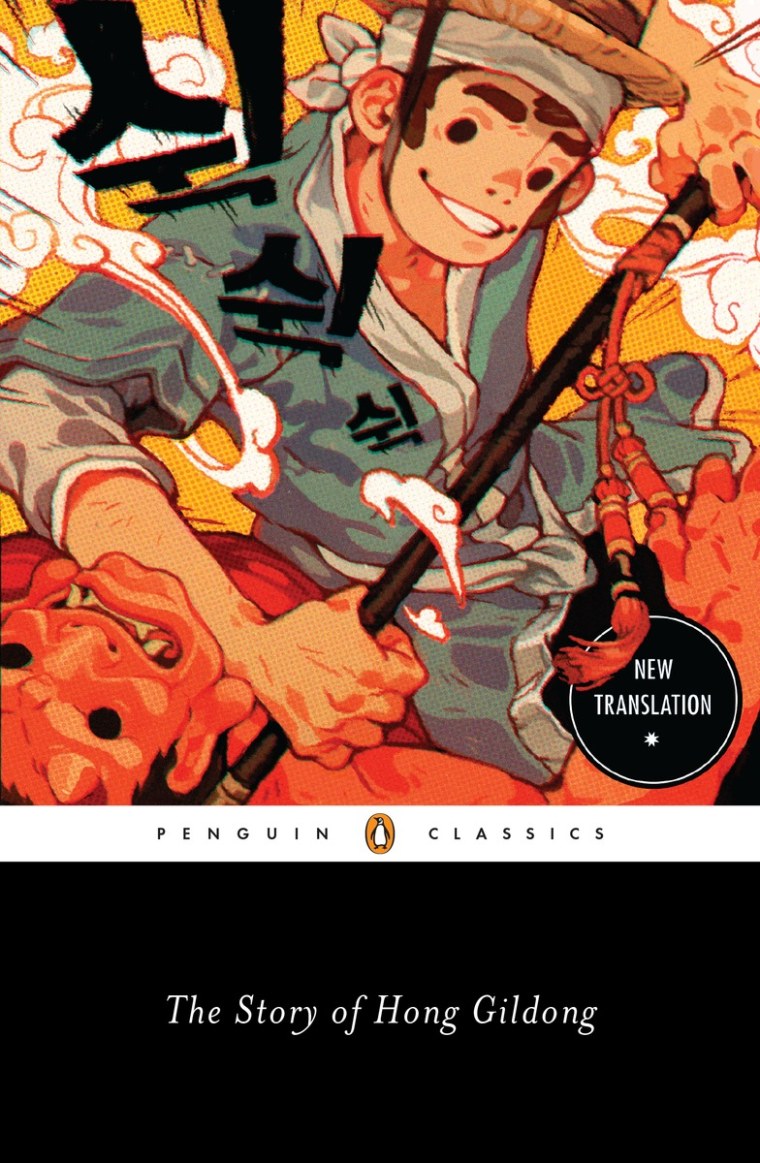

“The Story of Hong Gildong,” a Korean folktale that has been compared to Robin Hood for the parallels between the main characters, is one of the most prominent works of Korean literature. The latest translation of the story — by Minsoo Kang, a professor of European history at the University of Missouri-St. Louis — was published in March as a Penguin Classic, the first work translated from Korean to receive that distinction.

While Kang initially thought the task of translating the story would be a fairly easy one, he told NBC News that his research led him to revelations that fundamentally change the context and history of the story. We spoke to Professor Kang over the phone about these discoveries, the importance of “Hong Gildong,” and his next projects.

What made you decide to translate “The Story of Hong Gildong”?

When I was an undergrad, I took this class on the introduction to cultural history, and one of the books we read was a book by the great historian Eric Hobsbawm called “Bandits.” It’s a book about why we sometimes make heroes out of outlaws. In the chapter on “noble robbers,” he started describing this character who’s an outlaw but actually fights for the people and as a result is a hero. Obviously for Americans the person they think of immediately is Robin Hood but what Hobsbawm did was show that that same archetypal figure you can find anywhere in the world. You can find it in Sub-Saharan and Northern Africa, the Middle East. There are Japanese, Chinese, a bunch of Eastern European versions. [Hobsbawm] shows that rather than Robin Hood being the standard figure, he’s the English version of a very universal figure.

Having grown up in Korea, my mind went immediately to Hong Gildong. Like most Koreans though I had never actually read the classic text that’s called “The Story of Hong Gildong” because Koreans feel like we are all too familiar with it. That story has been told so many times in drama, in film, in modern novels, for children in comic books and animated movies and so on. Most Koreans think they know the story so they don’t bother to actually read the book.

At the time I decided to write my class paper on Hong Gildong, where I applied Eric Hobsbawm’s ideas to analyze it. There was a translation available then, made in the 1960s by Marshal Pihl, and it as a good translation, but I felt there was something missing from it. It felt kind of short, as though it were the abbreviation of a longer story. There were story threads that were mentioned and just forgotten. I decided I would look into it later and see if it was the right translation. Later on I found on that the text it was translated from was an abbreviated version, and that there are 34 different manuscripts of “Hong Gildong” in fact.

What was the most difficult part about translating this work?

When I first started working on [the translation], I thought it would be an easy task. That I’d write an introduction on why the story is so important, and tell why it’s so important. I soon realized it would be a really complicated task. There were so many manuscripts, but I figured the longest one is probably the most important one. It’s the oldest, so either the original or the closest to the original work. I also realized the scholarship behind the existence of the novel was incredibly complicated. What most Koreans thought about the work is actually wrong. Most Koreans think it was written in the early 17th century by Heo Gyun.

I think one of the reasons why a lot of Koreans would still really like to believe that it was Heo Gyun who wrote this story, is that you have this beloved work of classic Korean literature, and I think a lot of Koreans would like to believe that one of the most illustrious and powerful families of the Choseon dynasty, also a renowned poet, was behind it. But if you look at the evidence, it points to the fact that he probably didn’t write it, that it was the work of some anonymous commoner who wrote it, mainly for profit. At the time there was a market for popular literature that was marketed to commoners. Evidence points to the fact that “Hong Gildong” was a product of this system. One of the reasons Koreans want to believe in Heo Gyun is intellectual elitism. I think the idea that at his beloved work was written by someone of no importance for profit is somehow denigrating to its quality to some, but the greatest works of literature came out of the hands of commoners for the purpose of profit. Charles Dickens, for example. Shakespeare.

Are there any other revelations you came across when researching for the translation?

There’s also this common refrain that the work is important because it’s the first original work of fiction done in the Korean language, Hangul, and not Chinese. It’s seen as this subversive work that’s anti-feudalistic, and if you read it carefully, although it is subversive in ways, there are also a lot of conservative elements. It’s hard to argue that it’s anti-feudalistic.

A competent scholar would be able to tell you “this is a 19th century work” or “This is from the middle ages.” If you read “The Story of Hong Gildong,” it’s so quintessentially 19th century. It boggles the mind that anyone could have thought it came from an earlier period, because the style of literature changed century to century. And if you compare “The Story of Hong Gildong” with other works like that, with popular adventure stories that came out of the 19th century, it fits right in with them. Whereas if you go back to the 17th century, which is when Heo Gyun supposedly wrote it, there is no example of a work like this being produced.

If you look at what the Choseon Dynasty was like in the 19th century, this kind of popularity makes perfect sense. The old dynasty had lasted for over 500 years, one of the longest-running dynasties in the history of the world, and the whole thing was shattering into pieces. The country was in turmoil. All the kings of the 19th century proved to be completely inept. All these foreign powers, not the traditional ones of China and Japan, but new ones like England, the United States, and France, were coming in and the country was in no position to handle any of that. The attempt to modernize Korea internally, like Japan in the Meiji period, failed, and as a result led to the country being colonized by the Japanese. It must have been a confusing and chaotic and unsettling period, but exciting at the same time. Things were getting modernized very quickly and there were a lot more opportunities for commoners to do things in society.

How did “The Story of Hong Gildong” become a Penguin Classic novel?

There’s a wonderful journal called “Azalea,” that comes out of Harvard publishing, and it published my first verison of “Hong Gildong.” My editor at Penguin, Sam Raim, picked up a copy of it, and he was actually actively looking for Asian translations at the time.

As a Korean, I’m not only really gratified that it made it into Penguin Classics, the first translated work from Korean, but I really get a kick out of the idea that a beloved hero from my childhood is going to become well-known in the West.

After my talk at the Asian Americans’ Writers Workshop, this really nice man came up to me and he told me that he was adopted by Americans when he was a kid- he’s originally from Korea. And he said it was so wonderful reading [The Story of Hong Gildong], and he felt like he was getting in touch with his ancestors.

Why do you think the book has been so well-received? What would be appealing to readers who aren’t familiar with the story, and don’t have the nostalgic ties to it like you or I might?

I think its success is due to the fact that for the typical American reader, there are things about this work that are fascinating because it’s familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. it’s unfamiliar because of course it’s about the Choseon dynasty and there are things about it, like the law limiting the rights of illegitimate children, and even the kind of magic is different. It’s Taoist magic. For people who don’t know anything about Korea, I think a lot of readers find a lot of it completely familiar. It shares the story of the noble robber with Robin Hood, so I see in a lot of reviews people calling him the Korean Robin Hood. The emotional aspects of the story of the underdog who is underrated. It’s action-packed: there are monsters and assassins and all of that. I think that works really well, and I think readers are learning about culture and history of this country they might not be familiar with, but a story not so different that they would be lost. There are markers that are universal in nature.

Are you working on any other translations? What’s next for you?

I got funding from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea to do another classic novel, and it’s called “The Story of Queen In-Hyun.” I’m very excited about this too, because it will deal directly with gender. The way women have been portrayed and the way women have been thought about in the Choseon Dynasty, in both negative and positive ways. It’s a story that pits two women against each other-two actual historical figures. One is portrayed as the ideal Korean woman—that’s the queen—and the other is kind of a nightmare: the concubine, Jang Huibin.

It reveals a lot about what they thought of women. From a modern perspective it’s very problematic because in that patriarchal society the good woman is supposed to be quiet and suffering and patient and unambitious, and the concubine is condemned and portrayed as evil or being ambitious, proud, active.

This story is as famous as “The Story of Hong Gildong.” Every Korean knows the story of the evil concubine and the good queen. One one hand I think this story and mentality has done a lot of damage to Korean culture. It has inhibited women’s rights. But on the other hand there are countless modern versions of this story. Jang Huibin, the evil concubine, is a way more interesting figure because frankly, the good virtuous queen is boring. I’ve been noticing that in the last 15, 20 years, they have been making the supposedly-evil concubine more sympathetic, more in tune with modernity.

I think in the story of what the story has come to mean, you see the ways the story got transformed in the course of Korean history, and in many ways I’m proud of Korea’s achievements in terms of economy and all that. And in terms of women’s rights we still have a long, long way to go. The fact that South Korea is dead-last in terms of the pay discrepancy between men and women among industrialized countries is a shame. I think this comes about from this mentality that a good woman is supposed to be quiet, obedient, but I also think all of that is changing. Too slowly for my liking, but it’s changing. I think the way the novel is portrayed is an interesting metric of that.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.