In 19 minutes, the sum of Keeth Smart’s life plays out in an inspiring short documentary that speaks to one man’s uncompromising desire to achieve in the face of hardship.

Using a combination of black and white animation, raw family footage and interviews, “Stay Close” illuminates Smart’s ascension from a West Indies community in Brooklyn to the apex of a sport blacks rarely compete in: fencing.

Despite repeated setbacks, Smart made history as the first American to reach No. 1 in the world in saber fencing and later was on the silver-medal winning U.S. team in the 2008 Olympics. That he was black made it all the more compelling.

“Stay Close” premeired last month on the PBS Series “POV Shorts.” The documentary was also featured at the Sundance Festival to enthusiastic reviews. The film moves with the fluidity of a swordsman’s grace, one moment stabbing at the chords of empathy, at another moment sympathy and yet another inspiration.

“We didn’t know why we wanted to do the film until we saw Keeth’s family footage,” Luther Clement, a co-director and a former fencer, said. “It was then we knew that everything went through the parents, and we were guided by that principle.”

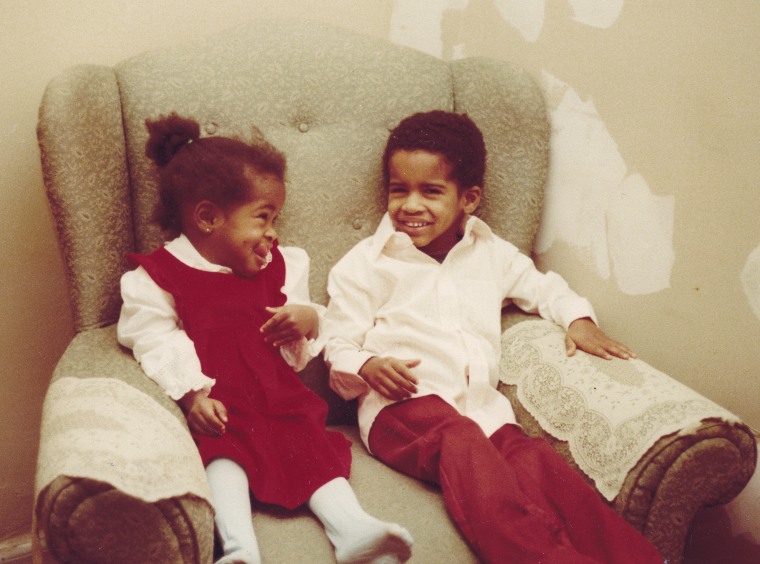

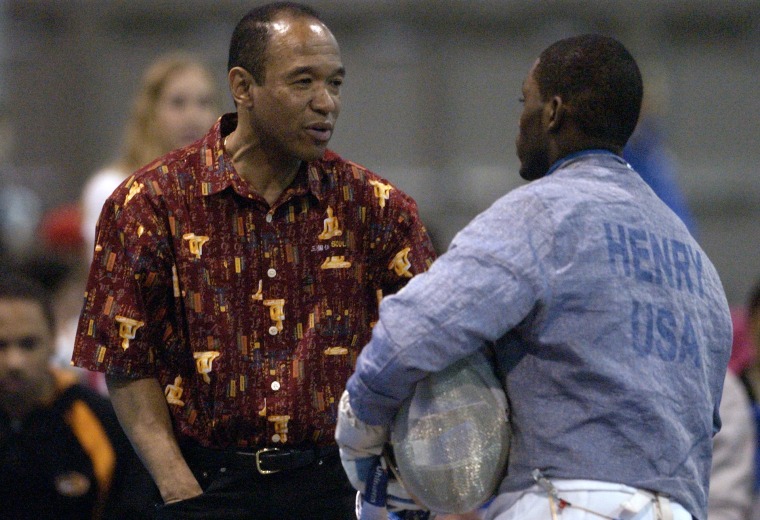

Smart’s mother, Audrey, who emigrated from Jamaica, and his father, Thomas Smart, were determined to send their two children, Keeth and Errin, to college. His father came across an article about the Peter Westbrook Foundation, named after the first African American fencer to win an Olympic medal (bronze in the 1984 Games). The foundation, based in Manhattan, teaches inner-city kids fencing, and Thomas Smart insisted his children take the sport up.

They did, and Westbrook mentored both of them, as he did dozens of young black students in the New York area. Erinn Smart, 9 at the time, was “a natural,” the film points out, and was offered a scholarship from the foundation.

Keeth, then 11, struggled to pick up the sport. But his parents told the foundation that if it gave Errin a scholarship, it had to give one to Keeth.

“We’re not letting our daughter go to the Upper West Side by herself,” Thomas Smart said in the film. “He’s her chaperone. . . and he might as well fence.”

It worked. Both were awarded scholarships. After three years, Keeth showed only modest improvement, but he did not quit. His mother told him: “You’re not like a tiger. Need you to roar like a tiger.”

The roaring did not come until he was the only fencer on the team that did not qualify for the World Championships.

“That’s when I doubled down,” Smart said in the film. “(My opponents) are going to be in a war.”

It was a war he won. Smart earned a fencing scholarship to Columbia University (as did his sister), rose to No. 1 in the world and was the national champion in 2004. All was fantastic. Then, the next year, on a day so hot people were advised to stay inside, his father went for a jog — and collapsed and died.

Before his family could recover, Keeth learned that his mother had cancer.

He and his sister — who would become a four-time national champion and a silver medalist in the 2008 Olympics — alternated weekends visiting their mother in Florida to take her to chemotherapy treatments.

As if that was not enough, Smart got sick after learning he had made the Olympic team. He bled from his eyes and ears, the result of a form of leukemia, and was told his fencing career was over. At the time, his mother was not getting better. “I knew she was dying,” he said. “I wasn’t stupid.”

He fought through his disease, defying specialists. The weekend he was cleared to resume his career, his mother died.

When the Games came, he said he prayed: “Mom, Dad, God, you got to help me through this. “I’ve come too far. Take me home, mom and dad.”

“This film is really therapy for me,” Smart said in an interview with NBC News. “It’s really a family film. It’s been a fun way to recall my parents and what they mean to us and what they did for us.

“If it were not for them, I would never have been introduced to fencing. And I am indebted to the Peter Westbrook and the Foundation because fencing allowed me to skip a couple of grades of life. I have traveled the world, which allowed me to see there was something more, a lot more, outside of Brooklyn. And it allowed me to gain the respect of others.”

That part was not so easy. It is not covered in the film, but Smart said he and his sister and other African American fencers from the Peter Westbrook Foundation endured racism every step of the way, in the United States and especially in Eastern Europe.

“It was really hard,” said Smart, now 41, married with two children in Brooklyn and the executive director of Chelsea Piers Fitness. “When we were 12 and 13, my sister and I spent two weeks at a (fencing) camp in Hungary. We were by ourselves. Our parents could not afford to come. We saw everything under the sun as it relates to racism. They called us every name . . . in their native tongue. And people translated for us. But it taught us to stay together.

“And in the end, we did what we had to do and showed them what they thought of black people was not what their perceptions told them,” he said.

“Which is what the film does as well.”