HAVANA, Cuba — I heard he had made it to America.

"Finally," his friends said.

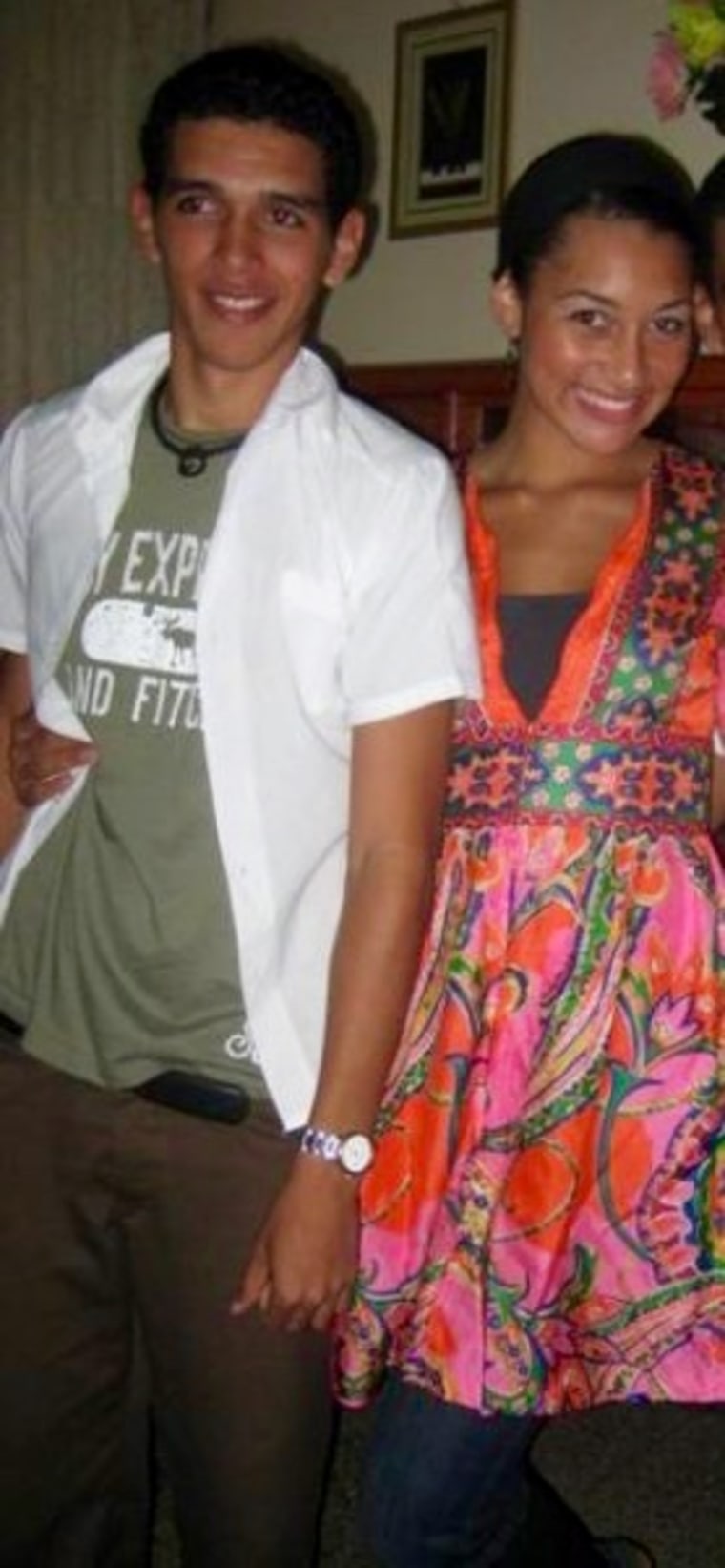

My best friend Javier had always talked about the United States: What it would be like to have Internet ("Is it everywhere, Morgan?"), to travel to different cities ("¿Viajas sin visa?"), and to feel the hustle and bustle of Americans and their non-stop work. ("¿Allá la gente vive para trabajar, no al revés?").

I was happy to hear he'd made it.

It had been nine years since I'd last seen Javier; a wiry boy of 17 who couldn't put on weight no matter how much he ate, despite the fact that his father made the best moros (beans) and tostones (plantains) in town. In fact, that's how I met Javier. His father Tato cooked in the home where I stayed when I was 19, studying at the University of Havana.

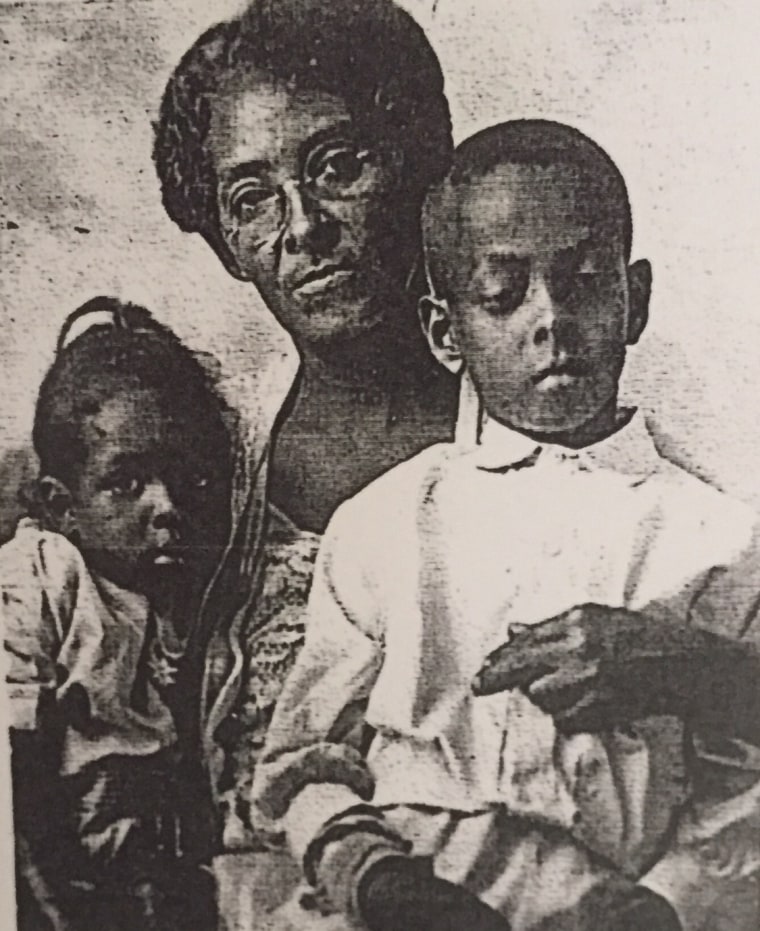

I chose Havana to study for my fall semester when I was a Junior in college because I desperately wanted to see the land that my own family had come from. My great-grandparents met in Cuba; my grandfather was working on the railroads and she was a Jamaican immigrant looking for a better life. They met, fell in love, and soon started a family in Camaguey. For them, it was the land of opportunity: health care, a good education, stable jobs.

For me, almost a century later, not so much. My first week I could hardly eat; I lost weight and struggled to keep anything down. Tato made unas sopitas (soup) and un arroz con huevo (rice with fried egg on top) and slowly helped me rebuild my appetite.

Javier worked with his Dad, laying out small plates and pouring juice in the small dining room adjacent to his father's kitchen. As I ate, his son and I talked.

"Do you miss your family?" he'd ask. "What's it like to be so far away from them?"

Soon, the conversations turned to politics. Who was responsible for el bloqueo, as Cubans called the U.S. trade embargo. Was it the U.S. — depicted in children's cartoons on Cuban state TV as the villainous "Uncle Sam"? Or was it Fidel Castro, then the country's president, for his record on human rights?

Javier and I argued. We fought and took different sides - at different times - on the same topic. Finally, we agreed that the never-ending cycle of political delitos (offenses) between the two countries made each side responsible for the other. And neither of us, we decided, was wrong.

Javier, Tato and I grew close over those months and during those discussions. Our companionship was rare, our friendship special. We'd go to Javier's house after school, sit with his mom and have dinner. We went to the beach on rare occasions, once getting detained for four hours in a police station because the police didn't like un cubano traveling so closely with una extranjera (foreigner).

It was only then that I understood all the other slights Javier had probably felt over the past months while I meandered along, blissfully unaware: The way he waited outside while I went into a hotel to use the internet once a week since Cubans weren’t often welcomed in tourist-heavy areas. Javier, others explained, was supposed to be protected from my “capitalist ideas,” and to me, they said, it would protect me from any native Cuban possibly pestering me for money.

Javier never let those barriers — however real they might have been for him in his own country — affect our friendship, or my feeling that I was a part of his family.

The day before my visa expired and I was set to return to the U.S., we spent the entire night walking the streets of Havana. Horns were blasting down the main drag of Paseo and impromptu salsa sessions were breaking out on the corner of Línea, where small crowds gathered to enjoy the warm air amid loud conversations going late into the night.

We walked past my University. Even though the buildings were small and their paint was crumbling, the ideas inside were fresh and the debates were vibrant. We sat in our favorite park on Calle G and then watched the sunrise along El Malecón, the famous boardwalk surrounding Havana.

When dawn came, a green, beat-up 1950s Chevrolet pulled up, ready to carry me and my bags back home. Standing there, looking down at my belongings, my heart broke. Tato and Javier had shown me the warmth of the Cuban spirit, what it meant for people to make roughly 17 dollars a day and still be willing to give you the shirt off their back.

At that moment, in front of me stood my best friend, yet I knew that given the frayed relationship between our two countries, I would possibly never see him again.

"Muchacha,” Javier said as we hugged goodbye, “Soy tu amigo para siempre. I won't forget you."

I spent the next days thinking of Cuba, thinking of all the memories I wanted to savor while adjusting to life back home. I called Javier and Tato every week. Later, every month. Soon after, not at all.

Years passed, we lost touch, and I heard Javier moved to the States. I couldn't find him.

When news came of Fidel Castro's death, I had just landed in New York from Paris. I came home and started to unpack my bags when I saw the notification on my phone: "At age 90, Fidel Castro, Leader of the Cuban Revolution, Has Died."

I emailed my boss immediately with just three words: "Send me. Please."

Three hours later I was on a plane to Cuba. I had waited nine years for this moment, reading every article written about the country, following every government appointment and studying the biographies of each of the revolution's major leaders.

When I got off the plane, I saw the Cuba that I loved but not the Cuba that I knew. All of my friends were gone; one had fled to the border through Ecuador, others had gone to Europe to study and Javier and his family were in the wind.

I spent two days covering the initial ceremonies for Fidel Castro, almost effortlessly falling back into my routine - going to the park on Calle G to pay a black-market hustler for one hour of internet usage, walking 20 flights of stairs in the dark to get to my room because of (another) rolling power outage and showering on my knees with cold water for four days in a row.

But while I remembered the rhythm of life in Cuba, our news coverage schedule was grueling; I went directly from my hotel to our live shots without much time in between.

As we headed to do our final live-shot from Havana for MSNBC, I saw a street that looked familiar.

"Are we on 13th Street?" I asked the driver. Yes, he answered. "Can we turn here?" He reminded me I had 45 minutes to be on air. "Just a second," I pleaded, "It'll only take five minutes."

I recognized my old house right away. Since no one I knew still worked there, almost a decade later, I just wanted to snap a photo and leave.

As soon as I climbed out of the taxi, a man lingering outside by the gate turned, opened his mouth, and ran to hug me as recognition flooded his face.

"Morgan?"

"Albertico?!"

Albertico used to work around the house. He told me to come back to the kitchen, Tato would be thrilled to see me.

Tato? I hadn't heard his name spoken in years. "¿Todavía está aquí?" (Is he still here?) Yes, he explained. "Follow me."

I walked down the hallways, passing my room on the left. I walked down the short set of tiled steps connecting to the kitchen outside, covered by a small plastic roof.

"Tatoooooooo!" I yelled. He turned. A smile spread across his face. "Mi niña," he said, hugging me for what felt like an eternity I never wanted to end.

"Have you seen Javier?" he said. No, I explained, I didn’t know which state he was in or how to find him. "No, mima, he's here. At the house. A few blocks away."

I felt a lump in my throat.

Tears fell from my eyes like they had in that same spot so many years ago.

I took their home phone number and address. "The house behind the black gate," Tato explained.

Zooming past 1950s cars, the taxi and I swerved to make my live shot, since my interview with Elián Gonzalez was about to air. It had been years since Elián was a little boy whose bitter custody battle became symbolic of the increasingly frayed relationship between Cuba and the U.S.

As soon as I was done, I called Tato's home. Javier answered on the first ring.

"Oigo."

"Javier."

"It's La Chancletera." (My love of flip flops is world-renowned). "I saw your father today," I said.

"Sí boba, (dummy) he already told me!"

"I thought you were gone? In the U.S.?"

"I never left," he said.

My eyes stung.

"I’m watching the ceremony from La Plaza de la Revolución until 11 p.m. Come by my hotel tomorrow at 10? We'll spend the day together before I leave for Santiago de Cuba."

"See you then."

By 9:45 a.m. I was sitting in the lobby.

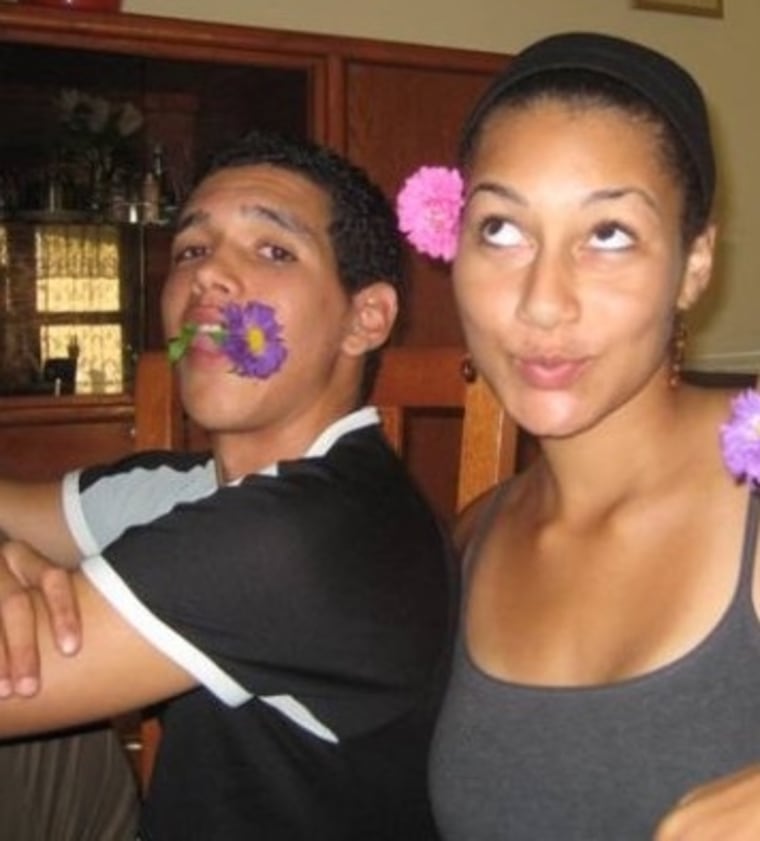

After five minutes, I looked up.

Another pair of eyes across the lobby looked up and locked eyes with mine at the same time.

We had both been there, waiting.

We stood up, as if pulled by strings of the same puppet master. All the makeup I had so diligently applied wound up on his shirt. "Muchacha. No llores," he said.

I couldn’t help it.

"I didn’t know if I'd see you again."

"Me either," he said. "Let's walk."

RELATED: Voices: Trump Win Casts Shadow on U.S., Cuba Relations

We spent the entire day together, as if my taxi so many years ago had never come, my bags had never been packed, and I'd never gotten on that plane.

We walked to my old school, passing through the secret shortcut he had shown me years ago to shave five minutes off of my 30-minute walk. We went to my old boxing gym, Rafael Trejo, where some of the greatest Cuban fighters (and yours truly) trained with only one ring and three beat-up bags. We ran across Calle 23, laughing as my chancletas hit the pavement. We spent hours talking — and arguing.

"Its not our fault we don't have internet everywhere!" he said when I asked if he was upset he still couldn't have things other people our age have.

"Do you think things will change? Now that Fidel's not here?" I asked.

"He's been out of politics for years, Morgan. You're missing the point," Javier said. "As long as we can't have free trade and travel with the U.S., there's nothing we can do domestically to change. The two countries have to work together."

"Do you think that can happen...now?" I asked, making reference to the statements President-elect Donald Trump had made about Fidel Castro moments after his death.

"Based on what he said? No," said Javier.

Unwilling to say out loud what that meant for us, two amigos separated by 90 miles and almost 60 years of bad blood, we walked in silence towards El Malecón.

We climbed on top of the wall, swung our legs around to face the water, letting them dangle as the sun began to set.

RELATED: Analysis: Will Cuba Pivot? It's Up to Raúl

"No sé lo que va a pasar mi amiga - (I don't know what will happen),the relationship between the two countries is so tense right now..."

"It's okay," I interrupted. "They'll find each other again."

"How do you know?" he asked.

"Because I found you."

Morgan Radford is a New York-based correspondent for NBC News.