Unyielding in its exploration of Black Panther pride, confrontations and in-fighting, “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution” is a documentary that uses rare footage to chronicle the explosive movement in a most comprehensive way.

“This is the first time we had Black people standing up to White people and getting in their face,” said Writer-Director Stanley Nelson.

This expansive story of the Panthers as documented from 1966 to 1973, was a task years in the making for Nelson, “with the weight of the African American upon you,” he said.

With the film premiere at Sundance Film Festival this weekend, Nelson becomes the director with most doc feature premieres of any other filmmaker at this renowned event. In a way, Nelson's achievement is what the Panthers stood for – "power to determine the destiny of our black community" – and respect.

Nelson remembered “being in awe” of the Black Panther Party as a 15 year-old who witnessed police brutality and a housing crisis. “I could relate to the movement as a young Black man,” says Nelson. “It was not religious-based, not about sitting at a lunch counter or riding a bus. And they looked so cool.”

The messaging of the Ten-Point Program of the 1966 Black Panther Party Platform, "We Want Education That Teaches Us Our True History And Our Role In The Present-Day Society" and “We Want An Immediate End To Police Brutality And Murder Of Black People," resonated.

After the untimely passing of friend, colleague, and prolific documentary filmmaker St. Clair Bourne in 2007, who had started filming these iconic figures in history, Nelson ended up with charge to finish it. Seven years later, with the aid of Black Panther communications secretary Kathleen Cleaver, among others, Nelson now has an in-depth two-hour event that challenges the anti-white reputation the Panthers legacy may still hold.

“We wanted a rounded view,” says Nelson whose more than 55 interviews--45 made the actual cut of the film—included a number of police officers, former FBI agents, and footage of white supporters attending rallies and fundraising for the Black Panther Defense Fund.

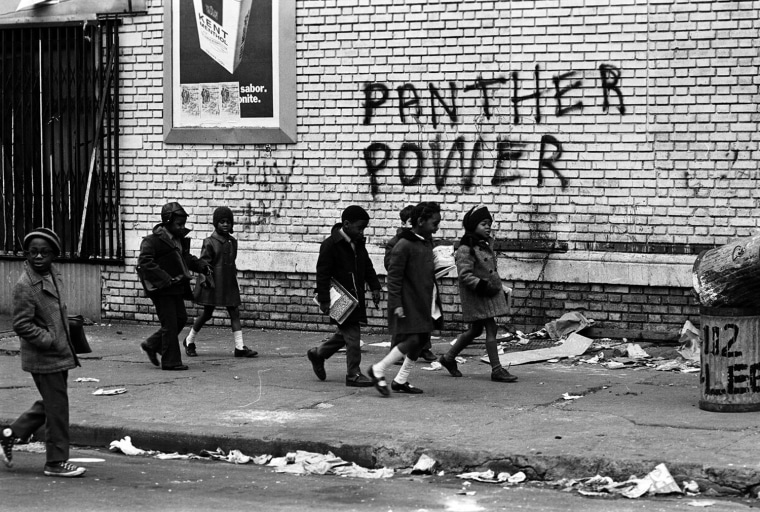

“At that time, the police were seen as an occupying force in Black communities,” Nelson said. “The Panthers said we'll carry our guns and follow the police and make sure police do it in a civil way. At the point when they were patrolling the police, the police didn't want to get into a shootout.”

But the Panthers were no angels. Producer Laurens Grant was responsible for going through mounds of FBI paperwork, cross-checking her findings with volumes of library material in order to locate the documentation to support what seemed to be a mission to destroy the Panthers via jail or death.

“It’s always detective work finding these eye-witness accounts. I met a man who knew Fred Hampton [chair of the Illinois chapter] and survived that shootout, There’s the woman who went into labor while serving the children during the breakfast program,” Grant recalled. “With these stories come responsibility and their memories, traumas, as well as their dreams. And in talking to them now, for some, their Panther party affiliation is a painful question they're still trying to answer.”

The Firelight Media team researched and pursued party members beyond the rank and file. “People who you never heard of who are part of the party doing the day-to-day...your guy sitting there answering the phone, typing the newsletter, on the street selling the paper,” Nelson said.

As the producer, Grant was motivated to track down numerous people and their accounts in order to bring viewers a story beyond what they feel they already know.

“We bring people back into that era, the rich texture of the period. The Party was also very experiential in different parts of the country,” Grant said. “They reflect society and yet wanted make it better than they had it. We put you back in that time so you could see for yourself, how could someone have the guts?”

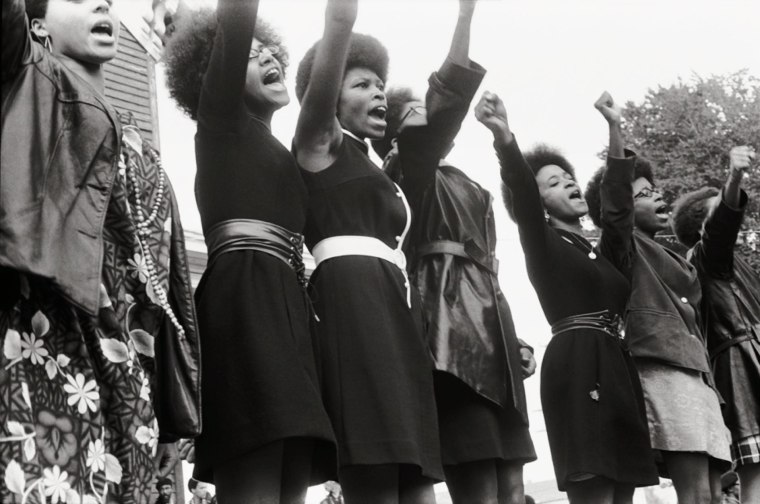

With those guts came that “cool” swagger. The leather jackets, completing the all-black attire, projected an image that played well for the media and captured attention. Unlike the imagery in Nelsons’ previous works “Freedom Riders” and “Freedom Summer” where the style that prevailed was “proper, and very groomed for those non-violent activists fighting the ‘evil’ South.”

Nelson says the Panthers’ look was “not the suits, ties and dresses that donned those who marched with King. The Panthers said we’re going to show you that we're equal or better than dogs attacking, and people screaming at us.”

Part of the award-winning strategy in which the Firelight team never disappoints is rare historical finds. “It's always a treasure hunt,” says Nelson. “And many people are hiding in plain sight.”

One of these magical moments is the verbal fight between founders Eldridge Cleaver and Huey P. Newton. “It was sheer luck,” recalls Nelson, who was approached by an audience member at a “Freedom Riders” screening where Nelson announced his next film was on this topic. “Afterwards this guy comes up and says to me, ‘I have a videotape in my closet of the Panthers in Algeria.’”

He delivered a vintage Portapak tape that the film team transferred. The video caught the moments of the famous phone call where Huey and Eldridge split—from Eldridge’s vantage point where he was on the call on Nigeria.

Huey was involved in the argument while in California on a television program. Grant was able to track down journalist Jim Dunbar who was hosting the television show at the time.

Nelson continues, "We put Huey and Eldridge together, but the audio from the show came from somewhere else - Kathleen [Cleaver] who had a whole big box of tapes at her house. So Jim Dunbar and the show that Laurens found, the tape that the guy gave, and audio tape that Kathleen had all came together to make the one-minute scene.”

According to Grant, digging for such gold is worth it. “The beautiful thing about history is that we learn from the lessons. The larger takeaway is that history affects all of us.”

Some things change and some stay the same. Nelson feels this film as a whole gives a “greater understanding of these young people who are trying to change what will happen in their communities.”

He says, “There hasn't been a good feature-length film about the rise and fall of the Black Panther party. This is a chance to talk about a piece of their lives, one of the most important pieces of their lives."

The Black Panther Party continued to exist past the roughly seven years covered in the film, but “we had to stop somewhere,” says Nelson. “It's apparent when you see the film why we stop there.”

Sundance Film Festival Documentary Features – A Firelight Media Filmography

1) The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords

2) Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind

3) The Murder of Emmett Till

4) A Place of Our Own

5) Wounded Knee

6) Freedom Riders

7) Freedom Summer

8) The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution