Where have all the children of Puerto Rico gone?

The island, which is already battling a long-running financial crisis, high unemployment, increasing migration, and the devastation caused by the deadly Hurricane Maria, also faces a dramatically dwindling population of young children and working age adults.

The number of children under 5 years old fell from 251,000 in 2006 — when the island’s fiscal crisis began — to 146,000 in 2017, a 42 percent decline, according to a report released Tuesday by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York City.

Meanwhile, the numbers of school-age children dropped 30 percent, from 883,000 to 609,000.

“Where are the Puerto Rican babies? They are all in the diaspora,” Centro’s director Edwin Meléndez told NBC News.

Puerto Rico was experiencing a population decline largely driven by migration and low birth rates before it was hit by Maria in September 2017. Since the hurricane, migration has intensified, particularly among adults with children, researchers said.

Puerto Rico's population was about 3.9 million in 2009. That compares to about 3.1 million in 2018, according to the latest Census Bureau estimates.

The researchers are urging Puerto Rico’s government to develop a broader plan beyond school closings to deal with the falling numbers of young children and working age adults.

Demographer Alejandro Macarrón has said the island is undergoing a “demographic winter” in which fertility levels are low — below two children per woman, as migration from the island to the mainland United States continues, and deaths on the island exceed births.

“We don’t expect this to stop any time soon,” Meléndez said.

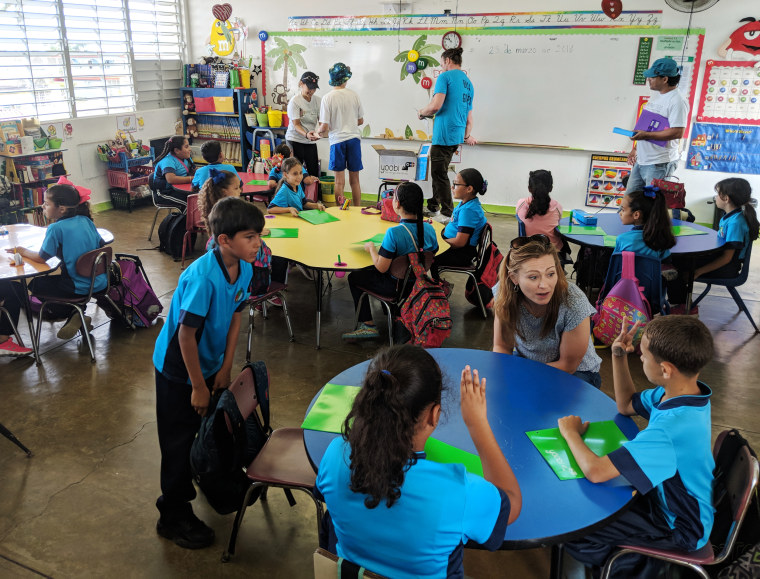

The population declines have led to increasing housing vacancies, lower growth rates in child populations and closings of 265 public schools — a 24 percent drop — throughout the island. In the 2018-19 school year, 855 schools remained open, down from a peak of 1,515 in 2006.

But school closings have fallen disproportionately on the island’s rural areas, which have absorbed 65 percent of the closings compared to 35 percent in urban areas.

“The question is, how do we make the closings of schools more rational so that we attend to the needs of rural communities, and closings are not just based on considerations of costs and participation?” Meléndez said.

Before the start of this school year, the Puerto Rico government shuttered dozens of schools, triggering street protests by teachers and organizing by parents.

Anger deepened when Gov. Ricardo Rosselló signed a law allowing publicly funded, independently run charter schools, and vouchers for use in private schools.

“Communities are opposing school closings because they know what the impact to kids is,” Meléndez said.

Meléndez and his coauthors in the report recommended that the island’s government rethink how it is closing schools and take a more holistic approach that also considers other demographic change.

The narrative must move beyond school closings and austerity measures, he said.

“We need a more holistic and comprehensive focus in order to appropriately respond to these trends and consequences,” Meléndez said in a news release.

The researchers urged Puerto Rico’s leaders to come up with a master plan for schools, use shuttered schools for distance and adult education, or transform them into community centers or “resiliency” centers for future hurricanes and other climate-related issues.

Montessori schools also are emerging as a potential solution because they are public, allow for combining grade levels, and are educational programs that might attract parents from other parts of the island to areas that want to increase their population, he said.

Good schools also may help draw back Puerto Ricans who have left the island, he said.

“This is a conversation about the future of Puerto Rico — what kind of country we want,” Meléndez said. “Are costs the only factors that should drive the conversation?”

FOLLOW NBC LATINO ON FACEBOOK, TWITTER AND INSTAGRAM