Two and a half years after the shooting death of Michael Brown catapulted Ferguson, Missouri, into the national spotlight, residents are heading into voter booths to decide whether it’s time for a new leader.

On Tuesday, voters in the town of about 20,000 will choose their next mayor for the first time since the summer of 2014 when Brown, an unarmed teenager, was shot and killed by police officer Darren Wilson. Weeks of unrest followed and exploded again when a grand jury decided not to charge the now-former Ferguson police officer with a crime.

"The reputation Ferguson has nationally is very different than it has in St. Louis," said Mayor James Knowles III, who became the public face of the town in the weeks after Brown’s death, and is seeking a third three-year term.

"I think Ferguson needs to make sure that we continue to have steady leadership moving forward," Knowles told NBC News. "I don’t think anybody can tell you that we haven’t done a tremendous amount of positive change in this community."

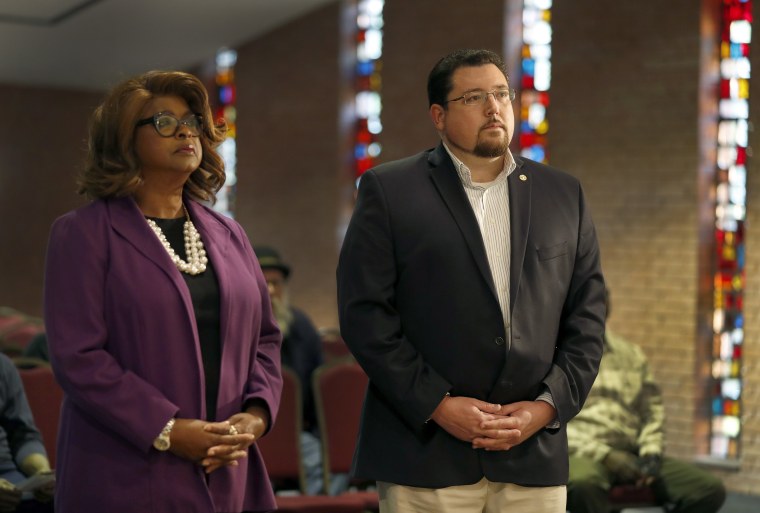

In this city where race has been such a huge and divisive issue, it’s important to point out that Knowles is white and his challenger Councilwoman Ella Jones is black.

Jones is part of a new, diverse group of leaders who have assumed their positions in a city now under a federal court order to reform its police department and courts. Only one city council member remains from the time of the unrest. Ferguson has a new police chief, city manager, and chief judge. Jones is trying to convince the city’s residents that Ferguson also needs a change at the top. She has been aggressively campaigning in the more disadvantaged parts of town, like the area where Michael Brown was killed.

“Their number one concern is that ... this mayor that we have does not care anything about them,” said Jones, who previously worked as a salesperson for Mary Kay Cosmetics.

She has often said that Ferguson is a tale of two cities: “It’s a city of haves and have-nots.”

But Knowles rejects that idea, saying, "We’ve been bringing people together. We’ve been reaching out to people who feel they haven’t had their voices heard."

The police department and how cops operate in minority neighborhoods remains an intense issue. The department, under a court decree, must make sweeping changes to end what the Obama administration’s Department of Justice found to be a pattern of discriminating against and targeting mostly poor black residents.

One immediate challenge is recruiting more officers: The force is down some 25 percent to about 40 officers.

“Every police department in St. Louis is short,” Knowles said. “And I hear that all across the nation.”

But he also admits that it’s difficult for a smaller force to move toward community-based policing, one of the most essential elements of the court ordered reforms.

“You know, that’s labor intensive,” he conceded.

For his challenger, the situation is more dire.

"People are still hurting," Jones said, specifically referencing the fact that Wilson was not charged in Brown’s death. "And until we get to the root of the problem, that hurt is still going to be there."

To illustrate the deep gulf of mistrust that still exists, Jones and others have pointed to an incident last month when a small crowd confronted police after a video was released that showed Brown the night before his death. Activists said the video proved that police were hiding evidence. Authorities said it was irrelevant.

Something else that might impact votes: the state of local businesses.

When Ferguson descended into unrest after Brown’s death, Natalie DuBose’s bakery was one of the casualties.

Situated just down the street from the local police department, Natalie’s Cakes and More had only been open for a few months when tensions boiled over. DuBose’s shop was one of those vandalized one night during riots, with windows smashed in and equipment damaged. Heartbroken, she started a GoFundMe page with the goal of raising $20,000 for repairs; she ended up getting more than $250,000.

“The tragedy, it turned out to be a triumph,” she said while standing in her now-thriving bakery, which is undergoing renovations and expanding thanks to an investment from Starbucks. The company now features her sweet delights in dozens of its stores around St. Louis, as well as a new one right in Ferguson.

DuBose thinks things are going well in Ferguson: “It’s moving in the right direction.”

The owner of “The Goody Bag,” a candy store on West Florissant Avenue, is optimistic, even though his previous business suffered during the unrest. His family’s health supply store was burned to the ground during one of the worst nights of violence.

"We still gotta have businesses, people got to have interaction, you gotta deal with kids," he explained. Adding, "Just because bad things happen it don’t mean you should just leave the area."

Take a drive around Ferguson, and it’s evident that there has been progress. A brand new $25 million dollar service center facility built by Centeen, a health care company, created 200 jobs. The company, like Starbucks, decided to open in Ferguson in an effort to help the community rebuild.

But it’s also easy to see the deep scars and the businesses that never came back — like the Burger Bar just a few doors down from Drake’s candy shop.

So, the question for voters seems to be whether Ferguson has moved forward enough, fast enough — and whether this city that helped ignite an emotional national conversation about race, policing and protest, has left that difficult past behind.