Growing up in Long Beach, California, Phatana Ith often felt detached from her identity as a Cambodian-American woman until she began to have conversations with elder women in the community about their experiences during the Cambodian genocide.

As Ith continued to have these dialogues, she felt more connected to her bicultural identity. That feeling pushed her to gather the untold stories of elder women survivors of the Cambodian genocide, which killed 1.7 million people between 1975 and 1979 when the Southeast Asian country was under the rule of the Khmer Rouge, according to Yale University.

The stories have now been formally compiled as an ongoing oral history project called “Out of the Shadows” at California State University, Long Beach.

“I want the female survivors to know that their knowledge is valuable and what they are leaving behind when they are gone ... are stories of resilience, of survival, of love, and of forgiveness."

“I found that I felt connected to my identity through these experiences with the elders and at the same time, the elders felt connected to me and hopeful that their culture and values and stories would live on so long as there was someone on the other end to listen to them,” Ith, who lectures at the university, told NBC News.

Ith’s project focuses specifically on untold narratives of female survivors, many of whom have remained mostly silent since coming to the United States four decades ago, according to Ith.

“I wanted to invite elders, female survivors from the Cambodian community to engage with me with this project and share their narratives on their own terms,” Ith said.

“This was quite an organic process to see this project and vision come to life,” she added, noting that survivors of the genocide can be private about discussing what they experienced.

Ith spoke with female survivors specifically because she realized that Khmer women didn’t necessarily have opportunities to share their narratives “because males are often seen as the authorities of knowledge, and this is true for many societies, not just Khmer society,” she said.

Though Ith didn’t live through the genocide, she has many family members who have survived it, further prompting her to learn more about her culture, her roots, and her history.

She immersed herself in cultural events, attending ceremonies at Buddhist temples and doing everything she could to learn the Khmer language and reconnect with her family story.

“I struggled with identity and these struggles came from a deeper place and that was not really knowing where I came from and because I didn’t know who I was or who I could be,” she said. “I tried everything I could to find my identity."

Ith also said that, when she realized the wealth of information the community elders had, she felt she needed to preserve it for future generations.

In collecting stories from survivors of trauma, Ith said there is a need to approach research with sensitivity, cultural sensitivity, and trauma-informed care.

Experts need to be prepared to treat trauma as receivers of information and stories, she added.

“We have no intention to go in and get these stories and leave these individuals worse than they were by retriggering these traumatic experiences,“ Ith said. “Not at all. We want to go in and we want to be invited in, and we want to be clear that what we intend to do is make this community or be a part of this community healing.”

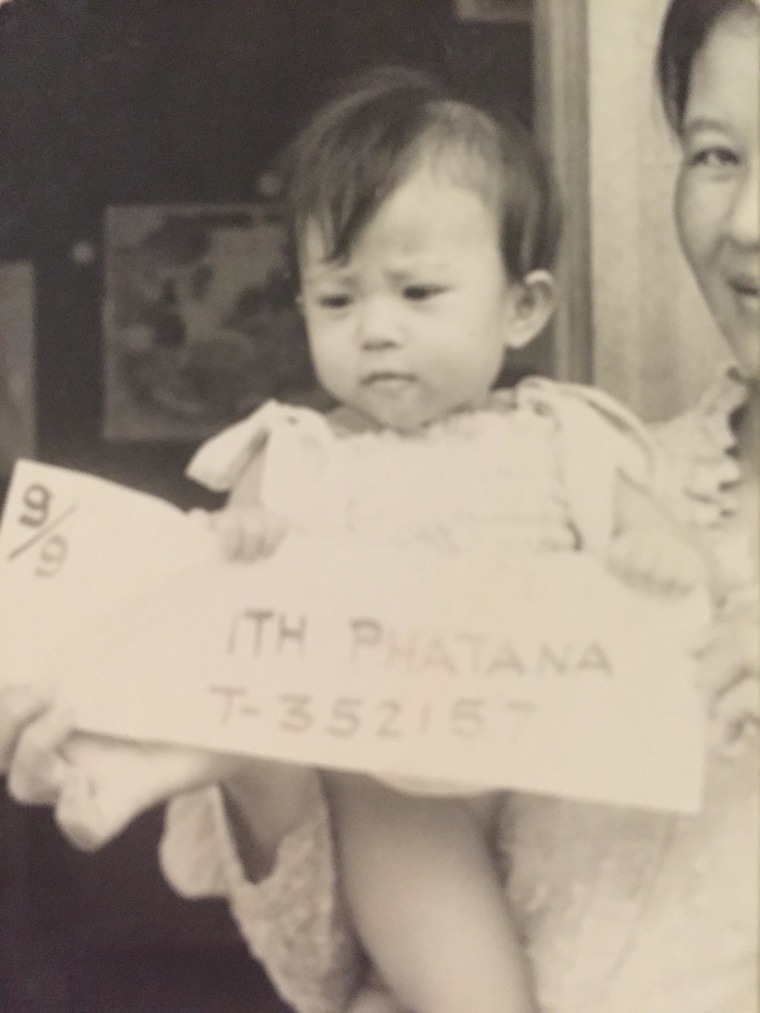

Ith said her hometown of Long Beach contains one of the largest Khmer populations outside of Cambodia. Her family left the country shortly after she was born and arrived in the U.S. when she was 7 months old. They landed in Ohio in 1982 and moved to Long Beach in 1984.

“I remember it was a dangerous time to be in Long Beach in the ‘80s,” she said. “During that era, there were a lot of gang wars, and there were fights for territory and Cambodians were the new kids on the block.”

Many of Ith’s family members — including her mother — survived the genocide, but the trauma lived with them for generations, according to Ith.

“It was in 1975 when the Khmer Rouge came and took over [my mom’s] city and she lost her husband...my mother’s husband was executed, so she was widowed at the onset of the genocide,” Ith said, adding that her mother had eight children who were relocated to a labor concentration camp and saw her brother executed in front of her own eyes.

“The things that they saw were atrocious, watching executions of their own family members,” Ith said.

From conversations she had with her mother, Ith said her mom would gather her children and tell them that if anything were to happen to her, she had hidden family jewels in thehome. “She hoarded certain jewels when they were evacuated from the city and kept them in secret compartments,” Ith said.

According to Ith, survivors of the genocide believed that “if you were deemed not fit to work, you were going to be killed.”

Ith’s mother told her a story about trucks that were loaded with people during the night. The trucks would leave in the middle of the night, and, in the morning, they were empty. “You never heard of these people again, and it was assumed they were mass executed,” Ith said.

The oral history project comes during the remembrance of the 42nd anniversary of the Cambodian genocide. Several cities across the nation, including Long Beach, organized candlelight vigils on Monday, April 17, to honor the lives lost. These memorials play a vital role in healing and continuing to share stories, according to community members and organizers.

“The imprints of genocide are very evident in Cambodian refugee homes but the relationship of younger generation Cambodians to this genocidal history is mediated by language loss, temporal and cultural disconnect, and lack of information,” Khatharya Um, an associate professor of Asian-American and Asian diaspora studies at the University of California, Berkeley, told NBC News. “Many younger generation Cambodians, thus, feel the weight of this historical tragedy but are often without the tools to make sense of it.”

“Even though this story is emotional, it really is helping me heal, and I think more people need to learn more about the effects of genocide,” Savong Lam, a Washington state-based genocide survivor and one of the organizers of the National Day of Remembrance Candlelight Vigil in Tacoma, Washington, told NBC News.

Earlier this month, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors approved a motion declaring April 17, 2017, “Cambodian Genocide Remembrance Day.”

“Having this recognition from the county is a big statement for us and I think that it speaks to something that we’ve wanted all along, which was to belong to this community and to belong to this nation,” Ith said.

And to honor and remember the lives lost in Cambodia, California state Sen. Ricardo Lara introduced a resolution recognizing Cambodian Genocide Memorial Week from April 17 to 23.

"Long Beach is home to the nation's largest Cambodian population. It's important to me that the Cambodian Genocide is recognized each year to honor the lives lost,” Lara told NBC News by email. “The resilience of survivors and their families is a true testament to the human spirit.”

Last May, the Long Beach City Council approved a proposal for the development of the Cambodian Genocide Memorial Park (also known as Killing Fields Memorial Garden) in the city’s Cambodia Town.

Paline Soth, one of the organizers of the 42nd Anniversary Killing Fields Memorial Commemoration, told NBC News that the garden memorial is scheduled to be completed within the next 18 months, thanks to a $150,000 grant from the city.

“Our purpose is simple: memorial, respect, remembrance. We do not forget. We will not forget our people who suffered tremendously and the genocide,” Soth said. “This is killings of the people by their own people and so this is something that is very significant to the people of Long Beach.”

"We want to go in and we want to be invited in, and we want to be clear that what we intend to do is make this community or be a part of this community healing.”

Ith hopes her oral archive project will provide a space for healing and an opportunity for future generations to reflect on stories from elder women and survivors.

“I want the female survivors to know that their knowledge is valuable and what they are leaving behind when they are gone — because they are aging out of our population — what they leave behind are stories of resilience, of survival, of love, and of forgiveness,” she said.

She also hopes that her oral archive project can be something that other communities use as a format for approaching sensitive stories about war and genocide.

“Genocide is going on as we speak, and so how do we provide resources that show care, compassion, and sensitivity for those people who come out of these horrible situations?” Ith said. “I think this project and research can contribute to that in some way.”

Follow NBC Asian America from Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.