Gambling on sports is legal in Nevada, where the Las Vegas casino sports books hum with activity under the glow of giant boards that show the point spreads. Just about everywhere else, it’s a black market, right down to the office football pool.

Now New Jersey wants a piece of the action — and it’s waging a court battle that could reshape sports betting across the country.

At stake is the staggering amount of money, up to $500 billion by some estimates, that Americans wager on sports every year. Only about 1 percent of it is legal. The rest is unregulated, leaving billions of dollars in potential tax revenue on the table.

“Every town in this state has people betting on football, baseball, basketball, hockey, on all the major sports, except now it’s being done by criminals,” New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie told reporters in March. “What we’d like to do is to bring it out in the open and have the citizens of the state benefit from it.”

Standing in the way are the four major professional sports leagues and the NCAA, which say legalized gambling threatens the integrity of their games, not to mention their billion-dollar businesses.

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said in a court filing that in a country of widespread state-sanctioned gambling, the simplest bad snaps and dropped passes would create suspicion about game-fixing.

Baseball commissioner Bud Selig said fans might start caring more about their bets than their favorite teams. He also said it’s not just that fans would suspect the fix is in — it would be more likely that people would actually try to fix games.

At issue is a 1992 federal law, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, which banned gambling on sports but grandfathered in four states — Nevada, Delaware, Montana and Oregon.

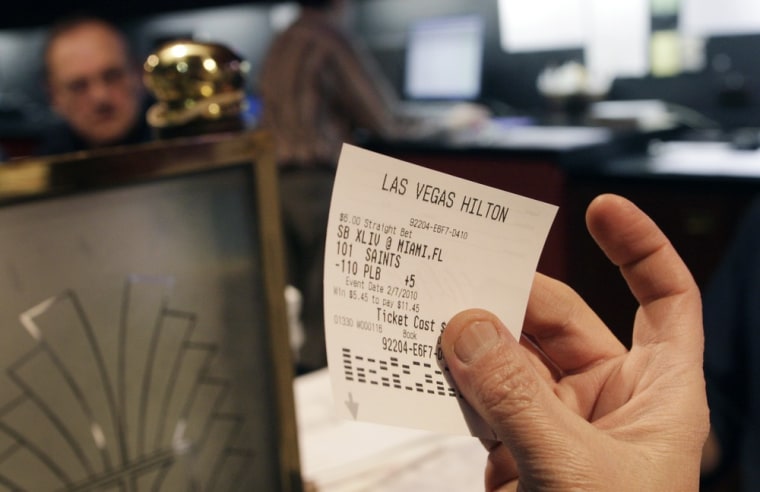

Of the four, only Nevada has unlimited sports gambling today. The Las Vegas casinos take not just bets on the outcomes of games but a dizzying array of side wagers, like point totals and individual player statistics.

Delaware allows parlay bets on NFL games and has been blocked by the courts from expanding. Montana has fantasy football through its state lottery. Oregon ended sports betting in 2007.

No one disputes the appetite for sports gambling across the country. The financial planning website Mint, extrapolating from Nevada data, estimates that more than $8 billion is wagered every year on the Super Bowl alone.

“Americans do not have a problem finding ways to bet on sports,” said Joe Brennan Jr., former director of the Interactive Media Entertainment & Gaming Association, which lobbies for the online gaming industry. “Either the leagues are willfully blind or they’re just incredibly ignorant when it comes to sports betting.”

He noted that unsanctioned sports gambling has thrived even in light of occasional game-fixing scandals, like an NBA referee’s admission in 2007 that he tipped gamblers on which teams to bet on.

In New Jersey, voters approved a sports gambling referendum by almost 2-to-1 in 2011, and the state passed a law months later to allow sports betting in Atlantic City casinos and horse tracks.

The leagues went to court to stop it, and in March a federal judge agreed, saying that the 1992 law limiting sports gambling to four states was a proper exercise of Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce.

New Jersey took its case to the federal appeals court in Philadelphia, arguing that the federal law plays favorites with states. Christie has said that if the state loses there, he will take the matter to the Supreme Court. He says people should be allowed to bet on sports anywhere the voters say it’s OK.

Both sides have heavy legal artillery. The state is represented by Theodore Olson, a former solicitor general under President George W. Bush. The leagues are represented by his successor, Paul Clement.

“They’re our games, after all,” Clement told three judges of the appeals court at an argument in late June. “And we have a legitimate interest in controlling whether these games are going to be sporting events and not gambling events.”

In a twist, the Supreme Court’s decision late last month to upend the Voting Rights Act may help New Jersey’s case.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in that decision that there is a “fundamental principle of equal sovereignty among the states.” Olson rushed a letter to the appeals court, arguing that that reasoning is all the more reason Nevada shouldn’t have special permission.

At least five states have indicated they may try to legalize sports gambling if New Jersey wins its case, Brennan said.

In New Jersey, the Atlantic City casinos are watching even more closely. Revenue there is down 40 percent since 2006 and more than 12 percent just since last year, when Hurricane Sandy battered the shore.

Brennan said in an interview that the leagues are relying on an illogical argument. Sports gambling is already taking place everywhere, he said, so why not bring integrity to it by bringing it under the oversight of state regulators?

“Americans do not have a problem finding ways to bet on sports,” he said. “Either the leagues are willfully blind or they’re just incredibly ignorant when it comes to sports betting.”

Brian McCarthy, a spokesman for the NFL, said the league understands that people gamble on games. But legalizing it in more places would make people gamble even more, and the potential benefit of more interest in the games is outweighed by the risk to the integrity of sports, he said.

“Our fans, players, coaches, business partners all want to know that what is being presented on the field is real,” he said. “They don’t want to have to wonder whether a player missed a field goal or pretended he was hurt because he was throwing the game.”