This June marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Gwendolyn Brooks.

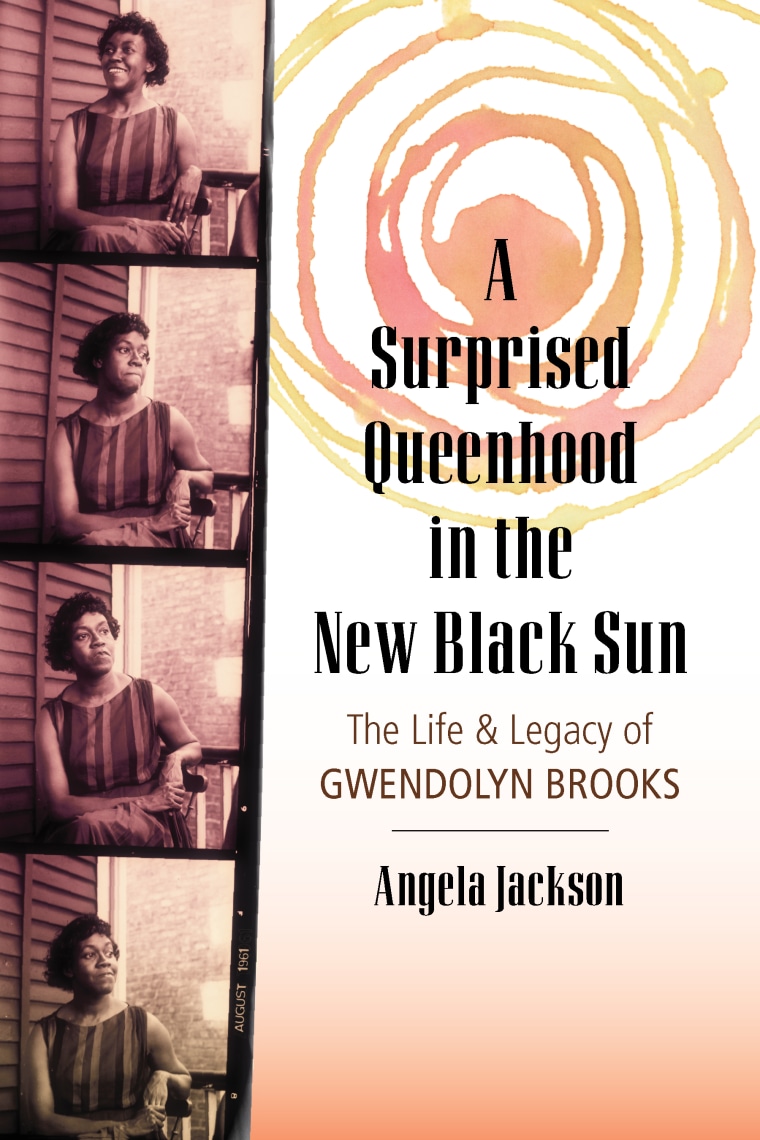

The celebrated poet was the first African American to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. In commemoration, award-winning poet and novelist Angela Jackson and Beacon Press have published A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks.

Jackson explores Brooks' life, getting unprecedented access to Brooks' family, her personal papers, and more. Jackson also examines forty-three of Brooks' poems to give better context and explain the deeper meaning behind the works.

Below is an excerpt from A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks.

In her 1972 autobiography, Report from Part One, Gwendolyn Brooks wrote:

I—who have “gone the gamut” from an almost angry rejectionof my dark skin by some of my brainwashed brothers and sistersto a surprised queenhood in the new black sun—am qualified toenter at least the kindergarten of new consciousness now. Newconsciousness and trudge—toward—progress.I have hopes for myself.

Gwendolyn was further along toward her queenhood, and further than in a kindergarten of black consciousness, further than she herself knew. After all, she was a favorite daughter of the Negro community and had achieved the status of an icon when in 1950 she became the first black person to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

Throughout the 1950s, she did not travel much and gave a limited number of readings, but by the 1960s, as her daughter, Nora, grew older, Gwendolyn became a regular presenter of her works in Chicago public schools, from Copernicus to Tanner, down the street from her house. She had a special way with children, who loved her expressive style and her ease with them. She was Somebody, and they knew it.

In 1962, she and Langston Hughes were the only Negro poets to read at the National Poetry Festival, sponsored by the Library of Congress. In 1965, the Metropolitan Community Church honored her at a testimonial at the Pick-Congress Hotel, in downtown Chicago.

She was royalty, of a kind.

It was the young black people who had ignited the fires that smoldered in her, the young black poets who had put the light in her eyes. A new world beckoned.

Even before the Fisk Writers Conference of April 1967, in February 1966, she had given a reading in Rochester, Michigan, and met another poet who would be important on her path to the new Black Consciousness. Dudley Randall struck her as a gentle man, not at all as she had anticipated from his tough reviews in Negro Digest. “Oh, you’re Dudley Randall. I thought you were terrible, but you’re all right,” he remembered her saying. They had dinner at his house, with his wife, and poets Oliver LaGrone, Joyce Whitsit, and Harold Lawrence. Randall was a longtime admirer of Gwendolyn’s poetry and asked her to contribute to his publishing house.

Related: 14 People Who Broke Barriers to Make Black History

Broadside Press was born when Randall published his own civil rights poem, “Ballad of Birmingham.” He asked Gwendolyn if he might do broadsides of her poems “We Real Cool” and “Martin Luther King Jr.” Soon, Randall and Margaret Burroughs were editing an anthology dedicated to Malcolm X. Gwendolyn sent her legendary poem “Malcolm X” for what would become Malcolm: Poems on the Life and Death of Malcolm, published in May 1967.

In 1968, Don Lee was published through Broadside Press. He had been recommended by Margaret Burroughs after self-publishing Think Black. Broadside Press published Black Pride, then the blockbuster and artistically ground-breaking Don’t Cry, Scream. Lee was satisfied with his publisher and wanted to contribute even more to the development of the black community. He knew that Gwendolyn had reached the point in her political sentiments that she was ready to move from Harper & Row. He influenced her to publish her new work at Broadside Press.

Gwendolyn listened and agreed. But make no mistake about it— she put her work where she professed that it should be. She expressed black unity and fidelity to black economic prosperity and the liberation of black psyches. She believed that she had to build up a black publishing house. It was, she believed, her duty. Lee stressed to her the importance of institution building, of building black schools, publishing houses, and organizations that would live beyond the lifespans of their founders. This business of institution building was central to the thinking of the Black Arts Movement in Chicago which, as it turns out, would prove to be the intellectual center of the movement. Gwendolyn was in the thick of things.

In 1968 and 1969, she and Lee often gave readings together across the country. In the beginning, she would read from her work and then introduce the younger poet to the audience. Lee was a dynamic reader and did not disappoint Gwendolyn’s faith in him. She was acting as a poetic mentor. After a time, Lee became dissatisfied with the order of their readings. He found her reading before him disrespectful of her as the elder, more esteemed poet. He insisted on reading first and presenting her. She was, after all, Gwendolyn Brooks, a kind of mother to a group of younger black poets, particularly Lee and Walter Bradford.

Ann McNeil, now Dr. Ann Smith, met Gwendolyn Brooks at Northeastern Illinois State College in the fall of 1966. They had “cubbies,” cubicles, close to each other. Gwendolyn was teaching in the English Department; she had a title of some distinction—Distinguished Lecturer—but no official trappings, not even an office. Smith was familiar with Gwendolyn, of course, from her writings. As a professor and an actor in the Speech and Theater Department, Smith was well versed in black literature, and Gwendolyn was a key figure. In person, Smith noticed that Gwendolyn was “quiet, unassuming, intentionally shy. She didn’t reach out to be the center of attention, even when she was. She did not seek the limelight.”

As their friendship developed, Smith found Gwendolyn had a sense of humor and that “her conversation was like her poetry. She didn’t waste words. She was self-deprecating and very kind.” Smith remembers Gwendolyn’s deceptive simplicity, even her “simplicity in attire. … People would say that she was stand-offish, but in fact, she was shy.” In truth, Gwendolyn was shy, but she could be stand-offish, too.

Related: From W.E.B. Du Bois to Octavia Butler: Your Spring Reading List

When Smith first met Gwendolyn, neither was involved in any black groups. But in 1967, Smith met Hoyt W. Fuller and became involved with OBAC. That same year, Gwendolyn took a different route to become involved with some of the same people. By the spring of 1968, Smith knew Gwendolyn better through her involvement with a special celebration of her work at Northeastern Illinois. At that program, Smith performed Gwendolyn’s poem “the mother,” and Jeff Donaldson, OBAC visual artist and actor, presented her “of DeWitt Williams on his way to Lincoln Cemetery.”

Gwendolyn would list Dr. Smith in her inner circle. This relationship expanded the shy poet’s circle within the Black Arts community. But she had always been a part of Chicago, even if she had always considered herself somewhat of a loner. In May 1965 when it was reported that Chicago had paid homage to Gwendolyn, it was also reported that she had paid homage to Chicago. “Asking me why I like Chicago is like asking me why I like my blood.” She had never been called the poet of Chicago but said it would be a great honor if she was.

By January of 1968, homage to Gwendolyn would be institutionalized statewide when she succeeded Carl Sandburg as the poet laureate of Illinois. Of this appointment, Gwendolyn said, “Being the state’s poet laureate is an honor for which I will receive no pay. … And that’s only fair because right now, I don’t plan to write any poems.”3 But she managed to write beautiful poems as laureate, most notably, “Aurora,” which she wrote in January 1973 for the inauguration of Governor Dan Walker.

We who are weak and wonderful

wicked, bewildered, wistful and wild

are saying direct good morning

through the fever

It is the giant-hour,

Nothing less than gianthood will do;

nothing less than mover, prover,

shover, cover, lever, diver

for giant tacklings, overturning new

organic staring,

that will involve that will involve us

all.

We say direct good-morning

through the fever,

across the brooding obliques, the

somersaults, ashes

across

the importances stylishly killed:

across

the edited bias,

the waffling of woman,

the structured rejection of blackness.

Ready for ways,

windows,

remodeling spirals; closing the hot

clichés

Unwinding the witchcraft.

Opening to sun.

This is the Gwendolyn Brooks of mysterious language as in Annie Allen. She is poet laureate and a bit studied, beautifully.

Excerpted from "A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks" by Angela Jackson (Beacon Press). Reprinted with Permission from Beacon Press.