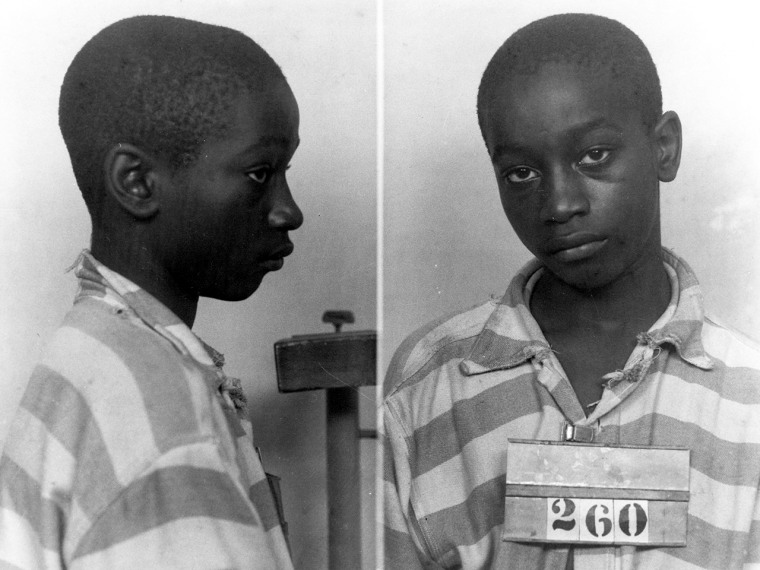

The 95-pound boy wore stripes as the sheriffs walked him to the electric chair, sat him on books to prop him up, and electrocuted him in June 1944.

Nearly 70 years after the execution of 14-year-old George Junius Stinney Jr. for the killing of two white girls, advocates have taken the unprecedented step of asking a South Carolina court to grant a new trial to clear his name.

Stinney is often cited as the youngest person executed in this country in the 20th century. For years, family, advocates and lawyers have said that South Carolina put an innocent boy to death.

“We just want what is right,” said Ray Brown, a filmmaker who is writing a script based on Stinney’s story and recently joined efforts to persuade the state to grant a new trial.

The effort stems from the brutal slaying of Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8, in the spring of 1944. Stinney and his younger sister were the last witnesses known to have seen the girls alive. Police in Alcolu, S.C., arrested Stinney the day the girls were found, and an all-white jury convicted him on the basis of what police described as a confession. Less than three months after the crime, Stinney went to the chair.

"We want them to consider the possibility that he was wrongly convicted and executed for something he did not do," said Brown, who describes the case as a symbol of our history’s deep racial injustices. "You have to correct these kind of things if you ever expect any change."

The request for a new trial is the culmination of a lengthy investigation, started years ago by local historian George Frierson, whose work brought attention to what he calls the barbaric death of a child.

“This was a courthouse lynching,” said Frierson. “I want his name cleared, and I want an apology from the state of South Carolina for putting a child to death.”

Stinney’s execution was legal at the time in South Carolina, where 14 was the age of criminal responsibility. In 2005, the U.S. abolished execution of children under 18.

Brown followed in Frierson’s footsteps, beginning his own investigation, as well as petitioning Gov. Nikki Haley for a pardon. The motion for a new trial marks a shift in strategy to correct what advocates say is a grave wrong.

“After numerous disappointments, blind alleys and dead ends, we believe that we now have sufficient evidence to support a motion to seek judicial review of George Stinney Jr.’s trial,” local attorney Ray E. Chandler said in a statement from Coffey, Chandler and McKenzie. The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

The quest for a new trial faces several legal hurdles. South Carolina law allows a defendant to ask for a retrial if new evidence is uncovered, but it requires the motion be filed within a year of the discovery. Attorneys in Stinney’s case have based their request on affidavits from two of his siblings who provide an alibi for him at the time.

The filing states that the affidavits taken in 2009 constitute new evidence because the family’s fear at the time prevented them from speaking out.

“I wish I could have come forward much sooner,” said Charles Stinney, George’s brother, who is now in his 80s. “George’s conviction and execution were something my family believed could happen to any of us in the family. Therefore, we made the decision for the safety of the family to leave it be.”

It also attributes the delays in requesting a retrial to efforts to obtain a statement from another witness who eventually refused to come forward, citing fear of the Ku Klux Klan.

“You have to explain why you couldn’t have presented the evidence before — that’s a big problem,” said Kenneth W. Gaines, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law. “It’s probably a long shot but I give them credit for trying.”

The effort to win a new trial is a one-shot deal. Such requests are a discretionary matter in the state, Gaines said. Once the decision is made, it cannot be appealed.

A spokesman for the Attorney General’s Office, which would likely be tasked with arguing the state’s case in the event of a retrial, said the office has not received notice of the filing and does not comment on ongoing or potential litigation.

In a 2011 interview with NBC News, Ernest “Chip” Finney, the solicitor for Clarendon County, where the trial took place, said that nearly all evidence and transcripts in the case had either disappeared or been destroyed, meaning it would almost certainly be impossible to prove Stinney’s innocence or guilt by reopening the investigation.

“I would need to have something in order to move the case back to court, something more than just the emotion in the community about it,” Finney said at the time.

The emotion still echoes through Alcolu.

Once the quintessential small company town, Alcolu was split in half. White workers lived on one side of the tracks and black families, including the Stinneys, lived on the other. All lived in cabins owned by the local timber mill, and used coins stamped with an “A” to shop at the company store.

On the day of the murders, two little white girls -- Binnicker and Thames -- crossed those tracks looking for wildflowers. Stinney and his younger sister, Amie, sat on the railroad tracks after school as their cow Lizzie grazed. The girls wheeled their bicycle up to them and asked where they could find maypop flowers, Amie remembered.

"It was strange to see them in our area,” she said in an affidavit filed as part of the case, using her married surname, Ruffner. “Because white people stayed on their side of Alcolu and we knew our place."

News stories from the time said when the girls were reported missing, mill owner B.G. Alderman organized a search party of about 200 people, including black residents. They found the children’s bodies the next day, when, in the early morning light, they followed a trail of small footsteps in damp soil.

The girls had been struck repeatedly in the heads and dumped in a watery ditch. Their bike was smashed and thrown atop their bodies, the flowers they had gathered scattered across the ground.

Stinney and his older brother were arrested that night. His brother was released. George was not. Law enforcement reported that George had immediately confessed to killing the girls with a railroad spike.

In a 2009 affidavit, Ruffner said she was with her brother that day, and he could not have committed the murders.

But his siblings said nothing then, apparently fearing for their lives. The night George was arrested, his father was fired and the Stinneys fled from their company house.

“For my family, Friday March 24, 1944 and the events that followed were our personal 9/11,” said brother Charles Stinney, now in his 80s, said in an affidavit in 2009.

Thirty days after the murders, George Stinney stood trial in Clarendon County. Some 1,500 packed the small courtroom to watch, news reports said.

Prosecutors presented two conflicting statements made by Stinney: one that he had killed the girls in self-defense and the other, that he had chased the girls into the woods and attacked them. No records remain of either confession.

The boy’s court-appointed attorney did not present a defense.

Ten minutes after retiring to deliberate, the jury declared Stinney guilty of murder. Soon after, a judge signed his death sentence.

On June 16, 1944, four months shy of his 15th birthday, the state of South Carolina electrocuted Stinney. Reporters present at his death noted the executioners had difficulty strapping the electrodes to the boy’s small frame. They sat him on a book to prop him up high enough to take his life.

Stinney’s attorney, a tax commissioner with political ambitions but no trial experience, failed to file a notice of appeal, which would have at least delayed the boy’s execution. Several local churches and the NAACP petitioned then-Gov. Olin Johnson to stop the execution. He declined.

The Stinneys were forced to stand by as the state put their son to death.

"My parents were simply helpless to do anything about it,” said Charles Stinney in his affidavit. “They had no money. The law was against them, and they were black in the American South in 1944.”