CHICAGO — It’s Friday night and time for the “marcha de cumpleaños” (birthday march) at Mi Tierra restaurant in the Chicago neighborhood of Little Village. Waiters bring cupcakes with lit, oversized sparklers, while patrons don straw hats and, paying no attention to empty tables, snake through the dining room to a Latino beat in a conga line.

“Fiesta. Happy,” is how Mi Tierra owner Ezequiel Fuentes describes the good times in culturally vibrant and economically vital Little Village — or as the community calls it, La Villita, a historic section in southwest Chicago that is billed as the Mexico of the Midwest.

But since the start of the year, fear of President Donald Trump has been spoiling the “fiesta” of Little Village, business owners and regular visitors said. Despite Chicago's sanctuary city status, the uncertainty of when or whether immigration agents might strike is sapping the bustle from the 2½-mile stretch of quinceañera shops, restaurants, shoe and clothing stores, dental offices and other businesses that line W. 26th Street, the community’s main drive.

Locals say they see evidence that something has changed since January. Dozens of carved, brightly painted chairs and tables of Mi Tierra’s second dining room sat empty one weekend last month. Some tables in the main dining area also were unused. At lunchtime, half of the tables hid behind a partition awaiting customers.

“After the elections, everything changed,” said Fuentes, a former undocumented immigrant who now owns several restaurants in four states. “People are scared. They are scared to go out. The decrease of business (after the election) probably was 40 percent during the week, especially in the day time.”

Other business owners echo this sentiment. Vendors on the street corners complain that they no longer see the crowds walking up and down the neighborhood's main street and lining up at their carts to buy their "elote" (Mexican grilled corn) and raspados (shaved ice sweetened with natural syrups). The usual buzz amid the selling of mariachi suits, clothing, jewelry, curios, accordions and many other goods at the Discount Mall outside Little Village's welcoming arch is dampened.

Business leaders have been trying to tamp down the fear they think is driving the slowdown, reminding the community of Chicago’s historic sanctuary city status, and enlisting the mayor and police chief to dispel anxieties. They tell them there are no arrests going on in the neighborhood, that the Chicago police and local agencies don't cooperate with the feds or question the immigration or citizenship status of residents because Chicago is a sanctuary city.

Exuding confidence in the city's sanctuary status has taken on an urgency as news stories of arrests of immigrants with DACA - a type of protection from deportation - and people with immigration violations but not criminal histories fill the national news. The administration has threatened to punish cities that don't cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“I would tell people here in La Villita to not be afraid, to get well informed, find [out] for each other if ICE is coming. Get communication through police. Come out and support our families, our businesses,” said Ezequiel Fuentes Jr., who works with his father in running their restaurants. “La Villita is a great place. We can make it even greater.”

Two days after the Mi Tierra celebration, residents came together at La Villita for a community meeting where some of the topics discussed included how to prepare for possible deportation, what rights people have if arrested and shopping local. The meeting’s title: “La Villita Se Defiende.” (“Little Village Defends Itself.”)

Fear In a Sanctuary City

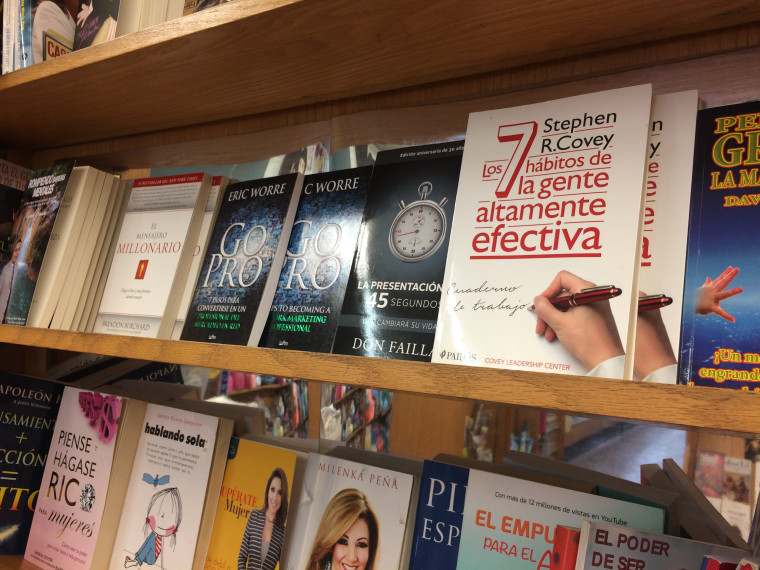

Librería Girón, a bookstore in the heart of Little Village owned by Patty Girón García and her family, also is experiencing a slowdown. The 50 customers a day who used to come to buy her books, statues of saints and Frida Kahlo T-shirts trickle in now and have her worried about being able to pay her own bills and her employees.

“People aren’t coming in as they used to come. Yesterday was so quiet and you’re like, ‘What’s going on? What’s wrong? What’s happening?' I think they are afraid.”

Her mother and father, originally from Guatemala, started their book and music store business in 1957, expanding to nine stores a couple of decades ago. The family’s two remaining stores operate in Pilsen, another Latino neighborhood, and Little Village.

In the Little Village store, the shelves are filled with titles in Spanish, but many are translations of those found in English. She once stocked the book Trump co-authored with Robert Kiyosaki, "Why We Want You To Be Rich," the Spanish language version. A customer told her to burn it, but it eventually sold and she doesn't plan to stock more.

Girón encourages patrons to learn English and stocks citizenship test preparation guides. She acts as something of a community librarian, answering customers' questions on where to find resources in the city.

“We depend on the community and I think they depend on us,” Girón said.

Even so, the reduced traffic has forced her to open later and close earlier. In her personal life, she’s watching her own purchases and “downsizing.”

“What’s my future also going to be? I don’t know. Will I be here in 10 more years. It’s been 60 years. My parents worked a lot to be here. My brothers too," Girón said.

'Mexicans Turned Around Little Village'

Immigrants — German, Irish, Czech, Polish, Latino — have been Little Village’s lifeblood for more than a century. The community was originally founded in 1871 as South Lawndale. Immigrants have helped keep Little Village alive and Chicago from going the way of Detroit, said Andrew Sandoval-Strausz, who is writing a book about the historic neighborhood.

“That was really a declining part of the city until the Mexicans moved in” around the 1960s, Sandoval-Strausz said. Little Village had been on a 40-year-slide when Mexican immigrants arrived.

“The Polish and Czech Americans were moving out to the suburbs and there was a lot of houses going empty and unsold and the Mexican immigrants were only thing that allowed it to come back. Mexicans are the ones who turned Little Village around,” Sandoval-Strausz said.

Business leaders and others regularly and proudly mention that Little Village is Chicago’s second largest commercial strip, only trailing the city’s upscale Magnificent Mile.

“La Villita is the mecca of the Mexican entrepreneurs of Chicago and the Midwest. There’s over 1,000 businesses here and most of them are immigrant owned businesses and that’s where we start our American Dream right here,” said Jaime Di Paola, Little Village Chamber of Commerce executive director.

Di Paola said people in the community range from long-established Mexican Americans with generations of families who are citizens, to the more recently arrived. About 15 percent are undocumented and about three quarters of the businesses are immigrant owned, he said.

The American Dream is how Eve Rodriguez Montoya describes her family’s business, Dulcelandia, which sells a cornucopia of Mexican candies, piñatas and her latest product, healthy frozen yogurt with Mexican flavors such as arroz con leche (Mexican rice pudding), churro and café de olla.

Her father founded the business 22 years ago, after arriving in the country at age 13 and starting out with an import-export business.

Rodriguez Montoya said her business hasn’t suffered and sales actually have been up. She acknowledged other businesses may not be doing as well, but she blamed the weather and a natural drop in sales in winter months.

“The conversation naturally is scary and people are reacting to it and I also see a lot of false information to it,” Rodriguez Montoya said.

But Guadalupe "Lupillo" Perez, a raspador who owns five carts situated around Little Village to sell raspas, dismissed the possibility that other factors might be at fault. He blames Trump.

"He’s a businessman not a politician… because if he was a politician he’d think differently. Think about it ... if he were to send all the Latinos to their countries, imagine what the United States would be like?"

Little Village draws not only Latinos from Chicago — many of them Mexican or Mexican American — but also from Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana and other parts of Illinois. One group of men who had heard about the neighborhood from other Latinos had arrived from Kansas, setting out to Little Village at 4 a.m.

Some of the business owners suggested that the out-of-towners are forgoing the drive because while Chicago may welcome its immigrants, other places on their route may not.

Saving for Deportation

It’s not only fear, locals said, but cautiousness and preparing for the worst that is affecting Little Village.

Mario, who did not want his full name used because he’s undocumented, said he wants to have about $10,000 saved to take with him to Mexico if he’s deported.

He and his wife, who is a U.S. citizen, usually use their income tax return to buy supplies at Home Depot or other hardware stores for a home project. In the past, they’ve fixed the boiler and renovated the kitchen. This year they have decided to save the money.

“We can’t take the kitchen to Mexico with us if anything happens,” he said.

Ariella Santoyo, one of the owners of Recuerdos, a full service quinceañera shop that sells dresses, photos, clothing for attendants and organizes limos, has heard similar stories from customers. The dresses and other items are a luxury that in these times can be put on hold, she said.

Recently, a customer who had planned to splurge on all the quinceañera-related items ended up only buying the daughter's dress, Santoyo said.

“I'm like, 'Really?," said Santoyo. "And she’s like, ‘Because I can take the dress with me and do the quinceañera in Mexico.'"

"We Have to Keep Going"

Despite the slowdown, families and consumers who can are still turning out for Little Village's specialties.

Marisol and Omar Martinez of Wisconsin were in the community recently shopping for a quinceañera dress for their goddaughter. Marisol Martinez, who has DACA, said rumors are keeping people in fear and making people more cautious. Still, life goes on.

"We have to keep going," she said. "We can't stay hidden and stagnant."

Business owners explained that Little Village's economic well-being spreads beyond their community.

Rodriguez Montoya starts out Dulcelandia's Mexican-flavored yogurt with a base yogurt that is made in Arkansas. She also stocks her candy store with a variety of American-made candy brands.

Santoyo said the suppliers for her one-stop quinceañera shop are U.S. businesses. Girón said about half of her bookstore's stock comes from the U.S. and the other half from Mexico.

It is because a steady supply of immigrants have filtered into Chicago's communities, including Little Village, that the city has not been stagnant, Sandoval Strausz said. The area of Little Village was shrinking every bit as fast as Detroit until the Mexican immigrants arrived.

"Cities like Chicago and L.A. and and plenty of others, Dallas too," he said, "are dependent on immigrants."

Video story by NBC Latino's Marissa Armas.