NEW YORK -- Yadira Garcia's close relationship with food began when she fell down a flight of stairs in her junior year of college, leaving her unable to walk and in enduring pain.

The disability caused sudden spikes in her cholesterol and blood pressure, and she ended up with prescriptions for Oxycontin, Vextra and Lipitor. She said she suddenly had found herself, "a prisoner in her own body," and at 20, was told this is what her life would be. Then she lost her health insurance.

“When you’re not handed the right road map, you can’t get to your destination,” Garcia said. “So, I went back to my elders. I thought, ‘What did my grandmother eat?’ I went finding these foods. I started to eat well and started to see how my health was improving and changed. I went from a walker to a cane. It was a three to four year process – very incremental. Eventually, I got off my cholesterol medication.”

Garcia told her story to open the 2017 Just Food Conference held this week at Columbia University's Teacher College in New York City where nearly 800 food workers, farmers, scientists, activists and citizens gathered to collaborate on creating and advocating for an economically equitable, environmentally sustainable and healthy food system for all.

Now 33, Garcia is a food educator, community chef, and has her own blog, Happy. Healthy. Latina., where she posts her latest healthy recipes and answers readers’ questions. You can also check out her latest project there - a new cooking show, called “Healthy Cocina,” which is produced by actress Zoe Saldana, and also features Saldana's sister Cisely.

Garcia, who was raised in New York City but whose family hails from the Dominican Republic, said our ancestral knowledge is our power. She decided she wanted to give away the knowledge she had, and she also put herself through culinary school – the Natural Gourmet Institute in New York.

“I learned how to activate Latino foods,” she said. “I make medicinal sofrito.”

In addition to hosting cooking workshops with seniors and ex-offenders in the community, teaching them how to use food in a healthy manner, Garcia is also on mission to get nutritional education to youth by spearheading wellness classes in schools.

“I am extremely concerned about H.R. 610 – the (proposed U.S. House) bill that will affect snacks and meals in schools,” said Garcia. "I feel an urgency now to tap the community ... We train parents how to make demands. If we don’t know what’s happening, we’re silent. I talk with them to add their voice. We the people are the only ones who can make a change. We the people have to use our voice. Instead of being scared, we can talk ... There is power in numbers.”

“I think this is why I was given my ability to walk again, to be able to share my testimony,” she adds.

While eating healthy foods is a challenge for some, for others, it is getting sufficient food at all, along with getting food that is nutritionally beneficial.

Jose Chapa, 32, justice for farmworkers legislative campaign coordinator at Rural & Migrant Ministry, said food and restaurant workers are the most food insecure population – many can’t afford to feed themselves, and injury and illness rates at work are also high.

RELATED: 4 Delicious Latino Food Trends: We Asked the Chefs

“Part of what I do is try to get the Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act passed,” said Chapa, a panelist at the conference. “In the 1930’s, when the New Deal was passed, farmworkers were excluded from many rights like overtime pay, or a day of rest. The Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act would enact a 40-hour work week and an option for a day of rest. A lot of the time, the standard of living is so low, there are no sanitary requirements, no protections for farmworkers. Only recently, they were given minimum wage and access to drinking water in the fields.”

Rural & Migrant Ministry, a non-profit located in Poughkeepsie, New York, aims to change unjust working conditions for farmworkers, and will be a part of the Cesar Chavez Rally for New York State Farmworker Rights on March 30.

Chapa, born in China, Nuevo León, Mexico, feels close to this cause, because he grew up as a migrant farmworker. He migrated with his family to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas when he was 4.

“My parents wanted a better education and future for me and my brother,” said Chapa, who came to New York three years ago to fight for farmworker rights, while the rest of his family is still in Texas. “Every summer, my family would go to Iowa and Minnesota to work the fields. My family worked picking corn and cotton every summer from when I was 4.”

He said he personally worked in the fields from age 15 through 16.

“I remember conversations of my dad talking to farmers in broken English. I heard racial epithets. That impacted me,” said Chapa. “The first time I went out in the fields to work, I had a heat stroke because it was so hot. Those two things drew me to this work.”

In addition to educating the community about the bill he wishes to see passed, he also reaches out to similar organizations to collaborate. He said he tries to create a sense of community where farmworkers can gather and talk about issues they are facing – especially with the increasing fear of immigration enforcement.

“I’ve heard of more activity of border control by Buffalo,” said Chapa. “We refer folks who are fearful to other organizations depending where they are in the state. What would help a lot is the passage of this bill. We have very good speakers on our side, and we are hoping these voices can give farmworkers a voice.”

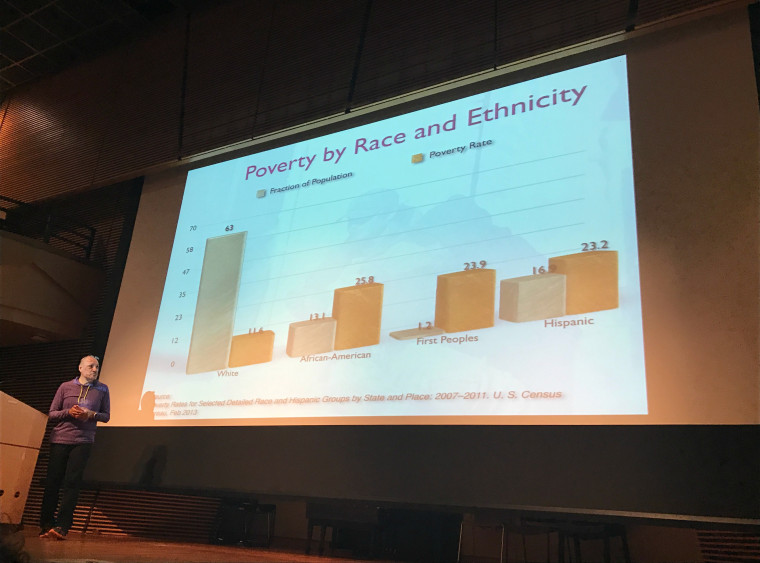

Dr. Ricardo Salvador, senior scientist and director of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, based in Washington, D.C., delivered the conference's final keynote address, “The Future of Food Justice.”

“The footprint of inequity is something I want to talk about,” said Salvador, 59. “Without a just food system, we can’t have a just nation.”

He explains that a just food system is one that doesn’t exploit food workers, and the current model is based on production for as much profit as possible. The fundamental purpose of the food system, he said, should not be one which enables us to solely survive, but one which also nourishes us.

“Profits should not the primary goal, but healthy people and animals,” said Salvador. “But this is not feasible because most people are not informed. We need to point people to places where it’s working – that is concrete and real.”

One of the ways the Union of Concerned Scientists has taken action to coordinate and align leadership is by forming The HEAL Food Alliance. The national organization was founded in 2015 to bring together farmers, food service laborers, scientists, policy experts, and community activists in order to achieve effective policy change in our nation’s food system. It does this by empowering local leadership, training future politicians in policy issues and working against monopoly power structures.

This topic is close to Salvador’s heart, because like Chapa, he comes from a Mexican farm-working family. After the 1942 agreement between the U.S. and Mexico, also called the Bracero Program, his uncle and hundreds of thousands of mostly indigenous people migrated to join the agricultural labor force in various parts of the U.S.

“This set the pattern for decades of subsequent migration and exploitation,” Salvador writes in his blog.

“I have family farming in California and in Mexico, and they were all exploited,” he said. “I felt they were discriminated against – no matter how hard they worked. That’s why my work has turned into social justice work.”

RELATED: In Cuba, Tobacco Farmers See Best Crop in Years

Salvador’s research suggests that the U.S. has one of the highest rates of income inequity in the world. Other studies also have documented this.

“This is what needs to be undone…You deprive people of their land, and you will create impoverished people,” said Salvador, noting the income equity found in some Native American reservations. "There is an exploitation of human beings for the creation of wealth.”

Salvador continues to say, if we want a society where we all thrive, we need to invest in each other.

“If we are all one race, we really need to believe it,” he said. “All of us here now are making the future. We need to be careful not to commit the same errors … You have to believe things will get better, because you fight for them. I came from people who took big risks.”