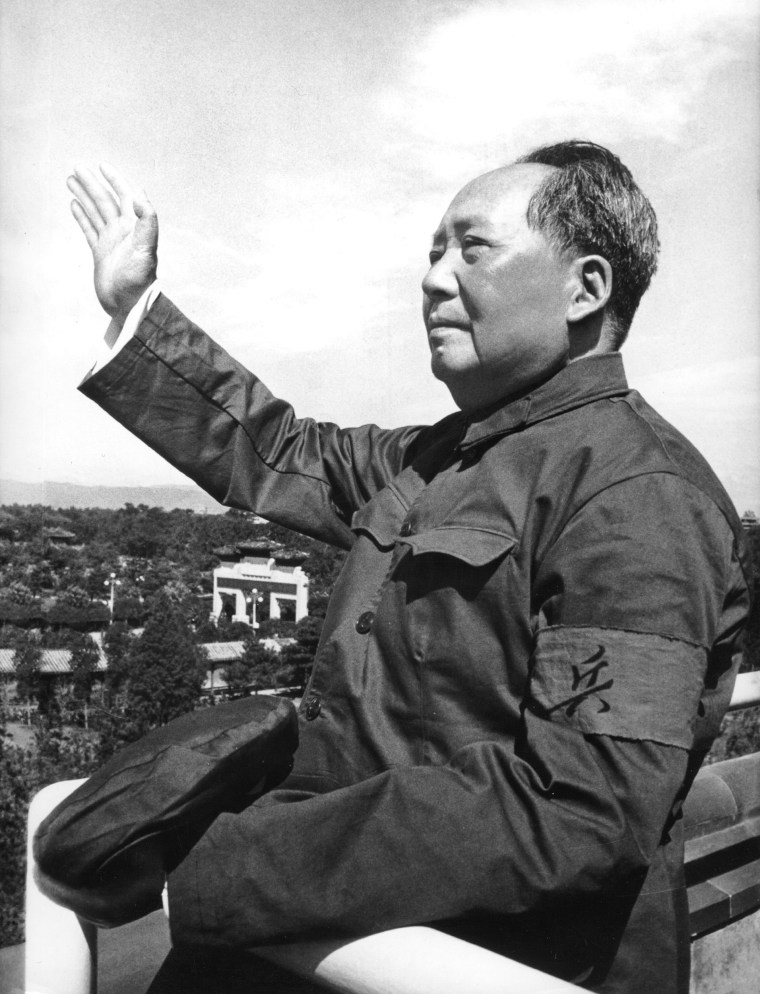

BEIJING — The crowd packed into Tiananmen Square roared and raised their fists as Communist China’s founding father strode onto the stage in the summer of 1966, recalls Yu Xiangzhen.

“We went crazy,” the retired journalist said nearly 50 years later. “We shouted, ‘Long live Chairman Mao!’ until I lost my voice.”

Yu, who was 13 at the time, was witnessing the start of one of the most traumatic periods in China’s long history.

Mao launched what became known as the Cultural Revolution on May 16, 1966. He sought to "purify" the country of capitalists, non-believers and anyone who questioned the preeminence of his own ideology.

He called on the working class to rise up against “representatives of the bourgeoisie,” triggering a decade of upheaval that saw real or imagined enemies persecuted and driven from their homes and jobs. Millions more were uprooted from cities and sent to the countryside to work, and the economy contracted dramatically.

There is no official death toll for the 10-year period, but scholars Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals wrote in "Mao’s Last Revolution" that 1.5 million people died of hunger, torture, execution and suicide in rural China alone. A similar number were permanently maimed, they estimated.

“China was like a madhouse,” prominent Beijing-based historian Zhang Lifan told NBC News. "Mao Zedong should take most of the responsibility but it was a collective crime — all of China should clean the residue of the Cultural Revolution."

Related: Mao Zedong Gets Hero Treatment in Home Village of Shaoshan

Yu, the former journalist, was a member of Red Guard student mobs that fomented violence in many schools. At Mao's bidding, children turned on parents and teachers, and parts of the country descended into anarchy.

Meanwhile, Mao cultivated his own personality cult and the so-called Gang of Four coalition around him purged their rivals from power. The nationwide turmoil only ended when Mao died in 1976 and his allies were overthrown.

For decades, Yu reflected on her role in the tumult. In 1990, she and some of her childhood classmates apologized to a teacher they had persecuted. Their apology was accepted.

But she has only recently begun writing about the pain and destruction Mao unleashed. Yu hopes breaking the collective silence that still surrounds the period will help ensure nothing like it happens again.

“There is little time left for any of us to speak out,” the 63-year-old told NBC News.

"It’s impossible to build another god"

But the Cultural Revolution is still a sore subject and the government rarely refers to the period most Chinese call the “ten years of chaos.”

A 1981 Communist Party directive saying the decade represented "the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the party, the country, and the people" is the only official acknowledgement that "serious mistakes" were made during the decade.

According to Zhang, the historian, any official introspection similar to South Africa's post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission risks appearing to criticize Mao and the legitimacy of the Communist Party.

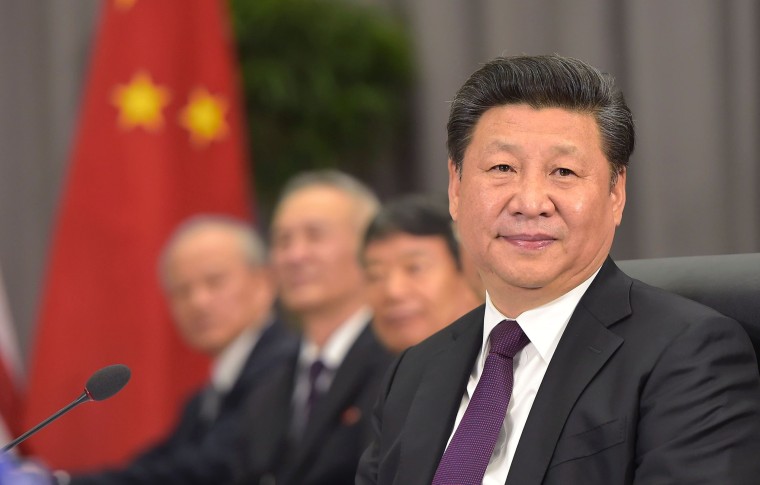

It is particularly tricky to mark the anniversary given parallels being drawn between Mao’s era and the political fervor swirling around current president, Xi Jinping.

Since coming to power in 2012, Xi has unleashed a war against corrupt officials. The government has tightened controls on free speech, jailed hundreds of lawyers, and paraded journalists accused of dissent on television. Earlier in May, the Party imposed strict new laws that may prevent foreign-backed charities from working in China.

Xi has cultivated his own cult of personality, and a raft of fawning songs and videos have been produced, including “Uncle Xi in Love with Mama Peng” by his famous folksinger wife, Peng Liyuan.

Xi has more officials titles and more power than any Chinese leader since Mao, but that should not imply he is replicating his predecessor, Zhang cautioned.

“Xi experienced the Cultural Revolution so it’s inevitable for him to be influenced by Mao’s ideology,” he said. "But it’s impossible for him to become another Mao. It’s impossible to build another god. He is destined to fail if he wants to be another Mao Zedong.”

Related: China's President Orders Millions to Read Old Mao Report

A controversial concert in Beijing revealed the government’s sensitivity to any comparisons. The Maoist revival of sorts held at the Great Hall of the People on May 2 featured a performance of “Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman,” an anthem to the Cultural Revolution.

“The Helmsman” is a nickname for Mao.

The show did not have official backing, according a flurry of articles in state-run newspapers. An editorial in the Global Times told readers the Party admitted to “mistakes” during the Cultural Revolution that “will continue to be the foundation for our understanding of that chaotic movement.”

While the Cultural Revolution may be widely seen as a troubled time, Mao himself is still revered around the country. At more than 200 so-called Red Army primary schools, students wear uniforms similar to those revolutionary fighters did in order to "inherit the red gene," according to one teacher.

Jia Jiyu, who sold clothing and accessories until he retired a few years ago, is one of the country's remaining true believers.

“Everything has its cost,” the 73-year-old Beijing resident told NBC News. "This revolution was unprecedented and a real innovation. How could it not have any cost?”

In 1966, Jia was a Red Guard leader invited to meet Mao at a rally. His embossed invitation is preserved in a cookie tin with other mementos including a pamphlet of Mao slogans and a framed photo of the leader.

“Mao turned and looked at me for several seconds,” Jia said. “It is a moment I will not forget forever.”