With the federal government shutdown well into its second week, the patterns of what functions remain in operation are becoming clear, even though the reasons behind them may not be.

FBI agents and TSA security screeners are on the job, but park rangers are not. Social Security checks are going out, but military death benefits were withheld, until a private charity stepped in.

There is no federal law that automatically determines what stays and what goes during a shutdown. In general, government operations cease because the money runs out when Congress has failed to pass a budget by the start of the fiscal year on Oct. 1. So what explains the exceptions?

The answer begins with the Constitution. It provides that "no money shall be drawn from the Treasury but in consequence of appropriations made by law." In other words, no government agency can spend federal money without permission.

Congress went further in 1870 by passing a law, revised repeatedly since, that prevents the government from incurring debts or agreeing to pay money before it's appropriated. Known as the Anti-Deficiency Act, it has its roots in the spending habits of the executive branch in the early days of the Republic.

Government agencies, especially the military, would enter into contracts without already having the money to honor them. Congress, put on the spot, would appropriate the needed funds out of a sense of obligation to keep the nation's commitments. Fed up with the tactic, it passed the act in the wake of the Civil War.

As applied to the current shutdown, the law means that federal personnel can't be called into work, because that would incur a debt. But the law provides an exception for "emergencies involving the safety of human life or the protection of property."

So the key to determining who works and who doesn't in a shutdown is deciding which failures to perform government functions would constitute an emergency.

The current version of the Anti-Deficiency Act provides the answer: the law does not authorize "the ongoing, regular functions of government, the suspension of which would not imminently threaten the safety of human life or the protection of property."

The Department of Homeland Security, for example, has determined that keeping the Coast Guard on the job meets the terms of the law, but operating the e-verify system for determining the citizenship of a job applicant does not.

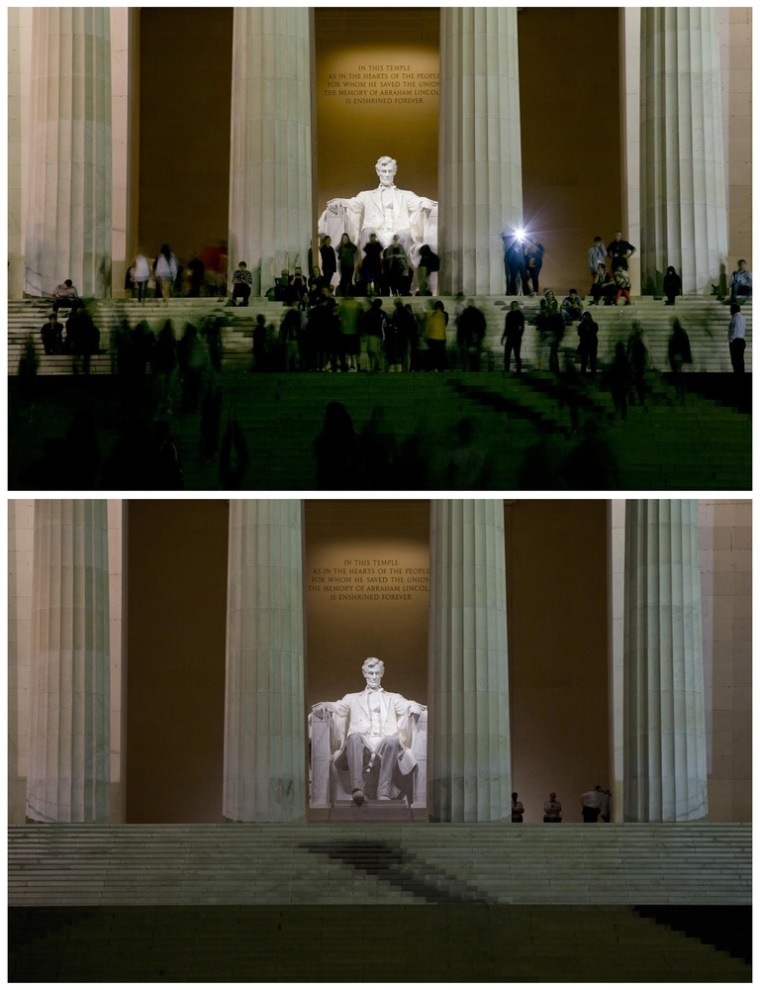

The same reasoning applies to national parks. Keeping them open, the Department of Interior has concluded, is not essential to safeguarding human life or protecting property.

Some decisions by government agencies are easy, some not so much. It's obvious why air traffic controllers and meat inspectors stay on the job. But administration officials say it was a closer call when they decided that the National Instant Criminal Background Check system, or NICS, would remain up and running, allowing the private purchase of firearms to continue during the shutdown.

The FBI's own website on the system provides the apparent answer, describing NICS as "all about saving lives and protecting people from harm -- by not letting guns and explosives fall into the wrong hands."

Social Security and Medicare benefits keep going for another reason: they're not paid from annual appropriations by Congress, so the legal authority to send those checks doesn't expire at the end of a fiscal year. The Justice Department has determined that the federal employees responsible for printing and mailing the checks can stay on the job, too.

The Anti-Deficiency law is silent on whether employees who continue to work in emergencies must be paid, though Congress has acted to do so during past shutdowns. On Sept. 30, the day before the anticipated shutdown, Congress passed the Pay Our Military Act, providing that military personnel would get their checks on time.

The Obama administration interpreted the law to allow the payment as well of civilian Defense Department employees "whose responsibilities contribute to the morale, well-being, capabilities, and readiness of service members."

That law did not, however, explicitly provide for the payment of death benefits. An administration official said lawyers at both the Defense and Justice Departments concluded that its meaning could not be stretched to authorize them, either.

A Defense Department official, Comptroller Robert Hale, warned on Sept. 27 that if Congress failed to pass a budget, "We would also be required to do some other bad things to our people ... We couldn't immediately pay death gratuities to those who die on active duty during the lapse."

The action by Congress on Thursday to fix that consequence of a shutdown, the "Honoring the Families of Fallen Soldiers Act" was actually an appropriations bill, funding a tiny but symbolically important slice of the entire Defense Department budget.

It passed the House by a vote of 425 to 0. But the Senate, refusing to pass any piecemeal funding bills, declined to act on it. A private charity came to the rescue.

"The Fisher House Foundation will provide the families of the fallen with the benefits they so richly deserve," said Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel.