BOLIVAR, MISSOURI -- On July 5th, 1948, the drum majorette forgot about the soupy Missour-ah humidity: who could think about that when you were watching North and South America shake hands?

The presidents of the United States and Venezuela had traveled to the heart of the American Heartland—Bolivar, Missouri—to honor the largest U.S. town named for the Venezuelan liberator Simon Bolivar. The illustrious Latin American general had swept across South America in the 1830s to liberate it from the Spanish: from Colombia to Venezuela, Ecuador to Peru.

Settlers moving across the American frontier in the early nineteenth century named a slew of their settlements “Bolivar” in admiration of his liberating spirit. Little did they know that their outpost in the Ozarks would one day host the 1948 commemorative Simon Bolivar statue from the Venezuelan government.

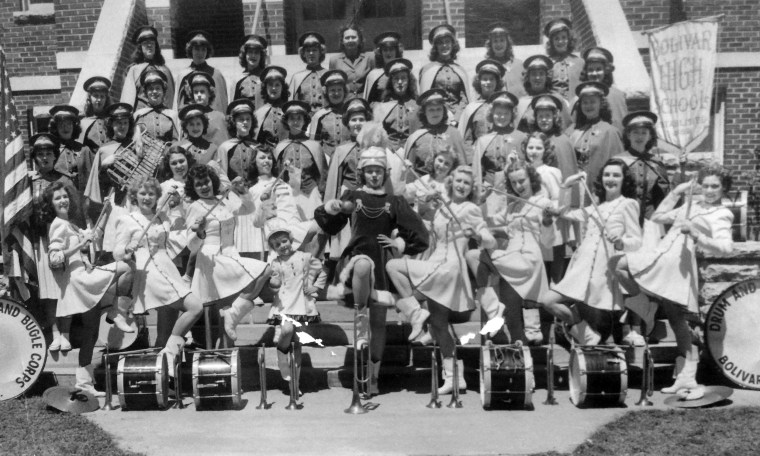

So on July 5th, 1948, the drum majorette worked to fend off the ninety-degree heat with the event's glossy heavyweight program, while a transatlantic handshake brought history to the sleepy backwoods of the Midwest. Now, at her serene kitchen table scattered with newspaper articles and photos, she remembers the historic aspect of that moment. My grandmother smiles softly with understated pride as she points to a baton-twirling young girl in a white drum majorette costume, with gold braiding and matching boots.

“It was the biggest thing that had ever happened in Bolivar.”

I am Bolivian in every sense of the word. I am ethnically half Bolivian—Bolivar’s namesake country—and I was raised in the homogeneously white city of Bolivar, Missouri. My Missourian grandmother, Carolyn Roberts, is a matriarch of the town. I never experienced discrimination or felt my Bolivian father was any different than anyone else’s father. Yes, I look white, but in a place where everyone knows your name and heritage, I never felt any degree of separation.

Last year NPR published a report on the racially charged history of the Ozarks. It is an uncontestable one. Linda Brown graduated from my high school after transferring from the Little Rock school she famously desegregated. How could this past be reconciled with my modern life experiences: a Latina who felt accepted in a 98 percent white community, who went to a high school boasting over 30 nationalities?

“I’m sure everybody that could walk turned out for it in Bolivar.”

“I’m sure everybody that could walk turned out for it in Bolivar,” my grandmother remembers.

Fifty thousand onlookers packed into the small town of 3,500 people that grew up on the juncture of Highway 13 and Highway 32.

Over the three-day weekend of July 4th, Independence Day is celebrated in both the United States and Venezuela: ours is on the 4th, Venezuela’s on the 5th. For the Washington Committee of Americans and Venezuelans planning the event, there seemed no better time to honor the ideological connection they found in the South American Liberator.

“They had a platform on the north side of the square, and that was the reviewing stand,” my grandmother remembers. Newspaper accounts confirm that Presidents Harry S. Truman and Romulo Gallegos left their special trains that morning around 9:00AM and rode in top-down convertibles to the reviewing stand. President Gallegos was the first elected leader of his country.

“We were very proud to be marching in the parade, even as hot as it was,” my grandmother recalls. She says that several spectators had to be treated for heat-related issues in first-aid stations. Even President Truman felt it; at the reception on the lawn of the local Baptist university later that afternoon, the drum majorette remembers that he did not eat because the heat had smothered his appetite.

Now, amidst the sprawl of paper-and-ink memories, I wonder what it all meant. Is the Bolivar connection only in name? Well, my grandmother says the town did change its high school mascot to the “Liberators” after the 1948 event. But has the title percolated through the culture? Where were the ethnic descendants of the South Americans liberated by Bolivar—besides myself?

“Everywhere I go, I know them.”

Gabriela Glendenning, 46, came to Bolivar in the trunk of a car. She was fleeing from Mexico with her two children; she came at her brother’s request to help him run the restaurant “Tacos.”

“I thought we were going to die in the trunk because there wasn’t air to breathe,” she remembers. As border control methodically checked every car, she says she prayed. “I prayed God, if the U.S. is for me and my kids, let us go. If no, then I will be happy to be in Mexico.”

Now, you might catch a glimpse of Gabriela at Brenda’s breakfast place, or at the First Assembly of God Church, or cheering her son on in a Bolivar High School soccer game. “Maybe 80 percent of people in Bolivar, I know. And everywhere I go, I know them, and they hug me, and they know my kids,” she says in patiently slow English.

Gabriela did not speak a word of English when she came to the U.S. at 34. But now twelve years later, we speak in English on the phone for an hour and a half before a friend, Tony Brown comes over, who helps translate only a few final questions.

“It’s a small community, but they [Hispanic people] are integrated into the whole community,” says another friend of Gabriela’s, Natalie Wolf. “I have not seen any fracture, and nobody that I’m associated with has ever said anything against a minority.”

Gabriela says that “Latin” people in Bolivar do not really have a separate community of their own. Many of them are owners or workers in the town’s three Mexican restaurants, as she was once. But in general, she says, Latino and white people go to church, school, and soccer games together.

Natalie says she helped Gabriela pick out her wedding invitations last summer. “I would do just about anything for her. And I think she would do about anything for me.”

Natalie first met Gabriela when she came to clean her house; hers is one of 35 houses Gabriela cleans as part of her own cleaning business. “We’ve kept her all this time, and she and I have become really close friends. I think she’s definitely part of the community,” says Natalie.

Here in the heart of the Midwest, an undocumented immigrant is the last woman one would expect to feel integrated and welcomed into a rural community. Bolivar is one of the most racially homogenous towns in this predominantly Caucasian area: 98 percent white. And yet, Gabriela, her family, and friends tell a story of integration, not discrimination.

“I love Bolivar,” Gabriela says. “It’s my town.”

“She came here with nothing.”

The Gabriela of 2014 is very different from the woman who walked into her brother’s “Tacos” restaurant in 2002. She and her boyfriend had sold everything to get visa papers, then they were denied. Her boyfriend almost died in the desert trying to cross the border before the family finally stowed away in the trunk of a car. She believes God brought her and other Latinos to Bolivar for a reason. “I open doors for people to show that we [Mexican people] want to work hard and build a better life for our kids. We pay our taxes.” She thinks she may die in Bolivar and never return to Mexico.

But staying in Bolivar was anything but easy. In 2005, there was an immigration raid in her brother’s restaurant. Her brother disappeared and she has not heard from him since. Gabriela went within the hour to marry her new American boyfriend at the courthouse, but still had to spend two days in jail. By 2007, her husband had become abusive, and she was on the cusp of being deported to “get her papers and then return,” she says.

Then, a Bolivar attorney told her that, as a victim of domestic violence, she could get a green card to stay in the States. Now, six years later, she has remarried into a prominent Bolivar family and is running her cleaning business. She says it was the “wedding of her dreams.”

“She came here with nothing,” her new husband says. He admires the same ideals that all four Bolivarians interviewed do: hard work, honesty, and friendliness. And he found them in his new wife. “She makes sure everybody’s paid, and if they aren’t, she’ll take another job to get them paid,” he says. “She can make a friend with anybody.”

“I have me some Mexicans.”

I asked Gabriela if she had ever had anyone discriminate against her in Bolivar. She remembered that it was difficult to get back into the community after the immigration raid. “One of the guys who used to come to Tacos with his wife—he yelled at me and said, ‘Wetback, you need to go back to your country because we pay taxes.’ It was really mean and I was crying. There were people behind me who told him to stop. The doctor’s wife—they’ve moved to Florida now, I don’t remember her last name—saw me crying and she told him to stop, because she knew how hard working I was and knew my kids.”

Her new husband, David Glendenning, says that people don’t “mouth off” in front of him; he says he's a pretty big guy. But there aren’t that many bigots in Bolivar, really.” If anything, David says, “older people don’t realize it [when they discriminate].”

After David married Gabriela, he remembers having a farming friend at the state fair say, “I have me some Mexicans," referring to the workers in his farm.

"He really did like [the] Mexicans [who worked on his farm], but it sounded wrong,” says David. Gabriela did not take offense, but he thinks somebody else could have been easily offended by the comment.

On July 5th, 1948, my grandmother watched the unveiling of a 7’1” bronze statue of Simon Bolivar. The two presidents of Venezuela and the US, whose handshake had shaken the history of these sleepy backwoods, boarded the special train home. They left behind a town with a new high school mascot, “The Liberators.”

Between the two interviews I had with Gabriela, she asked the regulars at Brenda’s breakfast if they knew what Bolivar’s name meant. “They knew he was the liberator from Venezuela and he was Latin,” she says. Her friend Natalie says that, in general, most Bolivarians don’t make the connection between their town and its namesake.

But what this community seems to be about is acceptance. “They accept all of us. They make us feel welcome,” says Gabriela. “I would tell my family that if they come, they should come to Bolivar.”

--Additional producing as well as video by Emilia Cavero.