When you have to drive more than six hours to eat your favorite Latin American dish because local groceries don’t carry the ingredients to make it at home, you know you live in "Gringolandia." That is what Nery Diaz, a native of Honduras, discovered days after moving to Maine a year ago.

“Even if my wife wants to cook baleada (a traditional Honduran dish that is similar to a Mexican quesadilla) at home, we haven’t been able to find a store locally that carries the flour to prepare it,” explained Diaz, who moved from the Washington, D.C-Virginia area - the epicenter of the U.S. Central American population - to South Portland, Maine a year ago to help open a Mexican restaurant with a friend.

“I can count the number of Latinos in this state in one hand, and most work in my restaurant,” he said jokingly of the Hispanic population in Maine. But the real cultural shock for Diaz, who lives with his wife and 12-year old daughter, wasn’t that he couldn’t find an eatery that carried his favorite delicacy when the craving hit. His big culture shock involved soccer, his favorite sport.

“In my old neighborhood I could walk to almost any public park on any day of the week and pick up a game of futbol,” he explained. “Since moving here, I’ve yet to see one player kicking the ball around,” Diaz said somberly. And this is coming from a man who managed a soccer league of twenty teams.

“But it’s worth the sacrifice," he added. "There are more financial opportunities here for me and my family.”

Diaz is part of a growing number of Latino professionals who are moving from traditional Hispanic settlements to states and towns with very little Latino presence. Maine and Vermont, among the whitest states in the nation--both have less than 5 percent of Hispanic residents, combined. Yet these states have seen a six percent increase in the Hispanic population in the last decade, according to the U.S. Census.

“I can count the number of Latinos in this state in one hand, and most work in my restaurant,” said jokingly a Honduran who moved from Washington, D.C. to South Portland, Maine to open a business in the area.

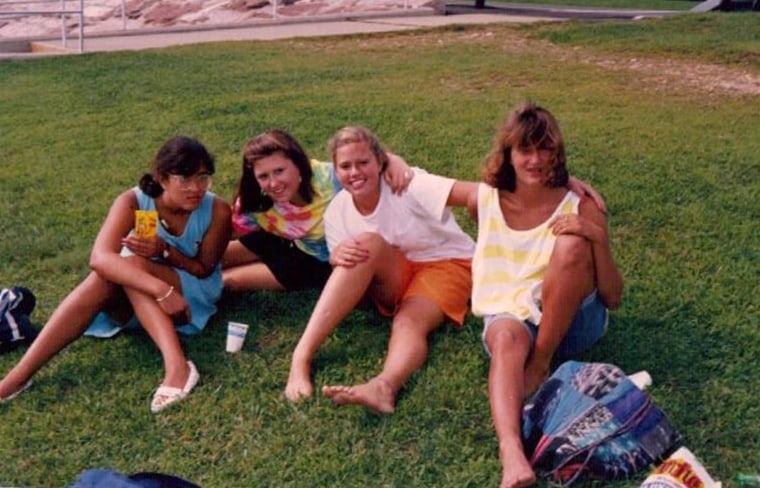

Joan Zelaya used to live in West New York, New Jersey, a densely populated urban metropolis that feels more like Bogota and Havana and boasts a 95 percent Latin American population. When she moved to Athens, Ohio her culture shock was intense.

“I went from listening to merengue, salsa, and other Latin music blasting from cars, and stores, to crickets,” she said. But the 38-year old South Bronx born educator welcomed the change.

“The slower pace and quality of life taught me that there were different ways to live besides the loud busyness of an urban center that sometimes threatens to split your head open,” said Zelaya, who is part Dominican and Honduran.

Living in a place with few Latino neighbors and colleagues taught Zelaya to build a community with the small number of people of color she did find, she said. Yet even with a strong sense of comunidad that Zelaya was able to build, the feeling of otherness never went away.

“You can’t escape that otherness when you are the only Latina or woman of color in the office or in the supermarket,” she said. Zelaya recently quit her job as Co Director of Tutoring Services at Ohio University to move to Dallas. She confessed that part of the allure of Dallas was that it was more Latinocentric, even if she moved there without a job.

“It wasn’t that I experienced overt racism in Athens,” explained Zelaya, a community college teacher, but more subtle "micro aggressive moments."

Some examples, said Zelaya, was when she would be told, 'oh you are so articulate, you speak English so well,' she said. “What they are implying is that only white people are articulate," said Zelaya.

Something that happened a lot in Athens, Ohio was the fascination with Zelaya’s ethnic hair.

“A lot of people asked me about my curly hair and even asked to touch it,” she said. “I’ve had an evolution where ten years ago that would have been fighting moments,” she explained. “I never thought it was my responsibility to teach white people and others about Latino heritage but now I use those incidents as teachable moments--moments to connect."

Saying that she came to see some of these comments came out of ignorance or curiosity, “I realized too that some white people are genuinely interested in my hair,” she said, laughing. “And why not—it’s big and gorgeous. Heck, I’m interested in my hair,” Zelaya added.

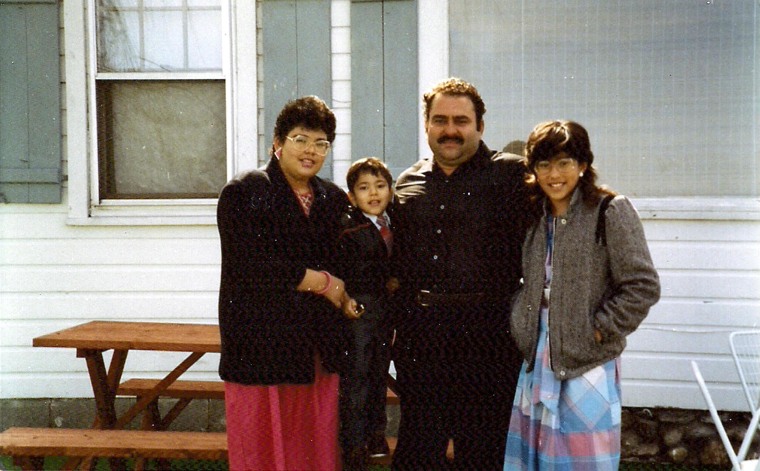

Migdalia Diaz, 38, was born in Puerto Rico, but moved with her family to the culturally homogenous coastal town of Old Saybrook, Connecticut when she was four years old. She now lives in "lily-white" Arlington, Massachusetts, and said she understands what it’s like to be the only Latina in her school and town. But a lifetime of encounters toughened her up, she said.

“Oh I've got stories--when I was a cheerleader in high school some of the girls would ask if all Puerto Rican girls were as flexible as I am,” she said, laughing at some of the comments.

“You wouldn’t believe the ignorance. Once I was walking to get ice cream with my little brother who is seven years younger than me and someone shouted from a car window, “you shouldn’t have had kids so young! If I had been a white teen, instead of assuming he was my son, those same ignorant folks would have assumed that he was my little brother,” said Diaz.

Rather than being defeated, Diaz said she developed cultural dexterity, a skill she employs working as a project manager for an international construction company.

“Living in an all white town taught me how resilient I am,” she said, "and it gave me the perspective of seeing the beauty in all people. There was a point where my friends went beyond the color of my skin and saw me as one of them,” said Diaz.

There was another benefit to cultural isolation--it made Diaz a better cook.

“My mom created little Puerto Rico in our home—she constantly played salsa music, and taught us how to cook boricua (another name for Puerto Rico) dishes from scratch,” Diaz said. “She also showed us our cultural beauty.”

Diaz might have grown up in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, but she is not only bilingual and a good salsa dancer but can cook alcapurrias, arroz con gandules, pernil and pastelillos among other traditional Puerto Rican dishes all made from scratch. She recently discovered a small Latin market forty minutes away and was elated; the closest one was an hour away.

“It’s not a bodega in [New York's] El Barrio, but it will do,” she smiled.