NEW YORK, NY — For over five decades, Cuba and the United States have been separated by an embargo. But one Cuban science fiction writer is crossing over political, economic and cultural walls to show readers how both countries share a common origin.

“I think we sometimes look for enemies in people who are distant or different,” said award-winning author José Miguel Sánchez Gómez (better known by his pen name Yoss), who is on tour during October and November promoting his books in the U.S.

“But deep down inside, an enemy could just be a friend, a neighbor who emigrated to another place. And we need to remember how we are all citizens of the same planet.”

As the nation celebrates Columbus Day—and others reflect on the negative consequences that this encounter had on indigenous peoples—Yoss said that the story of early Spanish-speaking communities coexisting in the Lower East Side of New York could offer Latinos (and Cubans in his homeland) a lifelong lesson about their mixed heritage.

Dressed in urban combat fatigues and a muscle shirt, Yoss looks like Snake Plissken, the cult antihero from John Carpenter’s classic 1981 movie “Escape From New York.” Played by actor Kurt Russell, Plissken is a former special forces soldier turned criminal who enters Manhattan, which has been transformed into a maximum-security prison surrounded by 50-foot containment walls. And Yoss similarly challenges both Cubans and Americans to climb over the political and cultural walls that separate their homes from other places.

RELATED: Our 'Super Extra Grande' Talk with Cuban Science-Fiction Novelist Yoss

Yoss walked with us around an area rich in history and culture. Squeezed between the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges on the Lower East Side, tourists and New Yorkers alike can find the stories of different immigrant communities who lived in close proximity during many generations.

This coexistence between Cubans, Spaniards, Jews, Chinese, and other groups, Yoss explained, shows how beneath everyone’s differences is a universal immigrant heritage that connects the whole planet.

“Remembering how Cubans were welcomed to New York [with other immigrants] even before the Statue of Liberty existed teaches us an important lesson about coexistence,” said Yoss. “To be Cuban, like any other nationality, is a state of mind. And to be an immigrant is much more complex than the religions, flags and languages that divide us. Immigrants have to connect with different people to survive.”

RELATED: Through Program, Cuban American Millennials Visit Island for 1st Time

The first wave of Cuban immigrants settled in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Brooklyn and other parts of New York City in the 1870’s and 1880’s. These exiles escaped ongoing violence and repression during Cuba’s fight for independence from Spain.

Many Cuban immigrants were Catholic, and migrated north to work in cigar factories opened by other Cubans—and Spanish immigrants—in Key West, Tampa and New York. The most popular immigrant from this community was the legendary poet and independence leader José Martí—honored with a statue in Central Park—who worked tirelessly from New York to end slavery in Cuba and recruit supporters for independence.

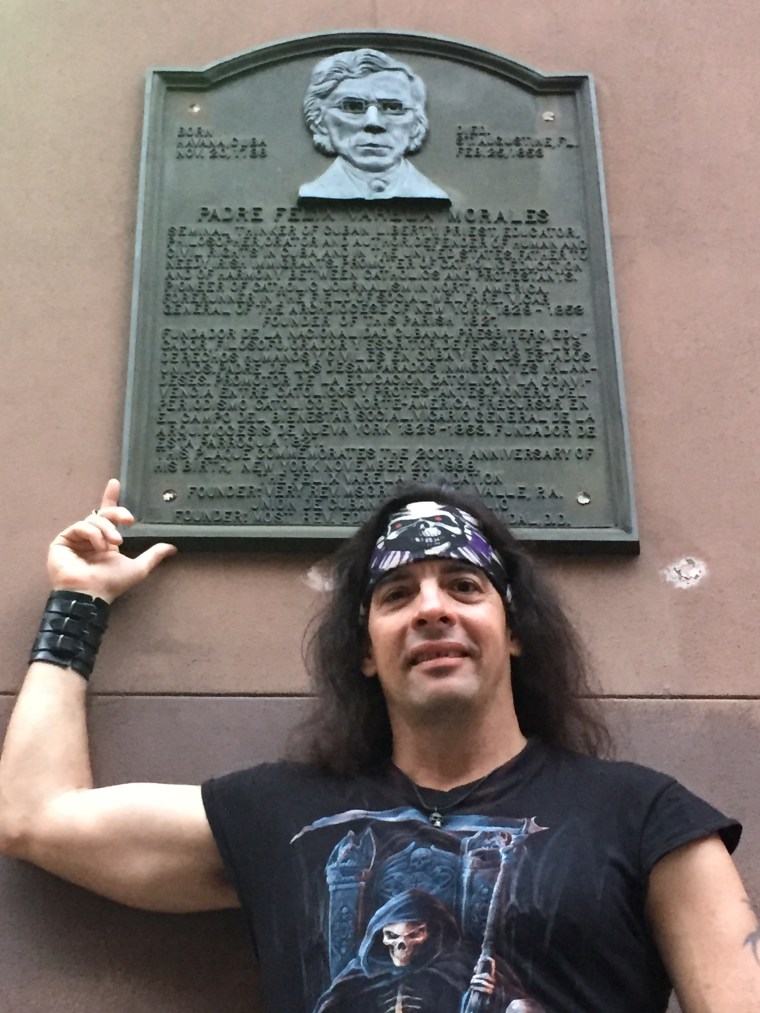

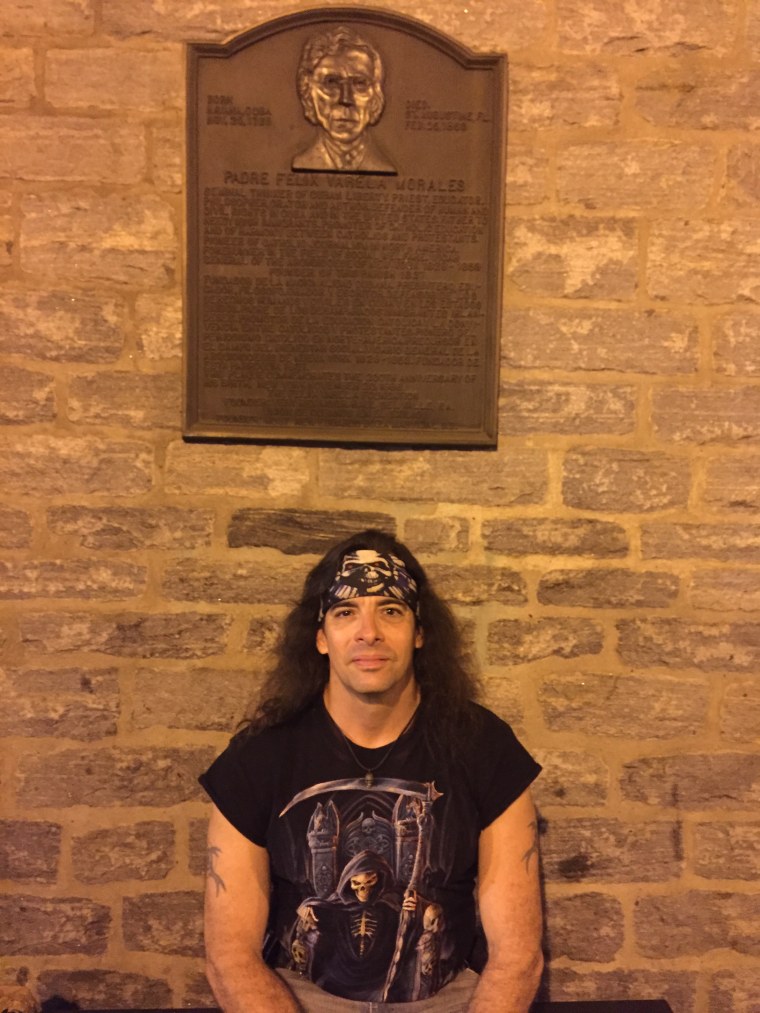

What draws Yoss to the Lower East Side in Manhattan, however, is not the story of Cuba’s “father of independence”, but a thin Catholic priest who “taught [Martí] how to think.”

Chronologically, Father Félix Varela was not the first Cuban immigrant to settle in New York City, but he planted the seeds for the Cuban independence movement in Manhattan and helped organize the Catholic Church to stand up against nativists and defend immigrant rights as early as the 1820s.

RELATED: Like Science Fiction? Cuba's Best Writers Now Published In English

Varela’s immigrant story begins in 1821, when he travels to Spain as a Cuban representative to petition for Latin American independence. But soon after King Ferdinand VII suppresses Spain’s liberal government, the monarch sentences Varela to death. And the priest-turned-fugitive narrowly escapes to New York on a cargo ship, where he continues to demand Cuban independence from exile, and writes many articles defending human rights and religious tolerance.

At times, Varela’s extraordinary immigrant biography reads like a cloak and dagger story. While more than 1,300 miles separate Cuba from Manhattan, the priest’s persecution does not end. Spanish police in Havana dispatch a hit man to murder Varela in the Lower East Side. But loyal Irish parishioners quickly rally to protect the Cuban, driving out el tuerto (the one-eyed) thug from New York before he could carry out the 30,000-peso assassination contract.

As the Vicar General of the Diocese of New York, Varela had become an important leader in the Irish Catholic community—even learning Gaelic to better serve the influx of new parishioners.

RELATED: How A 19th Century Cuban Immigrant Became A Countess And Author

This ability to cross over between languages and cultures, Yoss pointed out, is part of the enduring legacy of many immigrants from the Lower East Side, where the roots of early Spanish-speaking communities were planted.

Just around the corner from St. James Church—purchased by Varela in 1835—is the first Spanish and Portuguese Sephardic Jewish cemetery—founded by Jewish immigrants who settled in New Amsterdam in 1654.

Around the other corner on Madison Street, where the Alfred E.Smith Houses now stand, was Roosevelt Street—the heart of the Spanish immigrant community in the 1910s and 1920s. And across the street from Varela’s church was St. James parochial school, which educated many generations of Catholics in the city, including Al Smith—the first Catholic nominee for the U.S. presidency.

“Independently from our local accents, colloquial expressions, the Spanish language is neutral, multinational, and can teach us how to live beyond politics and borders,” said Yoss.

And centuries later, the buildings and streets in lower Manhattan that continuously absorb new generations from all over the world tell a story of the Big Apple's Spanish-speaking presence.

“History happens whether it is politically convenient or not. And while politics and governments change, history will last forever.”