During a hot summer day in the Valley, volunteers at Dr. Sanbo Sakaguchi Hall serve fresh sashimi to seniors at the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center in Pacoima, California.

Since 1959, the Center has worked to preserve the dreams of Japanese Americans who returned to the San Fernando Valley after World War II. Many had hoped for a community center that would save their stories for generations to come.

“They had a dream of coming to this country and raising their families, and then they were disrupted by the war where they struggled through that and survived. This center represents their spirit,” Nancy Oda, former president of the Center, told NBC News.

The Center was built with the help of $150,000 raised by Japanese American farmers and the North Hollywood Farmer’s Association entire treasury. For nearly 10 years before the construction of the Center, many Japanese Americans lived in trailer camps in Sun Valley in the San Fernando Valley.

“Older people lived in trailer camps after the war, and because of social conditions in the camp, the elders were concerned about juvenile delinquency,” said Oda.

At a time when mistrust ran high, the Center offered a safe place where Japanese Americans could work towards rebuilding their lives through education and community programs.

“They had a hard time breaking into jobs," said Oda. "But education was more important than material things."

"I believe that my work now is to preserve what the elders have done."

56 years later, despite a few financial setbacks, the Center is as busy as it's ever been. Senior hot meals are served twice a week by long-time members of the Center, along with a range of activities like ballroom dancing, Mahjong games, Japanese calligraphy, and judo. Many of the regulars spend time in the gymnasium where they embrace the sounds of the taiko drum and the ukulele. Over the past few decades, the Center established two senior citizen facilities – one of which was sold in 2012.

“All these elderly people at the center, they feel safe. They don’t have the guard towers. They don’t have the searchlights. They play Mahjong, ukulele, and you can see lots of energy. They can live a full life,” said Oda.

Her family - along with other families that settled in the San Fernando Valley - have had a long history and connection to the Center’s roots. Her parents and older sisters were interned at Tule Lake Segregation Camp in 1943. Her children grew up at the Center and were heavily involved in judo, basketball, and various other activities. They later passed the tradition onto Oda’s grandchildren.

“This community center is very important to me and I believe that my work now is to preserve what the elders have done. In camp, they learned about sticking together,” said Oda.

The Oda Family Story

Oda’s family were survivors of the internment that interrupted the lives of 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast, forcing them to leave behind homes, businesses, and lives they'd built over years for incarceration behind fences and armed guards. After Executive Order 9066 was signed, hundreds of thousands of people of Japanese ancestry --two-thirds of whom were American citizens -- were placed in relocation centers.

Oda, now 70, was born in the internment camp in Tule Lake, one of 10 largest camps on the West Coast known for its high security guard towers, and 12-foot barbed wires used to detain “enemy aliens.” The Tule Lake Segregation Center interned approximately 18,000 men, women, and children.

Within 48 hours of being notified, the Oda family was forced to close down the Hilltop Market, their grocery store business in East Los Angeles. They sold new equipment they had purchased for their store for little money in exchange. Oda’s father also left behind a house he had purchased in 1930 and transferred it to the custody of trusted customers from his grocery store.

Before leaving, Oda’s father locked many philosophical books that provided him comfort and strength in the basement of his home. “He put a lot of his precious things in the basement," Oda recalled, "whereas a lot of people burned their Japanese memorabilia.”

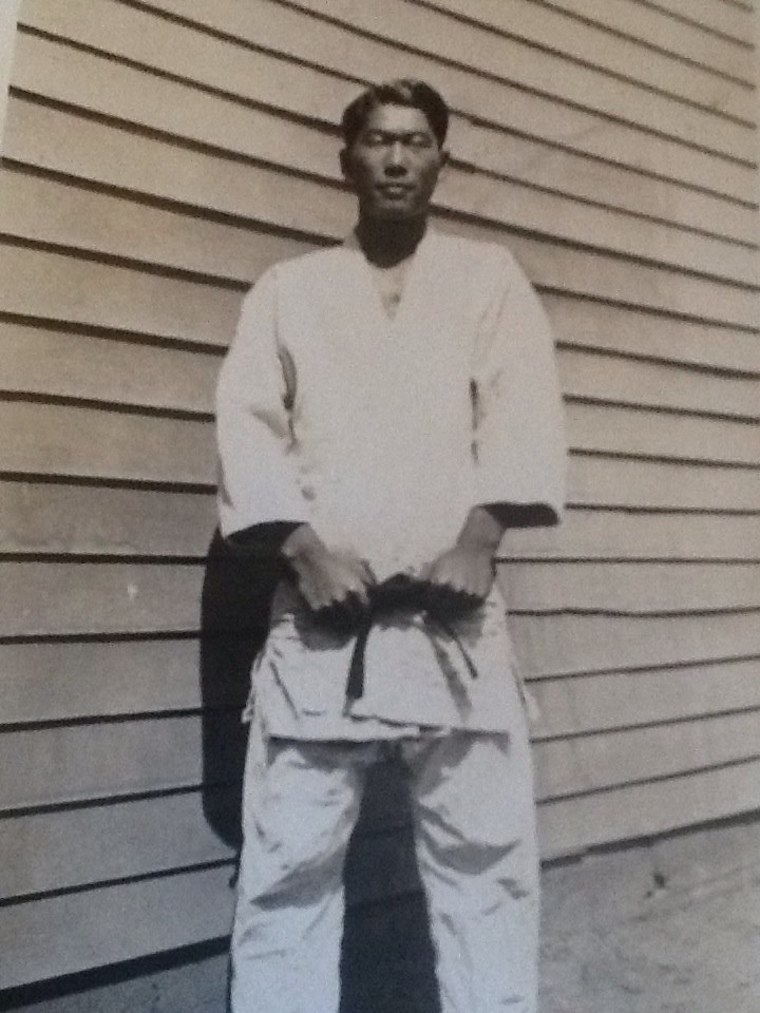

Oda’s father rounded up the family, went to Lancaster to gather the rest of the family, and reported back at a relocation camp in Poston, Arizona, where he was a judo instructor.

He felt that writing - the pen - was his only way of contributing to society. By making a record of the events was his contribution.

Sports and judo were always a big part of the Oda family’s life. Inside the camp, judo provided Oda’s father with a sense of solace and leadership while helping others stay active while confined.

“My father has been a judo man all his life. He established a judo dojo there and eventually the U.S. published a survey to draft more soldiers because they needed more personnel,” said Oda.

Oda’s father – Tatsuo Ryusei Inouye - was born in the U.S., and raised in Japan. He was considered a “no-no” boy after answering “no” to questions 27 and 28 in the infamous loyalty questionnaire.

“He had a very big decision to make because the question asked, ‘would he be loyal to the U.S. and serve in the Army?’ He said no,” said Oda. Her father, she says, felt compelled to answer "no," because his brothers were still living in Japan. Answering "yes" would put him at war with his own family.

The family was later transferred from Poston, Arizona to Tule Lake in 1942, where Oda’s father was imprisoned in a double fence compound or a “prison within a prison” at the camp, under tight watch and security as one of the highest ranking judo officers.

Every morning at Tule Lake, a camp officer would require detainees to line up in groups and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Oda says her mother struggled to participate, spending each day feeling like a prisoner in her own country.

“My mother would cry when they would do the Pledge of Allegiance with soldiers with armed guards. It was very hard for her to even tell us it was that hard,” she said.

From the stories her mother and two older sisters told her, many Japanese Americans interned at Tule Lake would use their time to reflect, meditate, create, and write, in an effort to maintain what was left of their dignity and faith at a time when the U.S. government and the public viewed them as suspicious and disloyal.

“Japanese people are very philosophical. They would perceive a searchlight as the moon beam under which they could meditate. They would get a carrot and carve a little Buddha for Buddha’s birthday,” said Oda.

One of the artifacts Oda’s father brought back from the camp was a Shinto shrine that has been in the Oda family for decades.

"When they came back home with me, I was just a baby. We really treasured it as a family because it’s a sign of faith and hope,” said Oda.

"I’ve loved teaching because that’s kind of the kernel of my being – to teach, especially our culture."

The family eased back into life outside the camp. By day, Oda’s father was a gardener in Monterey Park, California and by night, he would teach judo in East Los Angeles.

But lingering prejudice against Japanese Americans was pervasive, and rebuilding their lives wasn’t easy. “People had more prejudice after the war than before the war,” said Oda.

Though her father didn’t openly discuss his internment experiences, he kept a diary in camp that revealed his anger and frustration. The diary is currently being translated by a Fulbright scholar from Japan.

“He felt that writing - the pen - was his only way of contributing to society. By making a record of the events was his contribution,” said Oda.

Unlike Oda’s older sisters who had been very traumatized by the experience in camp, Oda had a childhood that was very different – one that consisted of birthday parties, piano lessons, and a full education.

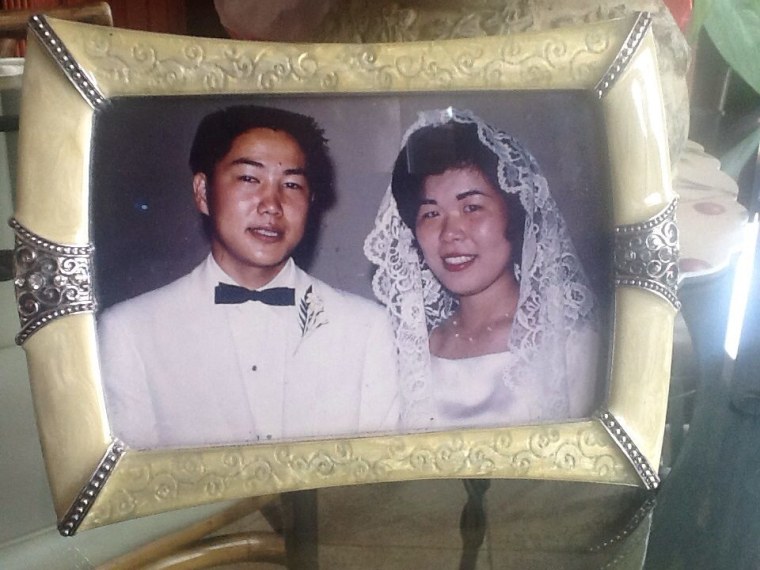

Growing up, Oda was raised in East L.A., attended a private school for Japanese-American children, and eventually went on to attend Garfield High School where she met her husband Kay -- a star basketball player. He attended UC Riverside on a scholarship and later went on to coach basketball at the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center for the next 40 years.

Oda went on to receive her undergraduate degree from UCLA where she studied East Asian studies and became an educator for the next 35 years. Along the way, she also picked up her master’s degree at Cal State L.A. and taught students in Title I schools in Sylmar, where she found herself to be one of the few Asian-American administrators.

“I’ve loved teaching because that’s kind of the kernel of my being – to teach, especially our culture.”

"Only the Oaks Remain"

These days, Oda has been busy finalizing plans for a travel exhibit memorializing Tuna Canyon Detention Station in Tujunga, through her leadership with the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition. The exhibit will move forward with a $102,190 grant from the National Parks Service Japanese American Confinement Sites that was announced June 18.

The former detention station – which is currently the site of a golf course - is located 10 miles from the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center. The former detention station originally served as a Civilian Conservation Corps camp site that was later transformed into a detention center for Japanese Americans investigated by the U.S. Department of Justice.

But over the years, the site's history has been erased from the public’s memory. Oda wants to change that.

The grant, sponsored by the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center, will help bring the stories from the Tuna Canyon Detention Station to the forefront through a traveling exhibit titled, “Only the Oaks Remain.” The exhibit will feature more than 50 photographs that were taken by Tuna Canyon officer Merrill Scott, in addition to newspapers, and other archival documents.

“These photos will show what Tuna Canyon looked like and reveal what life was like inside the camp,” according to a statement from the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center.

On June 25, 2013, the city of Los Angeles officially recognized Tuna Canyon Detention Center as a historic cultural monument. After World War II, the site went through various transformations. It became an L.A. County probation school for boys and is now a golf course.

Oda’s goal is to grow the traveling exhibit and make sure the history of the sites along the West Coast are not forgotten. The main monument will be located under a grove of oak and sycamore trees.

For now, Oda hopes the travel exhibit will initially be booked at the Japanese American National Museum in Downtown L.A., and is on the lookout for other venues. She is also confident that the Tuna Canyon Detention Station will be recognized as a national historic site in the near future.

But time, she says, is of the essence. “We’re losing momentum so to speak, because they [elders] are dying off. So to collect these stories, we’re running out of time," said Oda. "By the time this is built up, I’ll be 80 years old. So I have to think I am training the next generation. I’m going to set the stage."