AUSTIN, Texas -- Amid newly-launched campaigns to turn out Latino voters in 2016, a group of scholars and longtime activists are recalling the fights they’ve waged to secure voting rights and political influence for the community and protect them for the future.

The struggle to engage Latinos politically has gone on for decades, boosted by the movement to secure voting rights for black Americans.

But it also took its own route and many of the people who were behind the struggle for voting rights for America’s Mexican-American, Puerto Rican and other Latino populations have been paid little notice.

On Thursday and Friday, some of their stories will get due attention in a conference at the University of Texas titled “Latinos, the Voting Rights Act and Political Engagement.” The conference will lay out the struggle to expand the 1965 Voting Rights Act to Latinos, how it opened the gates for Latinos to run for elected offices at various levels of government, spurred efforts to mobilize Latino voters and forced Latinos subjected to discrimination at the polls to speak out about their experiences.

“My hope is if we understand what it took to secure those votes, then people won’t take it for granted,” said Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez, a University of Texas associate professor of journalism who organized the conference.

Although the Latino electorate is growing, that is largely because of their increasing population and the numbers turning 18 every year. Even though a record 11.2 million Latinos turned out to vote in 2012, another 12.1 million who were eligible to vote, stayed home.

Rivas-Rodriguez has spent years gathering, with the help of her students, the oral histories of Latino veterans and how their service helped spark Latino demands for equality and civil rights. She recently embarked on an effort to collect similar oral histories of Latinos who were supposed to have benefited from those fights for equality, but were subjected to voting rights discrimination.

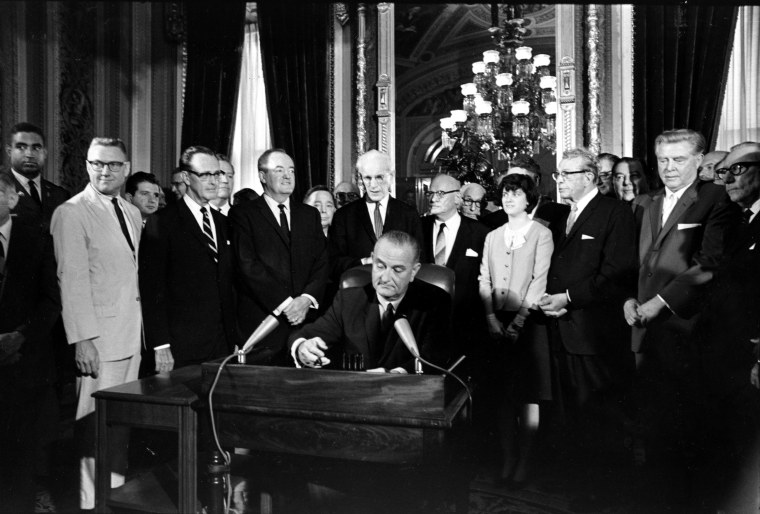

Although the Voting Rights Act was signed in 1965, many experts agree that it was the expansion of the act's voting rights protections in 1975 to "language minorities" that had a greater impact on Latinos.

“As I started doing interviews … I could not find a book about Latinos and the 1975 Voting Rights Act,” Rivas-Rodriguez told NBC News Latino in an interview preceding the conference.

“We’ve uncovered this amazing experience that hasn’t been well documented,” said Rivas-Rodriguez, who teaches a class on oral history journalism at the University of Texas at Austin.

When attorneys were working to show Congress the need to expand the Voting Rights Act, they had to find actual examples and collect people’s stories as evidence.

A professor at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio gathered that evidence and hired an assistant to help him. That person was Rosie Castro, the mother of Housing Secretary Julián Castro and U.S. Rep. Joaquín Castro. She was scheduled to speak Friday afternoon at a panel titled “Mobilizing the Latino Vote.”

The conference comes as Latinos and other minority groups have been imploring Congress to restore protections against discrimination in the Voting Rights Act that were struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013.

Bipartisan legislation crafted to restore and modernize the protections has been stalled in Congress.

With more than 28 million Latinos eligible to vote in November 2016, Latino groups are pressing Congress once again to protect the voting rights of Latinos and others.

“With Election Day less than a year away, it is unconscionable that we still do not have a legislative fix in place that will prevent our nation from holding its first presidential election in more than 50 years without crucial protections in federal law to combat the racial discrimination in voting, which continues to plague our democracy,” Arturo Vargas, executive director of the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials said in a statement.

In addition, over about the past five years, states with Republican-controlled legislatures have enacted or attempted to enact restrictive voting rights laws that ranged from requiring voter ID to reducing the number of early voting days.

Some have said those laws are unraveling the work of earlier decades that lead to greater access to the polls by Latinos and legal victories that have made it possible for more Latinos to hold elected office. The restrictions have come in an election in which the rhetoric and proposal by some candidates has drawn backlash from some in the Latino community.

"The only way we are going to stop the attacks on our community is to raise our voices and participate and to vote. But when that right to vote is restricted, it limits your ability to stand up and fight for yourself, so part of our job is to make sure voting rights are strengthened," Rep. Linda Sanchez, a California Democrat who is chairwoman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, said las month in a news conference on legislation to restore anti-discrimination provisions to the Voting Rights Act.

On the other hand, the Brennan Center for Justice has found that bills that would expand voters’ access to the ballot box are outpacing those that restrict it.

California, which has the highest number of Latinos, recently approved automatic voter registration. Residents are automatically registered to vote when they get a new driver’s license or renew it, unless they opt out.

The Supreme Court is expected to hear a case in which the same group that challenged the Voting Rights Act – leading to the elimination of the Section 5 anti-discrimination protections – is challenging who gets counted when it comes to drawing legislative districts.

The group wants only people eligible to vote, citizens 18 and older, to be counted. If the court rules in favor of that argument, many Latino legislative and congressional districts could be dismantled, diminishing Laitno political power, Ari Berman, journalist and author of "Give Us The Ballot," said in one of the conference's first panel discussions.

Greater Latino political engagement served as a precursor to more Latinos ending up in elected office. While the numbers in elected office aren't representative of the population, there are signs of change.

The 2016 campaign has included two Hispanic presidential candidates, Sens. Ted Cruz, R-Texas and Marco Rubio, R-Fla., and the potential for a Latino vice presidential candidate on the ticket. HUD Secretary Julian Castro is often mention as possibly being Hillary Clinton’s runningmate should she win the nomination.

Latino scholars hope the conference puts a focus on an area of history and civics many may not know and that often is forgotten in discussions of the struggles for fair treatment at the ballot box.

“Latinos have a different experience than African Americans with the 1965 Voting Rights Act,” Rivas-Rodriguez said. “Everything that happened in Selma, absolutely we should know that. All Americans should know that.

“(But) Latinos have another American experience and this is all part of the American story that we should all know,” she said.