When the Supreme Court agreed to take a case on prayer at government meetings, some advocates on both sides hoped for a clear resolution — a test that would establish, once and for all, what is acceptable under the Constitution.

They appear unlikely to get it.

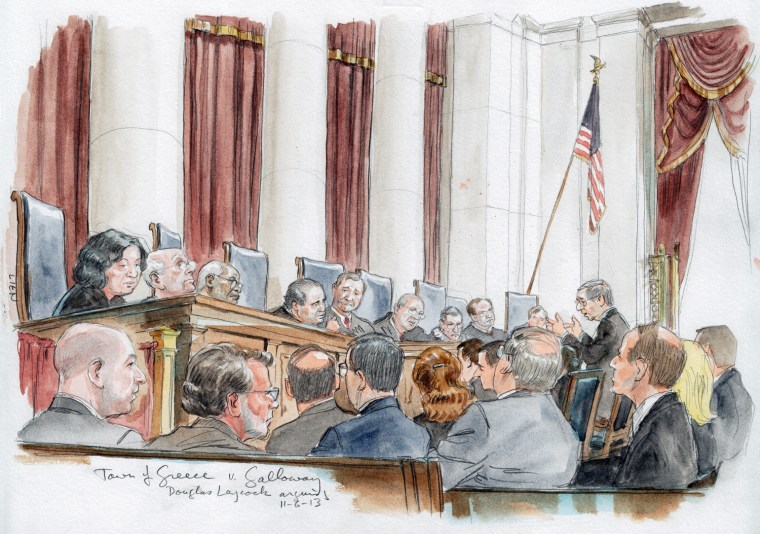

Arguments before the court on Wednesday, in a case from a small town in upstate New York, illustrated how thorny the issue isand how elusive a definitive answer will likely be for the justices.

Two women, one Jewish and one atheist, sued the town of Greece, arguing that prayers offered at the start of meetings of the town board amounted to coercion, and government endorsement of a single faith. The prayers were overwhelmingly Christian.

The town argues that the prayers are acceptable under a U.S. Supreme Court decision, which found that the Nebraska Legislature could open its sessions with a prayer from a Presbyterian minister acting as the state-paid chaplain.

It seemed certain during the arguments Wednesday that the justices had no interest in eliminating prayer altogether at government meetings. Beyond that, they grasped for solutions but mostly came up with questions.

For example: Does it matter if the prayer in question opens a legislative meeting, as opposed to a court hearing? Is it possible to craft a prayer that appeals to believers of all faiths, including, as Justice Samuel Alito said, Wiccans and Baha’i?

What about nonbelievers? Should the chaplain be given instructions to be inclusive? Who should write the prayers? And is any of this even the court’s, or the government’s, business to decide?

Justice Antonin Scalia wondered, to laughter in the courtroom: “What about devil-worshippers?”

“This one is hard,” said Amy Howe, editor and reporter for Scotusblog, a respected blog that covers the Supreme Court. “There really was a sense that the justices weren’t quite sure what to do.”

The town has history on its side. Prayers to open legislative meetings have been around since the Continental Congress — “part of the fabric of our society,” as Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote in the Nebraska case in 1983.

But Justice Anthony Kennedy, often the court’s decisive vote, did not appear fully satisfied with that.

“The essence of the argument is we’ve always done it this way,” he told a lawyer for the town, Thomas Hungar. “Which has some — some force to it. But it seems to me that your argument begins and ends there.”

At the start of the arguments, Justice Elena Kagan asked whether it would be permissible for the Supreme Court to open its sessions by having a minister face the lawyers and “acknowledge the saving sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross.”

Suppose, the justice said, “the members of the court who had stood responded, ‘Amen,’ made the sign of the cross, and the chief justice then called your case. Would that be permissible?”

Hungar, the lawyer for the town, said he didn’t think so. But in the case of prayer before a legislative body, court doctrine has found that the country, “from its very foundations and founding,” allows it, he said.

That was the essence of the 1983 decision. The women say their case is different. In Greece, they say, the opening prayer amounts to coercion because members of the public are often required to appear before the board for town business.

“It is impossible not to participate without attracting attention to yourself,” Douglas Laycock, a lawyer for the two women, told the justices.

“And moments later you stand up to ask for a group home for your Down syndrome child or for continued use of the public access channel or whatever your petition is, having just, so far as you can tell, irritated the people that you were trying to persuade.”

Chaplains in the town of Greece, the women said, have spoken of “our Christian faith” and of “us as Christian people.” An Easter prayer at a town meeting referred to spring as a symbol of “the new life of the risen Christ,” they said.

Organizations on the political right, plus 119 mostly Republican members of the House and Senate, saw the case as a chance for the Supreme Court to clarify a confusing series of rulings on the line between church and state.

They asked the court to adopt a simple, more permissive test — requiring only that the government not force participation in any religion or religious exercise, or create a national religion.

The American Civil Liberties Union, which filed a brief in support of the two women, wanted the court to overturn the 1983 decision allowing prayer to open sessions of the Nebraska Legislature.

“The court should close this constitutional loophole and keep the government out of the religion business,” Daniel Mach, director of the ACLU’s Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief, said in a statement after the arguments.

One plausible outcome, Howe said, would be for the justices to allow the town of Greece to continue its practice. The justices could tell the lower court that it decided the case wrongly, and that all that needs to be examined is whether the prayer proselytizes for or denounces any particular religion, the standards of the 1983 case.

Or, as Justice Stephen Breyer suggested, the justices could instruct the town to be more inclusive in whom it chooses to offer the prayers, and to give chaplains clearer guidelines, Howe said.

“The court’s going to have to draw the line,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California, Irvine, who filed a brief in support of the two women.

“Both sides agree that’s there a line in terms of when prayer becomes impermissible,” he said. “The question is where does that line get drawn.”

Related:

Supreme Court tests limits of prayer at official government meetings