SAN JOSE, California – Throughout his childhood and adolescence, figure skating was a way for Rudy Galindo to escape his hardscrabble upbringing and dysfunctional home life. As a young man, he medaled in national and world championships, becoming America’s most decorated Latino figure skater and a pioneer for LGBT athletes. Now with the eyes of the world on the skating events at the Pyeongchang Olympics, Galindo is still making his mark on the sport he loves, coaching and nurturing a new generation of hopeful skating champions.

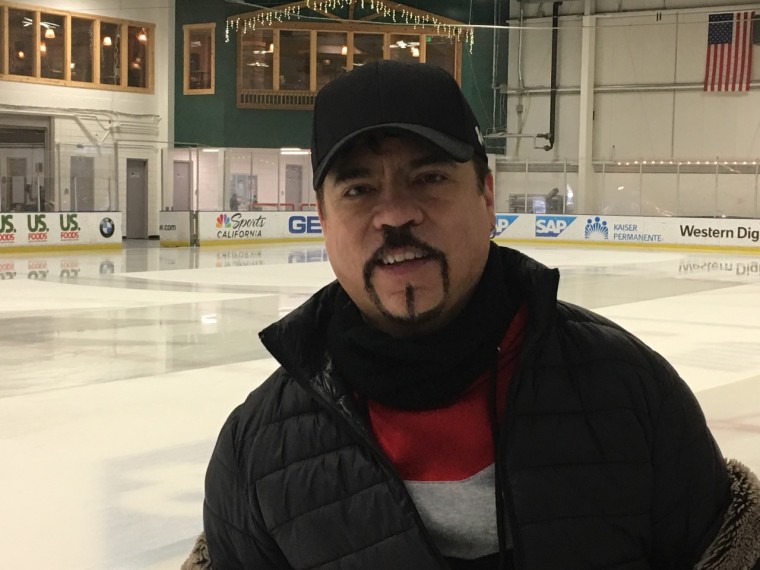

At 7:30 in the morning at the cavernous Solar4America Ice at San Jose complex, Galindo, 48, has already been on the ice for several hours. Swathed in a heavy parka and a thick scarf, he watches one of his students practice her moves.

“We have to work on your axel, those are big points,” he calls out. “Good! Now do one more!” As a dozen skaters practice their routines, the frosty air is filled with the sound of blades skimming over the ice.

Galindo raises his voice so his young charge can hear him. “Hey, why are you looking down at the ice? Don’t look down, there’s nothing down there for you!”

His student skates over for a swig of water. “Very nice, high five! Now go back and do the footwork at the end.” Galindo eyes the skater’s ponytail with a sly smile. “Hey, why are you wearing a scrunchie?! That’s very ‘80s!”

While coaching is the latest chapter in Galindo’s life, over the years he has experienced spectacular professional highs and devastating personal lows. His life story of joy, heartbreak, and triumph over adversity is legendary in the skating world.

Of Mexican-American descent, Galindo was born in the working-class neighborhood of East San Jose. His childhood was far from idyllic. His family lived in a trailer, his truck driver father was on the road for long stretches and his mother suffered from bouts of mental illness. Galindo found his escape on the ice, where his older sister was taking skating lessons at a local rink. Before long, Rudy was taking lessons too, and participating in local competitions.

His aptitude for skating came at great cost. “My dad gave everything, his whole paycheck, so my sister and I could have skating lessons and stay off the streets,” Galindo said. “He worked hard, and we never could afford to move into a house because all of his earnings went for our lessons.”

Before long, Galindo was paired up with another promising young skater from the Bay Area, Kristi Yamaguchi. “I was 11, and he was 13. He was very energetic, even at that young age,” Yamaguchi told NBC Latino. “Once we started skating together, things took off, and he was so creative. We would choreograph our own programs, and he was always full of ideas.”

Galindo even lived with Yamaguchi’s family for several years so that they could focus on their training; a typical day found them training for 6 to 8 hours, and doing their homework in the backseat of Kristi’s mother’s car as she drove them to practice sessions. “Rudy was like my brother,” Yamaguchi recalled.

As a duo, Galindo and Yamaguchi won the U.S National Championships (Junior Pairs) in 1986, the World Junior Championships in 1988, and the U.S. National Championships in 1989 and 1990. But soon Yamaguchi, who had been juggling both pairs and solo skating, decided to concentrate on her solo efforts. Her professional break with Galindo left him devastated and unfocused.

“That was a tough time for him,” said Ann Killion, sports columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle. “Rudy kind of got left behind, and Kristi was moving into her own spotlight, and then on to the Olympics.” His sense of loss was compounded by his father’s passing, and the deaths of two of his coaches and his older brother from HIV/AIDS.

After an uneven period as a skater — during which time he considered quitting the sport altogether — Galindo pulled off a surprise victory at the 1996 U.S. National Championships, which were held in his hometown of San Jose.

“I’ve been going to that arena since it opened, for sporting events and concerts,” said Killion, “and that was the most spine-tingling moment I have ever seen there.”

Coached by his sister Laura, at 26 Galindo became the oldest men’s champion in 70 years. A New York Times report described it as “one of the greatest upsets ever accomplished in American skating.”

“I think one reason why he skated with such joy and freedom that night,” Killion said, “was because he had already been through so much. It seemed like he was happy with who he was, and he was energized by skating in his hometown.”

Before winning the national championship, Galindo had come out publicly as gay — a bold move at the time in a sport that is still fairly conservative. “I guess I was ahead of my time,” Galindo said. “But I wanted to be me, to be out of the box, to be over the top, and some judges back then, well, they wanted a certain type of skater.”

According to Cyd Ziegler, co-founder of OutSports.com, Galindo was a pioneer for LGBT athletes. “Rudy being a trailblazer for other athletes, and on social justice issues, is paramount to his legacy,” he said, noting that Galindo is one of the few athletes to come out while still active in his sport.

“Some athletes don’t want to come out because they don’t want to be known as ‘the gay football player,’ or ‘the gay basketball player.’ The fact that Rudy was willing to take on this mantle is a powerful statement about him as a human being,” said Ziegler.

In his view, Galindo paved the way for out Olympic skaters Johnny Weir and Adam Rippon, and skier Gus Kenworthy, by forcing the sports world to acknowledge LGBT athletes. “Rudy’s coming out was especially courageous because, under the old scoring system, figure skating was a much more subjective sport than it is today. Judges could score him lower because they were uncomfortable with his identity.”

His titles aside, Galindo can doubly claim to rank among the U.S. figure skating elite. First, he is part of a legacy of Bay Area skaters, including Peggy Fleming, Brian Boitano, Debi Thomas, and Kristi Yamaguchi, that achieved great success. Second, he competed in what is widely regarded as a golden age for U.S. figure skating. Among his 1996 U.S. world teammates were Michelle Kwan, Tara Lipinski, and Todd Eldredge.

After winning the national championship, Galindo won a bronze medal in the 1996 World Championships. Then he turned professional, and spent a dozen years touring with Champions On Ice, performing everything from a crowd-pleasing tribute to the Village People to an elegiac program set to “Send In The Clowns.”

By turning pro, Galindo opted out of a shot at the Olympics, which he said was based, in part, on financial factors. “My family had sacrificed so much, and I wanted to be able to provide for them, and do wonderful things for them.”

The financial factor is one big reason, Galindo observed, that there are still few Latinos in the sport. “It is an expensive sport, with costs for training, travel, coaches, choreographers, ice time, and costumes,” he said. “I was lucky that my father gave up so much for me; I wish there were more Latino skaters because it would be really nice to see.”

Galindo released his autobiography, Icebreaker, in 1997.

In 2000, Galindo announced that he was living with HIV. “Again, this speaks to his courage and willingness to help others,” said Ziegler of OutSports.com, “especially 15 or so years ago, when there was much more stigma attached to going public than today.”

Galindo was inducted in to the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 2013. He is currently featured in a special edition of People Magazine entitled The Best of Olympic Figure Skating.

These days, Galindo stays busy with his students, who range from age 7 to 17, and include Ava Stephens, 13, who competed in the intermediate women’s division at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships last month.

“Ava really enjoys working with Rudy,” said her mother, Holly Stephens. “He’s fun, he inspires her, and he really brings out her sense of artistry. His choreography and artistic instincts are outstanding.”

Being a coach, Galindo said, is often more nerve-wracking than being a performer, because he has no control over how well his students will do when they step on the ice. “When my kids get ready to compete, sometimes I feel like I want to pass out,” he joked, “but I can’t show it.”

Galindo still has a bond with his former skating partner, Kristi Yamaguchi. He choreographed special numbers for benefit performances for her Always Dream Foundation – and he is coaching her youngest daughter, Emma, 12, on the ice as well. “My daughter loves working with him, so it’s like our lives have come full circle,” she said. “In a way, he is like an extended family member.”

“I am very proud of him,” Yamaguchi added, “because he has never been afraid to be who he was. He has always been like, this is who I am, so why pretend?”

Despite a lifetime of competing and performing for huge crowds, Galindo no longer misses those days. “I used to miss it (performing), because I liked the accolades and the applause, the ovations,” he reflected. “But it was a lot of work, going from city to city and training so hard. I was a showman, but I like my new life now. I am a showman in a different way — as a coach.”

Raul A. Reyes is an NBC Latino contributor. Follow him on Twitter at @RaulAReyes, and on Instagram at @raulareyes1.