The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which barred states from considering a voter's sex in determining eligibility, is commonly credited with expanding the right to vote to women, but the amendment didn't actually guarantee all women the right to vote. Although the amendment, which was ratified 100 years ago Tuesday, eased the obstacles some women faced at the ballot box, Black women still faced legal barriers.

"For Black women, our right to vote is only secured with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965," said Valethia Watkins, an associate professor of Africana studies at Howard University. "Black women have only had the legal protected vote for half the time of some other women."

The centennial, coming the same year as the 55th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act and the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment — the amendment that granted Black men the right to vote — marks just one of several major anniversaries in America's complex voting rights history. But to Watkins and other Black women, the high-profile nature of this particular anniversary also serves as a reminder of the ways the suffrage movement fell short for women of color, many of whom found themselves facing discrimination from the very women alongside whom they were hoping to secure rights.

The anniversary also comes the same year in which Black women are running for office in record numbers, Black organizers continue to protest and demand racial justice across the country and Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., is making a historic run for vice president. The fight of Black suffragists stands as a reminder of how Black women's fight for the ballot has been and continues to be about a more fundamental issue: access to political power.

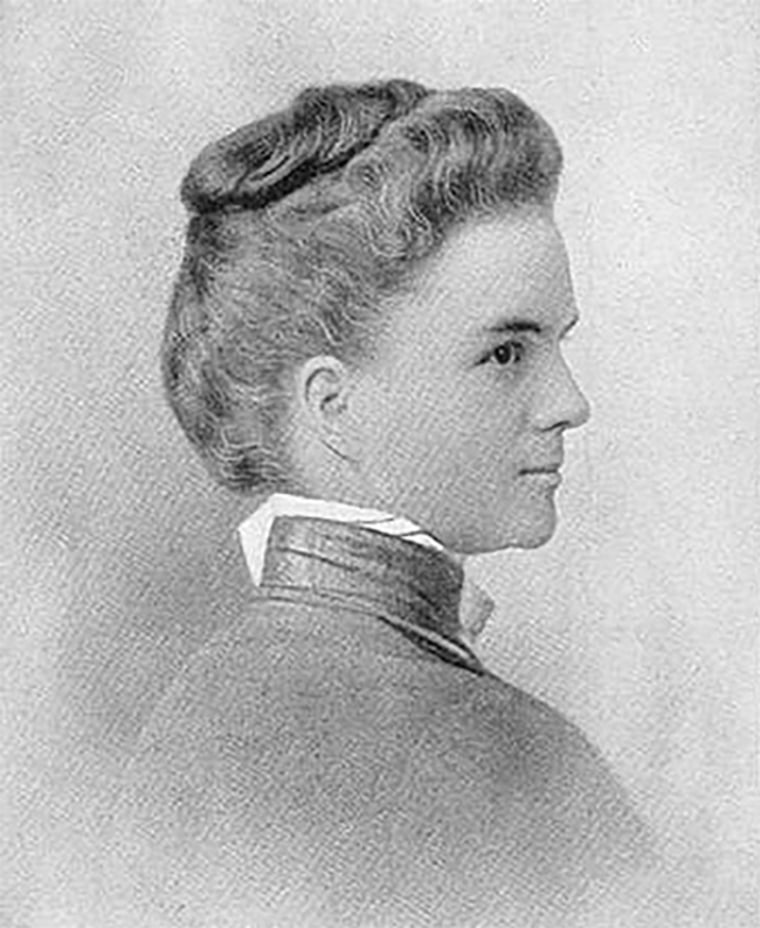

Black women have only recently begun to receive credit and mainstream attention for their outsize political and voting power, and their work within the suffrage movement and the broader fight for Black voting rights is a part of history that has often gone unrecognized. While history recalls contributions of women suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the efforts of Black women like Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the pro-suffrage National Association of Colored Women, or writer and suffragist Adella Hunt Logan of the Black Tuskegee Women's Club have not received as much attention.

The work of other figures, like journalist and anti-lynching advocate Ida B. Wells-Barnett and abolitionist Harriet Tubman, is earning more attention for helping secure the vote for Black women. That work was often done separately from more mainstream white organizations unwilling to consider the unique needs of Black women and their communities.

Watkins said that comparing Black and white suffragists, "the why we fight and how we fight are not the same. For white suffragists, they want to fight for a single issue, and that is the vote. Ultimately, they were fighting for themselves alone."

But for Black women, the fight for suffrage was a multifaceted effort closely linked to other fights for equality within Black communities, including opposition to sexual violence, Jim Crow laws and lynching. As Logan, the Black suffragist and writer, wrote in the 1912 issue of the NAACP's magazine The Crisis, "Not only is the colored woman awake to reforms that may be hastened by good legislation and wise administration, but where she has the ballot she is reported as using it for the uplift of society and for the advancement of the State."

That message was lost on organizations like the predominantly white National American Woman Suffrage Association. When the group organized a 1913 national women's suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., organizer Alice Paul argued that "the participation of negros would have a most disastrous effect" by angering white Southerners doubly leery of women's suffrage and an enfranchised Black population.

According to The Washington Post, when Black women, including Wells-Barnett and members of Howard University's founding chapter of Delta Sigma Theta sorority, arrived at the march, they were told that the procession would be segregated. As the procession continued, Wells-Barnett, who had founded the Alpha Suffrage Club earlier that year, broke from the segregated rear to march with the white members of her Illinois delegation.

Black women continued to raise concerns about their unequal access to the franchise in the years after the 19th Amendment was ratified. While women in some states had been able to cast ballots before 1920, the amendment marked the first time that others would be able to participate in elections. And for others still, particularly Black women, the amendment ushered in a new wave of efforts to suppress Black voters, such as poll taxes, literacy tests and other barriers.

The obstacles would spark a decadeslong push for equal access to the ballot in Black communities, with civil rights activists making voting rights key to their fight for racial justice. And much as with the larger suffrage movement, Black women continued to take a leading role pushing for unfettered access to the vote, with women like Amelia Boynton Robinson and Fannie Lou Hamer working alongside figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis to secure voting rights. The efforts would culminate in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, legislation that finally secured the vote for Black people.

"Women were literally the ones sitting at the table creating the vision, the policy and the mobilization plans for us to actually gain access to the ballot," said Glynda Carr, the president and CEO of Higher Heights for America, a group focused on supporting Black women running for office.

With their votes now protected under law, Black voters began to have a larger impact on elections, culminating in the national contests in 2008 and 2012, when the especially high turnout of Black women cemented their status as the most loyal Democratic Party voters. Fast-forward to 2020, and Black women are demanding a return on their investment, calling for party leaders like former Vice President Joe Biden to support policies that improve their communities and for Black women to be treated as viable candidates for political office.

This year has also brought heightened attention to renewed fights over voting rights in the wake of the Supreme Court's 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, which weakened a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that allowed the federal government to oversee the creation of voting laws in states and counties with histories of discrimination. Since then, several states, like Texas, North Carolina and Wisconsin, have enacted laws, including voter ID measures, that voting rights advocates argue disproportionately make voting harder for communities of color, intensifying concerns about voter suppression a half-century after access to the franchise was expanded.

Given Black women's especially high voting rates, advocates fear that they will be particularly affected, and the concerns have only intensified because of the coronavirus pandemic's impact on Black communities, as well as a wave of misinformation about mail-in voting that has been furthered by the Trump administration.

"If we look at who is running voting rights organizations right now, we see Black women," said Adrianne Shropshire, the executive director of BlackPAC, a group focused on engaging with and mobilizing Black voters. "And that is precisely because our most fundamental right as citizens is under threat."

Black advocates say a new group of Black-oriented voting rights and political organizations, many of them led by Black women, stands ready to face these issues and protect voting rights. But as the centennial of suffrage approaches, bringing with it new opportunities to reflect on the ways Black communities fought for and seized civil rights even when other groups overlooked them, advocates say they continue to look to the legacies of the Black women who preceded them.

"Even when Black women did not win all that they should be able to, they continued to fight and continued to struggle in service of this more perfect union that we are all striving for," Shropshire said. "It is important to understand who is making those contributions and working towards the sort of multiracial democracy that we are all striving for."