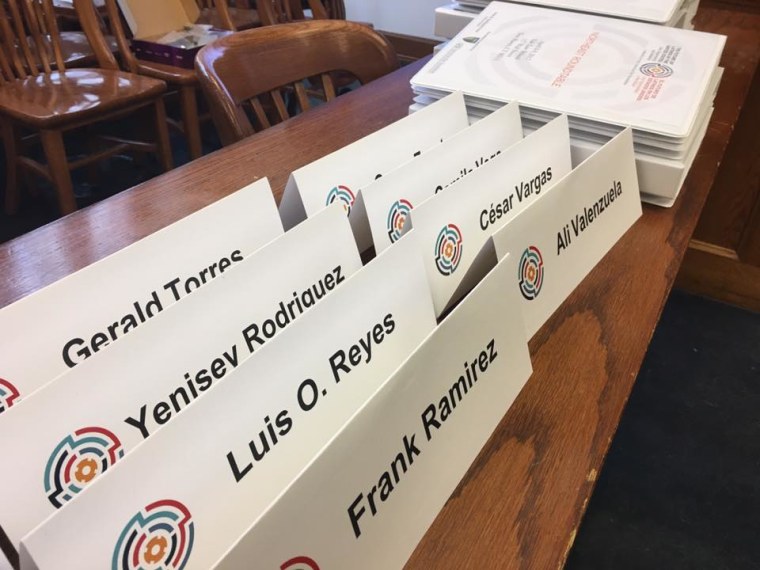

In April I was invited to Yale Law School to attend a conference put together by the American Bar Foundation for their research initiative “The Future of Latinos in the United States: Law, Opportunity, and Moblity.” The gathering featured 50 “key stakeholders”: lawyers, academics, political activists, and members of institutions of the arts and humanities, all brought together to brainstorm about how to devise strategies to advocate for and empower Latinos amid a difficult time in our national and political landscape.

The discussions were tinged with a special urgency from most participants, who were still trying to come to grips with the advent of what we all agreed was a hostile Trump administration. The dialogue was often revealing, if sometimes repetitive, but often resulted in fruitful exchanges that, if not resulting in concrete proposals, identified some crucial areas of concern that Latinos will need to address aggressively.

RELATED: Latino Pulse: Is President Trump Reaching Out to Hispanics?

In the days that followed, I considered the issues that resonated with me the most strongly and followed up with some of the attendees to tease them out even further.

The follow-up conversations seemed to confirm something I’ve believed for many years: As Latinos we have the contradictory task of strengthening and empowering our ideas of what we need as discrete groups, while simultaneously working towards defining our broader national identity. We’ve got to stay on message about the fact that our history runs long and deep in the Americas, while at the same time vociferously defend our most recent immigrants.

This sentiment was captured by Professor Gerald Torres, who teaches law at both Cornell and Yale and is a leading figure in critical race theory, environmental law, and federal Indian law. At one session he told a story about how he was confronted by a nativist anti-immigrant who questioned whether he belonged in this country. He told the man, “One side of my family has been here since 1620, and the other side for 12,000 years.”

There is no doubt that Latinos are unfairly bearing the brunt of the Trump administration’s attacks on illegal immigration—not only are most Latinos in the U.S. born here, but there are an estimated 1.5 million undocumented Asians here, and a considerable number of undocumented from Europe and Africa. As Lorella Praeli, an organizer who worked on the Clinton campaign and has just started as director of immigration policy and campaigns for the ACLU, said that Trump “has declared a war since he launched his candidacy and he is inflicting fear on the whole community.”

But while there is much work to be done to oppose attacks on sanctuary cities, as well as a massive increase in ICE agents, the border wall, and construction of new immigrant detention centers, everyone agreed that the Latino agenda needs to be broader than just one issue.

“Take the environment,” said Torres, “Latinos are among the most ‘green’ voters among any ethnic group,” noting that not only do we have a passion to protect the earth, but we are often victims of environmental racism when city planners put waste management facilities next to our neighborhoods.

“Not only that,” Torres insisted, “but we need to pay more attention to criminal justice issues. When you look at the data, Latinos are executed at a higher rate than most groups in death penalty states. We need to have our long-term vision and strategy that has to include all the issues that speak to our community, from criminal justice to immigration to access to capital, to business formation to education to higher education, to electoral politics, to building a bench so that we can be represented during the local state and national elections."

We’ve got to stay on message about the fact that our history runs long and deep in the Americas, while at the same time vociferously defend our most recent immigrants.

César Vargas, the first undocumented person ever accepted to the New York bar, was born in Puebla, Mexico and raised in Staten Island, New York’s forgotten borough. and the prevalence of Republicans there has prompted him to at least dialogue with them. Vargas’s conversations with Dan Donavan, a US Representative from Staten Island, resulted in an op ed for The Washington Post that stressed their common ground.

“Do my principles align more with Democrats than Republicans?” Vargas said in an interview. “Yes, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to blindly follow a Democratic party," he said, bringing up President Barack Obama's record deportation numbers. "I think it’s important to develop this kind political independence over the next few years decades.”

RELATED: Latinos Usher in a New Era: It’s President Trump

One of the things that stood out for me during the Latino Roundtable was the presentation by Princeton University sociologist Douglas Massey, which was a kind of sketch of the Northeast Latino community. Massey stressed that Latinos are subject to “persistently high levels of residential segregation and high rates of poverty” with race and racial identification driving those twin effects. Since there are relatively higher percentage of immigrants and migrants from the Caribbean in the Northeast, they are more likely to be racialized as non-white.

Yet despite Massey’s unambiguous revelation, some, like Marta Moreno Vega, director of the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute in Harlem, felt it was not enough of a focus for discussion. “The issue of race didn’t even come up,” she lamented. “There was a study that said that Puerto Ricans who are black are closer in all statistics to African Americans in terms of income, housing and education than other Latinos that are lighter-skinned. Even the Mexican population is primarily from Puebla, dark-skinned. To me it was not a Northeast agenda at all.”

Moreno Vega’s point is that it often seems that US Latino identity is constructed in a similar way to the way it is in Latin America, where mixed-race idealism tends to obscure, or even erase blackness and indigenous identity. Torres wanted to embrace both his indigenous identity, and the notion that the mixed-ness of Latinos was a powerful force for change.

“The greatest thing about Latino identity is that anyone in the room could be Latino and there’d be no way to tell unless you asked,” he said. “That’s a strength and not a weakness. It’s distance from blackness that makes you white. Rather than talking about how we can be integrated into American culture, we should look at how we’re transforming the culture. If we could break the racial binary model it wouldn’t just be good for Latinos, it would be great for America."

Another point that Massey made is that, with no clear majority among national groups in the Northeast—Puerto Ricans and Dominicans are almost equal in number, with Mexicans gaining rapidly, the Northeast has the opportunity to become a laboratory for national Latino identity that overcomes the regional divisions: the Mexican West, the Cuban South Florida, and the Puerto Rican-Dominican Northeast.

In many ways this reflects a tradition that has a long history in New York City, where in the late 19th and early 20th centuries Latinos from the Caribbean, Mexico, and South America, and even Spaniards escaping Franco worked together to create a sense of pan-Latino solidarity.

These days that sense seems to have reached up northward to Connecticut. “I’ve always felt, growing up in New Milford, that there were these strong bonds, cultural ties that I think transcend country of origin,” said Praeli, who is of Peruvian heritage. “The language and music and food and diversity of food and music. There was sort of this—éramos Latinos, right? I went to high school with peruanas, ecuatorianas, colombianas, mexicanas, dominicanas y puertorriqueñas. We were all so proud of our own country. There were little things that came up like, oh my food is better. But there’s so much richness in diversity.”

RELATED: Latino Pulse: Scorning the Immigrant With Trump Policies

César Vargas, who worked with the Bernie Sanders campaign last year, has done his share of organizing in the Southwest and Midwest, but in the end is a New Yorker, proud of the sprawling and growing Mexican community.

“Here in Staten Island, Port Richmond where it was predominantly African American and Puerto Rican, now we see a whole commercial block of just Mexican restaurants,” said Vargas. It’s been something that’s been really incredible to see, how the Mexican population is creating those alliances with other Latinos, and I see a very positive trajectory in the years to come.”

The future of Latinos, then, lies in tying together a vast array of issues, and learning to make intersectional connections not only among our own communities, but with other constituencies who are also feeling the heat from the new administration. We need to continue the fight to protect voting rights, to even push for non-citizen voting, to create a nationwide initiative to engage in media production, and limit the worst of the damage already inflicted by anti-immigrant and anti-Latino hatemongering.

Praeli feels we need to continue to identify sites for organizing and consciousness-raising that parallel African American barbershops and church networks. “We need more women of color and Latinas running for office,” she insisted. “And we should address foreign policy—it is very important for us and it isn’t true that it’s only the case if you live in Miami or South Florida."

What seems to be required is an extended process of translation, where all the ideas we are generating in gatherings like these, and in our institutions, bodegas, and streetcorners, are turned into something that resembles a viable Latino future. Hard work, perhaps, but something beyond just working out our identity.

“Everybody dances salsa,” said Moreno Vega. “But how do we translate that, for want of a better term, into power?”