, Chin let out a long laugh as she thought of an answer.

“There are so many things,” she finally said, “but probably learn how to play the piano.”

Follow @NBCAsianAmerica on Twitter and like NBC Asian America on Facebook.