Every summer, Nikiko Masumoto anxiously handpicks the first organic peach of the season on her family’s farm, hoping the care and love the Masumotos have put into the fruit's cultivation will bring a smile to whoever eats it.

"Picking the first peach of the summer feels like coming home," Masumoto, an organic farmer at Masumoto Family Farm and performance artist, told NBC News. "That's the beautiful feeling I hope people sense when they bite into one of our peaches or nectarines."

Today, the 80-acre nectarine, grape, and peach farm in California’s Central Valley is a symbol of hope and resilience and a tribute to Masumoto’s grandparents, great-grandparents, and the approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans who were forced into incarceration camps following the signing of Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942.

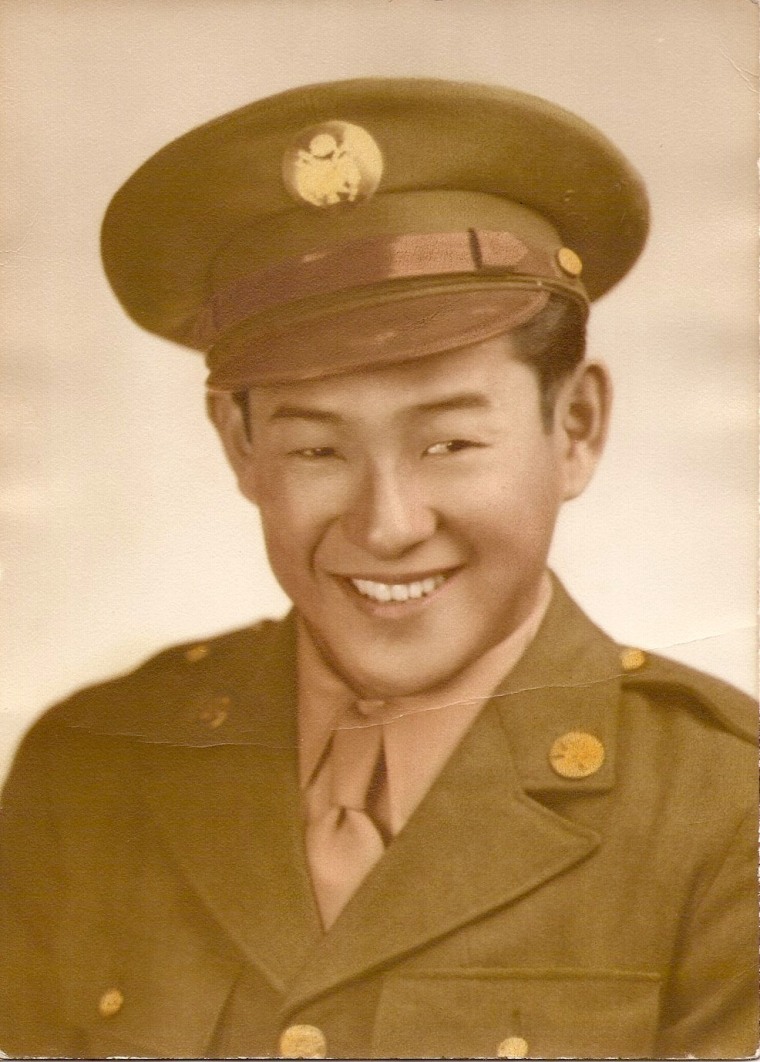

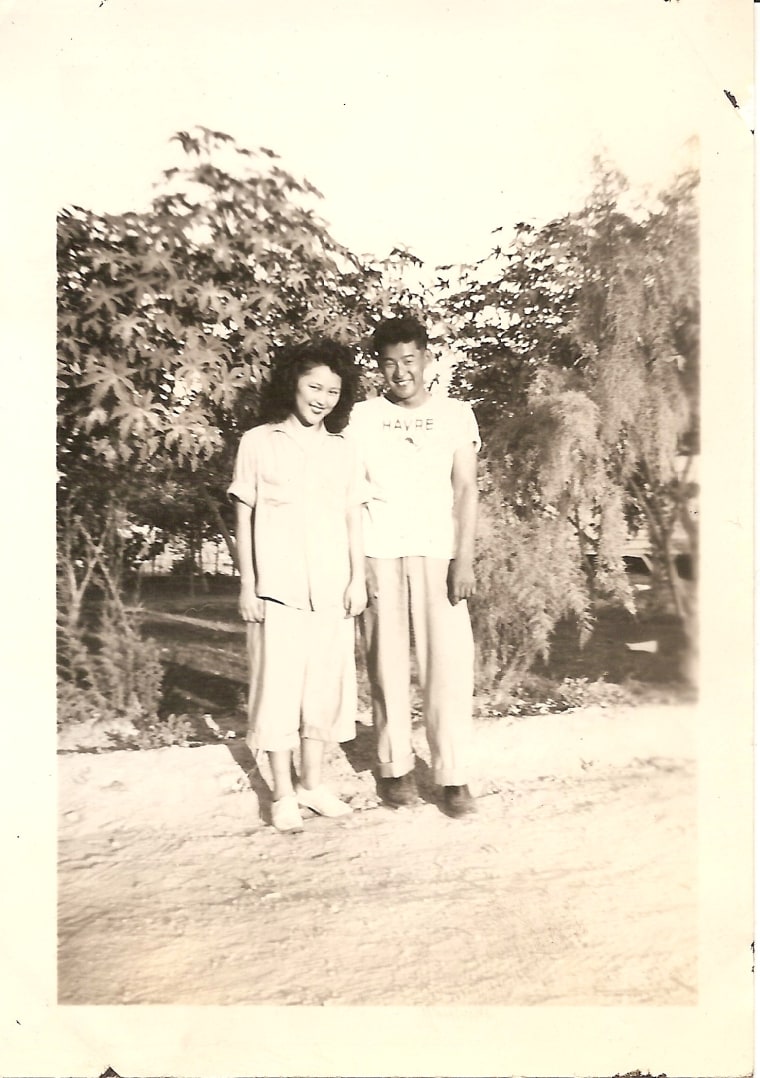

The first 40-acres of the farm were purchased by Masumoto's grandfather, Joe Takashi Masumoto, in 1948, a few years after the Masumoto and Sugimoto families were forced into the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona.

RELATED: 75 Years After Executive Order 9066

Following World War II, Joe Masumoto came back to California and saved enough money to buy land and create a home for the next generation of Japanese-American farmers, Nikiko Masumoto explained.

“After decades of working the soil, he brought it back to life and it’s now this thriving organic farm that I am blessed and so honored to be able to work today,” she said.

Before the war, Masumoto’s family were farm workers, but anti-Asian immigration laws like the California Alien Land Law of 1913 made it difficult for Asian immigrants to own land in the state, Masumoto noted, comparing past restrictions to the recent executive order on immigration, which limited entry into the U.S. from seven Muslim-majority countries.

“The reality is that we have not learned anything from our history of exclusion…of letting fear misguide us,” said Masumoto. “The language and the framing of these new executive orders are just a repeat of the same type of racist hysteria that drove Executive Order 9066.”

Seventy-five years after the signing of Executive Order 9066, Masumoto continues to reflect on the strength and resilience of her jii-chan and baa-chan (grandfather and grandmother) and the many sacrifices her ancestors have made to preserve the legacy of the family farm.

“I get to literally live with those roots, the vines [my grandfather] planted are still thriving and growing and producing food on our farm and the power of that act is never lost on me — his resilience to really claim a place of belonging against all odds,” she said.

Masumoto hopes to continue to share her grandparents’ stories — and the stories of the incarcerated Japanese Americans — through her performance art and ongoing research focused on preserving Japanese-American memory.

“I can nourish [my grandfather’s] stories through my life performance and that same mentality is exactly what motivates me to farm,” Masumoto said. “There is a priceless richness hidden in the roots. If only we can be awake enough to make sure we nourish them to feed our future generations, that to me is the power of connecting the arts and farming.”

Growing up, her grandmother didn’t openly speak about her incarceration experience or the loss of her father — Masumoto’s great-grandfather — Masumoto said.

“As I understand it, her survival mechanism to get through camp was to bottle her emotions and growing up, we didn’t talk a lot about camp openly,” she said.

RELATED: A Lookback at the Decades-Long Embargoed Incarceration Camp Photos

After an overwhelming visit to the site of her grandmother’s incarceration camp and seeing her grandmother participate in a second high school graduation ceremony in 2006, Masumoto created a visual storytelling piece, “Rites of Passage,” in which she compared her educational experiences with those of her grandmother, who finished her high school education at the camp.

“It wasn’t until I visited the internment site that I had ever placed my baa-chan’s youth and life in a context similar to mine,” Masumoto said. “I couldn’t imagine being forced to be in a school that…is in a place that represents the antithesis of possibilities.”

Finding Her Calling

Growing up as the eldest child of mixed German-Japanese descent, Masumoto often contemplated the idea of success and what she wanted to ultimately pursue.

“Looking back, I think that I experienced what a lot of rural kids experience which is … there’s definitely success and job opportunities are almost always defined as somewhere else. Like success doesn’t live in rural America, success lives in metropolitan, urban America,” she said.

“I get to literally live with those roots, the vines [my grandfather] planted are still thriving and growing and producing food on our farm and the power of that act is never lost on me.”

When Masumoto was in college, she had no intention of moving back home to help with the family farm.

“Like a lot of farm kids and rural kids growing up in the Central Valley, I completely was oblivious to the magic that was happening around me, especially on our organic farm,” Masumoto, who has now been working as a farmer for six years, said.

But after taking an environmental studies class at the University of California, Berkeley and delving more into her research on Japanese-American history in graduate school, she developed an understanding of the importance of farming and how she could combine it with her interest in performance art and Japanese-American memory.

“I came to realize one of the boldest, perhaps courageous things I could do with my life would be to come home and become the next generation to work the same farm,” she said.

RELATED: Digital Project Aims to Preserve Stories of Incarcerated Japanese Americans

To further her passion for performance art and farming, in 2012, Masumoto started a community storytelling project called the Valley Storytellers Project where community members were invited to share stories about hunger in the Central Valley. Local writers then transformed the stories into original plays. She also helped curate and collaborated on an “art-guided bus tour” along Highway 99, which runs through Central California.

“When I’m approaching my performance work, I always pause and think about my grandparents because they not only help me feel a little less nervous, but they also help me get back to my roots, to the unseen powered strength that I feel like I’ve inherited,” she said. “I think about the performance as my practice of nourishing these roots.”

RELATED: ‘Only the Oaks Remain’: One Woman’s Fight to Preserve Her Heritage

Connecting Art to Farming

Farming together with her family has been a life-changing experience for Masumoto. In 2013, Masumoto, her father, Mas, and mother Marcy authored a cookbook featuring recipes and stories from the farm in “The Perfect Peach.”

In December 2016, Masumoto was invited to perform her one-woman show, “What We Could Carry,” at the White House. Her performance was based on the testimony given at the 1981 and 1980 Hearings of the Congressional Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in Los Angeles. It was also the culmination of her master’s thesis degree at the University of Texas at Austin, where she focused her research on Japanese-American history.

“On the one hand I was completely honored and I felt this flowing of emotion because it’s pretty remarkable that a fourth-generation Japanese American could travel to the White House — one of the iconic representations of our government — and be able to tell the stories of my grandparents and my community.”

During her performance, Masumoto couldn’t stop thinking about her grandparents and her continued promise to never stop telling their stories.

“It was with a very complex emotional experience that I took in that event both as a call to renew my promise to my grandparents to never stop telling their story,” she said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.