The late Muhammad Ali’s remarkable life encompasses so many different eras — each one could have inspired its own powerful feature film.

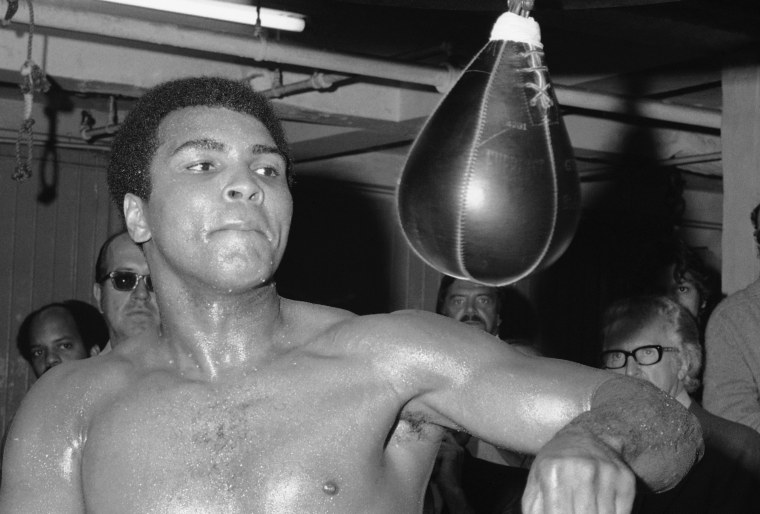

There’s the brash, self-described “pretty” young boxer – then known as Cassius Clay – who burst onto the boxing scene and and proud persona.

Related: Muhammad Ali Dead at 74

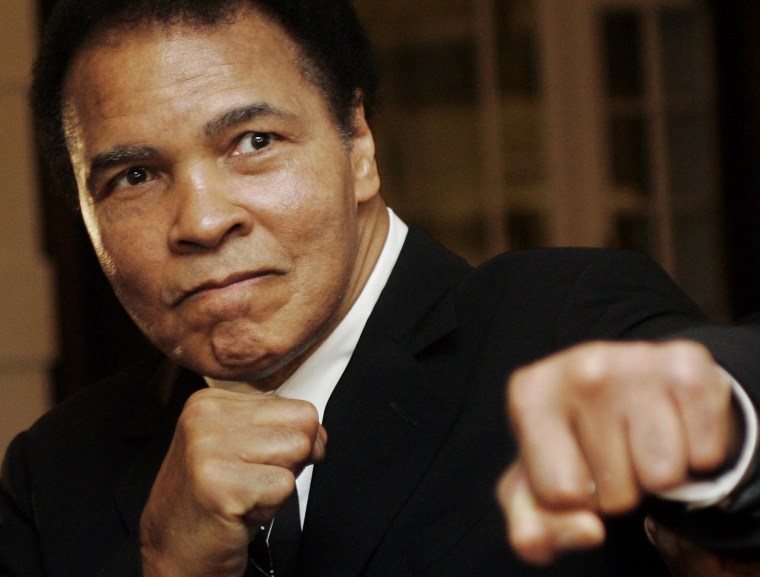

Then there’s the aging Ali, his imposing physique and silver tongue diminished by a public battle with Parkinson’s disease, inspiring the world with his historic lighting of the torch at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

There is only one phrase that encapsulates this man – he originated it, and now we all know it to be true – he was “the greatest.”

Unequivocal heroes are so rare today. In the age of 24-hour news and social media, when a celebrity’s every move and word are scrutinized ad nauseam, it’s possible that some of Ali’s exploits would be received differently in some circles today. But like any man, Ali was a product of his times. In the wake of the deaths of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, he picked up the baton to be a role model of black manhood for a whole new generation of African-Americans.

Few athletes prior to Ali or since have displayed his unique combination of charisma, cleverness and cultural sophistication. Although he was not highly educated, Ali managed to be an articulate voice for a community that was starting to come into its own and assert its individuality.

Related: Remembering 'Rumble in the Jungle,' Muhammad Ali's most famous fight

Before Ali’s arrival, the few African-Americans who were able to achieve crossover success in the sports and entertainment world were expected to be seen and not heard. If they were heard, they were expected to be grateful and demure, a “credit to their race” – the more soft-spoken, the better.

With a burst of braggadocio, Ali destroyed that model of a black star. He boasted, he predicted victories — and then delivered on them, and he made no apologies for who he was and what he was. That made him a villain to many white Americans. But by the same token, he became a true people’s champ, cheered on by young African-Americans who saw him as a counter to the status quo power structure.

His fights are so legendary that they earned colorful nicknames that still stand the test of time — “The Thrilla in Manilla,” “The Rumble in the Jungle.” Some still contend he is the best to ever grace the sport, but his greatest extended outside the world of boxing.

Ali reached iconic status with his refusal to be conscripted into the military during the war in Vietnam. Although history has looked kinder on his decision (“They never called me n—–,” he once infamously said of the Viet Cong), in 1967 it turned him into a pariah and cost him his championship belt.

Today, Ali’s principled stand is hailed as game-changer, not just in sports, but in American culture. The wisdom of his decision was borne out as that war devolved into a quagmire that many Americans now consider to have been a costly folly. Ali the political figure was born.

By this time, Ali was already affiliated with the controversial Nation of Islam, whose black separatist rhetoric would likely still shock many people today just as it did 50 years ago. Still, while Ali did espouse the teachings of the group’s leader Elijah Muhammad, he also rose above them with his good humor and warm-hearted personality.

Eventually, Ali left the group, but he never wavered from his Muslim faith. In later years he became aniconic and moral voice against Islamophobia here in the U.S. (late last year he condemned Donald Trump’s proposed “Muslim ban”) and around the world.

Photos: Float Like a Butterfly: Muhammad Ali's Life in Pictures

In the 1970s he was perhaps the most exciting and influential sports celebrity on the planet, and by then he had completely redefined what a black athlete could look and sound like. He would win and regain the heavyweight championship title twice during that decade, repeatedly proving his detractors (like his friendly foe, sportscaster Howard Cosell) wrong, while giving his fans yet another opportunity to fall for his prodigious gifts.

But Ali was also enduring a brutal physical punishment during his heyday that few could have recognized or appreciated. Because he remained his handsome, ebullient self for so long, many fans barely noticed as his speech became fainter, his gait slower. By the 1980s, when he finally retired after a few fights too many, he was already a shell of his former self. Still, no one could have predicted what the next 30-plus years would bring.

Although his Parkinson’s was never officially linked to his years in the boxing ring, the blows he took couldn’t have helped. And while it would have been easy for Ali to hide from the public eye, so as not to detract from his formidable persona, he chose instead to be as up front as possible about the disease and its effects.

Related: When 'the Greatest' followed his conscience

By doing so Ali became larger than life again. His ability to deliver his classic lines (“float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” “I’m so mean, I make medicine sick”) was gone during the last years of his life, but his very presence spoke volumes.

This man, this father, husband, Olympian, champion, hero — he was bigger than the sport of boxing, and it’s not a coincidence that it has precipitously fallen out of favor with the public since his departure. He was in so many ways the personification of our American ideals — our pursuit of freedom, of our own identities, of the ability to make an impact unfettered by our backgrounds or our faith.

That dream will not die with Ali, but a piece of it will surely always be missing.

This article originally appeared on MSNBC.com.