This was originally published by the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting.

Editor's note: The following account is based on dozens of police reports, court documents and testimony spanning nearly 20 years. The details and events described throughout this article, including recollections of specific situations, are derived from these records.

Dig deeper

Avelino Tamala's green Ford Bronco cut through the crisp desert night, headlights revealing glimpses of scattered creosote bushes along the shoulders of State Route 238. He knew the sparsely traveled highway southwest of Phoenix from his days as a patrol deputy with the Maricopa County Sheriff's Office, before he became a detective.

Tamala still carried a gun, but no longer wore the badge — he abandoned that two years earlier for a romance with one of his confidential informants, Anna Reyes, the woman in the passenger seat that night.

His knowledge of law enforcement and her connections to Mexican drug cartels now afforded the couple a lucrative career selling drugs smuggled into the United States. The green Bronco provided an ideal transport for bundles of marijuana.

But that night the cargo in the trunk was much lighter, and to them, seemingly less valuable: Reyes' 3-year-old daughter lay lifeless behind them, wrapped in a white bed sheet, a shovel next to her tiny body for what would follow.

The Bronco slowed as they passed milepost 26. Tamala maneuvered the vehicle about a mile along an unpaved passage intersecting the highway, surrounded by little more than flat, undeveloped desert.

Opening the back hatch, Tamala removed the shovel and clutched its red handle. He drove the blade into the earth.

Reyes watched Tamala dig, holding a flashlight as she illuminated the unmarked grave. She broke the silence to utter two final words before they placed her daughter into the earth:

"Dig deeper."

Crystal Reyes, the 3-year-old girl buried that cold April evening in 1997, would have turned 23 this year. Her short life, marred by abuse at the hands of those who were supposed to care for her, is a brief chapter in a tangled narrative of crime and love, deceit and heartbreak.

Hers is a case that stirred, for years, in the minds of those who investigated it, the details cemented in their memory after the initial investigation went cold, after it stagnated for more than a decade, after it was reopened in 2013 — still today as the investigation continues nearly 20 years later.

'Whispered Secrets'

In 1991, Darren Stockwell worked as a detention officer at the Maricopa County Durango Jail. He was 23, and one of his responsibilities was to oversee the hour of outdoor recreation allowed each day to inmates, including Anna Reyes, then 25 and serving a three year sentence for trafficking marijuana.

Reyes had thick, black hair, brown eyes and full lips that hid her perfect teeth.

"She was an attractive lady," Stockwell said years later in court.

Official records, deposition transcripts and court proceedings described Reyes as a woman who wielded her beauty to manipulate the men around her.

She took a special liking to Stockwell, a tall, good looking man with a light complexion and muscular build. The two played games of HORSE on the basketball court at the county jail, just the two of them because, for safety reasons, Reyes was separated from other inmates.

Flirtation made its way into their brief interactions. Yet beyond the amorous poem "Whispered Secrets" that Reyes had passed along to Stockwell, they avoided crossing boundaries. The flirtations had to stay just that.

Reyes was granted parole on March 26, 1992, just four days before her 26th birthday.

"It wasn't too long after she was released, I got a call at the jail," Stockwell said. "It was Anna."

The purpose of the call came as no surprise — Reyes wanted to meet up, but jail policy bound Stockwell to wait a year before interacting with former inmates.

They spared no time after the year had passed. For several months, they spent nearly every day together.

"Yeah, I fell in love," Stockwell said during trial testimony. "I was young and dumb, but I did."

They discussed moving in together, which made even more sense to Stockwell the day Reyes came to his apartment with news.

"I was overwhelmed, but sort of happy. I wanted us to get together," he said. "She was pregnant — I wanted to do it right."

Reyes had other plans.

She was still legally married to another man with whom she had three children, and her parole dictated that she live in a stable home. Stockwell said Reyes told him she wanted to have sex with her husband one last time, to mislead him into thinking the pregnancy was his, divorce him and then request money for child support.

"I was devastated," Stockwell said. "So I walked away."

Unwanted

Crystal was born Nov. 26, 1993, at a clinic in Nogales, Mexico — where her mother grew up, where her grandmother still lived.

Within days, Reyes brought her newborn daughter back to the U.S. and immediately tried to give Crystal away.

Reyes' longtime friends Sergio Cazares and his girlfriend Mayda Diaz were interested. They knew Reyes from Nogales, but had since moved to Tempe.

Mayda, barely able to speak in court as she fought back tears recalling the interaction, said she thought Reyes was joking when "she asked if I wanted her."

"Of course, she's beautiful," Mayda replied.

Mayda and Cazares had many children already, but they agreed to take Crystal as long as Reyes followed through on making the adoption official. They kept Crystal for about a week, and by then Reyes hadn't taken action on the adoption paperwork, so the couple gave the girl back to her mother, thinking Reyes simply didn't want to raise an infant.

"I knew she would eventually try to take her back," Cazares said. "That's why I wanted the (adoption) papers."

Reyes took Crystal to Mexico, where she would live with Reyes' mother.

Reyes returned to Arizona in December 1993, but less than a year later, she was sent back to jail for violating her parole. Records detailing her violation have since been purged.

Reyes wanted a way out. She called on her friend Cazares, who was working as a confidential informant for a narcotics detective at the MCSO Special Investigation's Division.

The detective's name was Avelino Tamala.

A detective and his informant

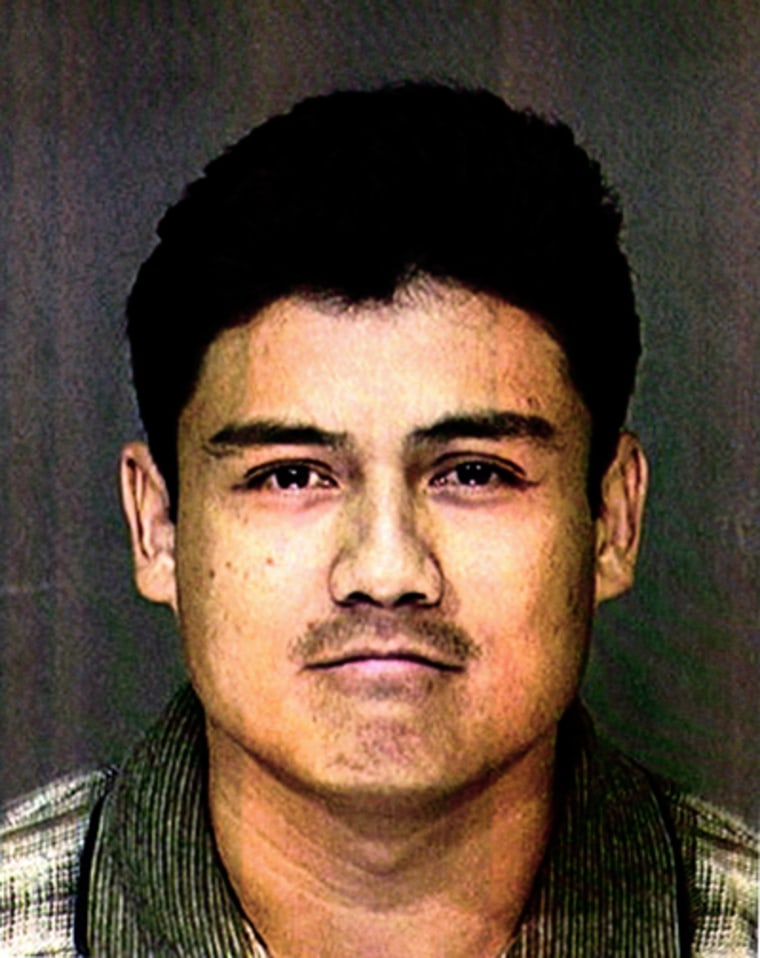

Avelino Tamala began his law enforcement career as a transportation officer with the Maricopa County Sheriff's Office in 1985, when he was 22. Most people called him "Al."

He moved up quickly within MCSO, working first as a detention officer, then patrol officer. By 1990, he had risen to the rank of detective within the agency's narcotics division.

Tamala's superiors considered him a hard-working, effective lawman who kept to himself and produced results.

"He was the guy doing it all," said Sgt. Richard Rosky, Tamala's then-lieutenant. "He was one of my best detectives at the time."

Cazares told Tamala about his friend, Anna Reyes, who was in jail but wanted to cooperate with law enforcement in exchange for a reduction to her sentence or charges. Tamala met with Reyes in 1993, and she told him about her family — the Somozas — and their heavy involvement in the Mexican drug trade.

Darren Stockwell said years later that he remembered seeing Tamala visit Reyes in jail in 1991, but MCSO supervisors said they weren't aware of any visits. Investigators acknowledged there were conflicting accounts regarding when Tamala and Reyes first met.

Still, the information Reyes gave Tamala in 1993 resulted in arrests and sizable drug seizures, which proved to Tamala's superiors that Reyes might be more useful out of custody.

Capt. Steve Werner led the Special Investigations Division at the time and oversaw Reyes' release from jail. Their agreement stipulated that Reyes would work as an informant for MCSO, as well as several local, state and federal agencies.

MCSO records detail Werner's arrangement, which addressed one notable characteristic of Reyes that he thought could lead to problems.

"Werner said that [Reyes] had a reputation of becoming sexually involved with officers and that she was considered by many to be very attractive," records state. "To avoid problems of this nature Werner ordered that two officers be assigned to [Reyes] at all times."

A second detective, Gary Eggert, was assigned to work with Reyes and Tamala. But Eggert quickly became frustrated by the arrangement, because most of the tips Reyes provided fell flat.

One of those instances took place in October 1994, after Reyes told detectives about a sale of 200 pounds of marijuana. They arranged an undercover deal and made an arrest, but the drugs they seized came in 140 pounds light. Reyes later told Tamala she had "skimmed" the load and sold the rest herself. At the time, the payout would have been worth tens of thousands of dollars.

"Everybody in the office, I think, was expecting some, you know, us to bring down the Colombians or something," Eggert said at the time. "And it just wasn't happening."

The results were warning signs to Eggert. He started noticing Reyes and Tamala were becoming close.

"I just kind of felt uncomfortable about the situation and I didn't ... if something happened bad, I didn't want to be a part of it," Eggert said. "You have a sixth sense that hey, you know, stay clear of something. And this could be something bad."

Eggert went to Rosky, Tamala's then-lieutenant, asking to be reassigned and told him about Tamala's slipping performance and closeness with Reyes.

Rosky questioned Tamala about Reyes, but Tamala assured him nothing was happening between them. Other co-workers eventually started speculating about Tamala's relationship with his informant. It became an "office joke," according to records.

In 1995, the sheriff's office opened an internal affairs investigation. The resulting report accused Tamala of "fraternizing" with Reyes.

Tamala admitted to investigators that since September 1994, just months after Reyes became an informant, he'd been periodically living with her.

Werner, the investigation's division captain, brought Tamala into his office and gave him a direct order to end the relationship. Tamala refused, so Werner asked for his badge and resignation.

In a subsequent letter to the Arizona Peace Officer Standards and Training Board advocating that Tamala never again be hired into law enforcement, Werner wrote, "The tragedy of this affair lies in the fact of his blatant, uncaring attitude and lack of remorse which was displayed to Sergeant Rosky and myself at the time when I accepted his resignation."

An office secretary, Rosanna Galindo, lamented Tamala's downward spiral, telling internal affairs investigators, "I just think it's kind of sad what happened to him, because he's a real nice guy. And I don't know, you know, what's going to happen to him.

"I guess love can make you do anything."

Shadow Rock

Although Tamala had walked away from his career and income, his relationship with Reyes brought a job prospect far more lucrative than the salary of a detective.

By August 1995, Tamala and Reyes started selling smuggled marijuana. Tamala logged their transactions — worth hundreds of thousands of dollars — in a ledger he kept in a storage locker.

The couple could now afford to rent a two-story, five-bedroom house in a gated Ahwatukee community. It had a pool, and the backyard abutted a small mountain called Shadow Rock. The rent was $3,000 a month.

The home had plenty of space for Reyes' three adolescent children — Juliana, Thalia and Luis — who had lived with Reyes since her most recent release from jail. Reyes hired a live-in housekeeper to clean and care for the children while she and Tamala were away on trips to Mexico, Nevada or elsewhere in Arizona.

The 21-year-old housekeeper, Maria Gutierrez-Diaz, had recently moved to Arizona from Sinaloa, Mexico, and knew very little about America. It was easy for Tamala and Reyes to convince her that Tamala was still an undercover detective.

Reyes' niece, Annette Rodriguez, believed the same when she moved to the home in September 1996. She was a sophomore in high school and had been going through a rough patch with her mother. She wanted to finish high school while living with her aunt.

Nearly 20 years later, Diaz and Rodriguez would testify in court that they thought Tamala and Reyes, the three children and the big house in a wealthy Phoenix suburb indicated a stable family, normalcy.

They didn't know about the double life Tamala and Reyes were living. The illusion of a suburban household evaporated when Reyes' youngest daughter, Crystal, came to live with them.

Crystal

Crystal had just turned 3 when her grandmother brought her back from Mexico to live in the U.S. with Reyes and Tamala in November 1996.

Crystal appeared happy, smiling often, Diaz said. She had a light complexion, amber hair in ringlets and blue eyes — traits from her father. She seldom talked. When she did, she only spoke Spanish.

"She was a beautiful girl," Diaz recalled years later. "Very, very pretty little girl."

Rodriguez thought the same, as did most who had met Crystal.

But Rodriguez and Diaz thought it was strange that Crystal ate alone at the dinner table, only after everyone else had finished. Stranger still, without a bed of her own, the child slept in a closet, just sheets and pillows laid out on the floor.

Diaz told police that Reyes once hauled the child into a bathroom after she heard Crystal bragging about being prettier than her sisters. Tamala and Reyes used a pair of hair clippers to shave off her curls, laughing as they did it. The other children joined in, Diaz remembered.

"Maybe they thought it was a joke or game," Diaz said. "But it seemed weird to me that someone would do that to a little girl."

For Christmas that year, Reyes and Tamala rented a condominium in Colorado for a family skiing trip.

During a snowball fight between cousins, Tamala and Reyes brought Crystal outside to join. She was barefoot and wore nothing but pajamas, Rodriguez later testified in court. The other children started throwing snowballs at Crystal. So did Reyes and Tamala.

Rodriguez eventually went inside to shower and change. She then heard Tamala and Reyes yelling at each other. They were in another bathroom, with Crystal under a hot shower — her skin blue, her body shaking uncontrollably.

Reyes and Tamala were arguing because they thought Crystal was going to die, Rodriguez said. The shower revived her.

Several weeks after the Colorado trip, Rodriguez decided to move back home with her mother. She was scared of living in the Ahwatukee house — scared of Tamala and Reyes. She didn't see the abuse escalate.

Diaz, the housekeeper, did.

"It was awful," Diaz said.

Tamala and Reyes started binding Crystal's hands and feet, sometimes from one doorknob to another in the small utility room that provided access to the garage. Abrasions formed around the child's wrists and ankles.

Her cries would go ignored by the family and, Diaz said, Tamala once stepped on the child, still bound, as he passed by.

Crystal was soon confined to a small plastic dog crate, the inside just 20 inches wide. Sores began to develop on her body because she couldn't move away from the excrement and urine that soiled the floor. The crate was too small for Crystal to fit comfortably, forcing her to live in a perpetual bent position. Dark green bruises spotted her frail arms.

Sometimes, Reyes and Tamala took Crystal and the kennel to the backyard so they could hose her down. They would spray the inside of the kennel, too, before putting the girl back inside to lie on the hard surface without a blanket or pillow.

Crystal's cries, muffled slightly by the confines of the crate, soon turned to whimpers. They became softer as hours of captivity turned to days, then weeks.

She stopped eating and, eventually, stopped urinating and defecating, Diaz recalled. Crystal's once-plump body had withered, her skin now clinging to her tiny bones.

She began to starve.

'Bury her'

One chilly afternoon in April 1997, the sun began to take cover behind South Mountain, casting a shadow over the Ahwatukee Foothills neighborhood where Tamala and Reyes lived.

That evening marked the final act of Crystal's abuse, detailed to investigators years later during an interview with Tamala. His words would become the only account of Crystal's death.

As the sun began to set and the three older children played in the driveway, Tamala and Reyes retrieved their bicycles for an evening ride.

From her kennel inside the garage, wearing nothing but a pair of underwear, Crystal called out to her siblings.

"Cállate," Reyes yelled in Spanish as she pulled the child from the kennel.

According to Tamala, Reyes placed a bath towel over the girl's head, then used clear packing tape to wrap her up, securing the towel around her face and binding Crystal's arms to her sides.

"Don't do this," Crystal pleaded, promising that she'd be quiet. But Tamala said Reyes then placed the starving child — bound and gagged — into a tall cardboard box.

With Crystal silenced, Tamala and Reyes left the children at home while they rode their bikes for more than an hour.

It was dark when they returned. Reyes went into the house. Tamala went straight to the box in the garage. Crystal was still standing, though slumped against one side.

He frantically pulled her out, Tamala later told investigators, ripping away the tape and unwrapping the towel. The girl's arms and legs had turned blue — her eyes wide open even though she was already dead.

"There's something wrong," Tamala told Reyes after running inside to usher her downstairs and into the garage.

Once there, Tamala said he knelt beside Crystal's body to revive her. Several minutes passed before he stopped the chest compressions, giving up.

"There's nothing else I can do for her," Tamala said. Reyes stared, expressionless, and told him to keep going.

"No, she's alive," Reyes said. "She's alive."

Tamala said they argued over whether to call 911, but Reyes didn't want police and paramedics to come.

"Bury her," Reyes said in Spanish.

An investigation opens

By the summer of 1998, the once-cozy life for Tamala and Reyes was unraveling. The couple left the Ahwatukee home in June for Tucson, but after a short time, Tamala moved in with his mother in Phoenix.

Reyes, along with her three other children, moved to Tempe with her friend Sergio Cazares, the informant who worked with Tamala in 1993.

Cazares and his girlfriend, Mayda Diaz, having met Crystal just weeks after she was born, asked about the little girl. Reyes lied. She told them Crystal was living in Mexico.

Reyes and her children moved out a few weeks later. But shortly after that, Tamala came looking for them. Cazares asked him about Crystal.

"From what I understood, he told me that she was no longer alive," Cazares said, adding that Tamala told him Crystal's body was in the desert — that it couldn't be found.

"If there's no body, there's no death," Tamala told him.

Cazares told a detective with the Maricopa County Sheriff's Office. That information was given to Phoenix Police Department Detective Don White, who was assisting several federal agencies in an ongoing narcotics investigation into Tamala and Reyes.

White, along with the lead investigator in the federal drug case, Special Agent Joe Slatalla of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, had been close to securing indictments for Tamala and Reyes.

The possible homicide case was handed off to another Phoenix Police detective, Michael Meislish, in February 1999.

Meislish said his investigation was "somewhat unusual" compared to other homicides he had worked. For the first several months, he relied on secondhand, after-the-fact information brought to him from detectives on the federal drug case.

"I was kind of secondary to what was going on in the other investigation," Meislish recalled during Tamala's trial.

His first hands-on work in the case came Dec. 16, 1999, two days after federal investigators interviewed Tamala under an agreement that protected him against prosecution for anything said during the interview. Tamala told federal investigators, in explicit detail, about Crystal's life at the home in Ahwatukee, her death and the night he and Reyes buried her in the desert.

Meislish and a group of other officers and detectives went to the site Tamala described. They came up empty-handed.

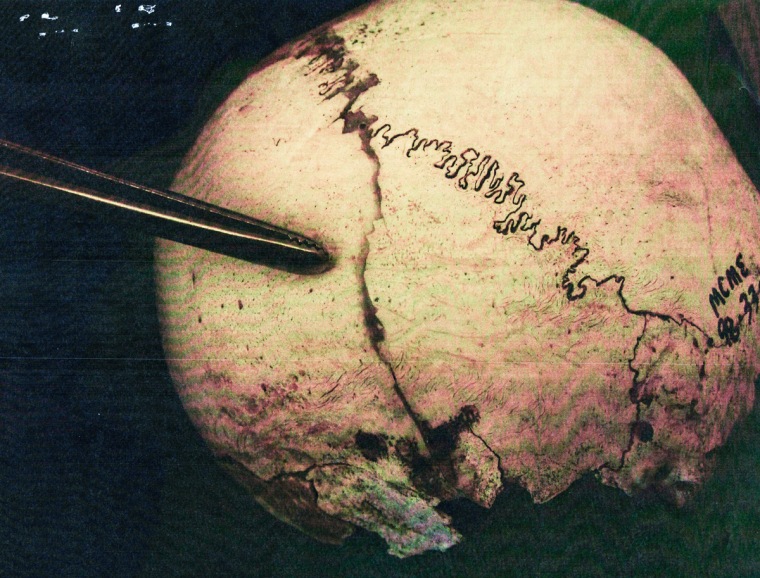

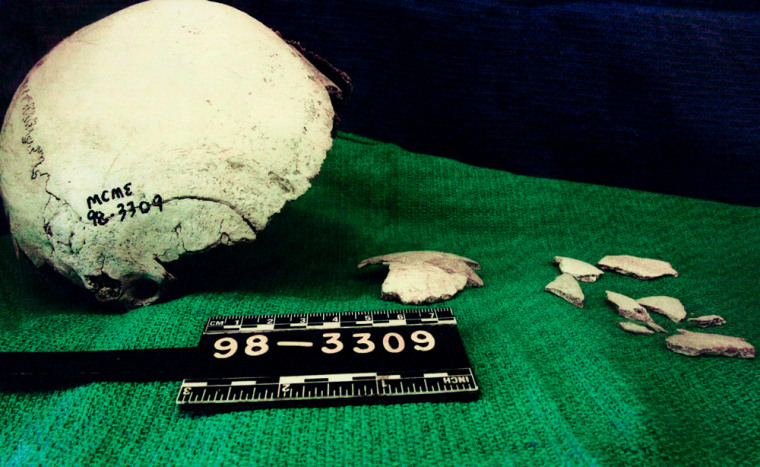

But a call in January 2000 to the Maricopa County Medical Examiner's Office revealed that fragments of an unknown child's cranium were found more than a year earlier.

In November 1998, 19 months after Crystal was buried, a quail hunter stumbled across what he suspected were pieces of human bone. He contacted police, who confirmed the fragments were human remains, but investigators didn't have any leads, and they didn't yet know of Crystal's death.

By the time Meislish linked those fragments to Crystal, Tamala and Reyes had been indicted on federal crimes for conspiring to distribute and possess, with intent to distribute a controlled substance, making it easy for him to obtain a sample of Reyes' DNA.

Without the father's DNA, however, the bones couldn't be positively identified as Crystal's.

To bring charges against Reyes and Tamala, Meislish needed to prove that fact. He knew about Crystal's abuse, but only through interviews protected under the federal agreement with Tamala.

Meislish tried to contact Maria Gutierrez-Diaz, the housekeeper who lived with the family in Ahwatukee, but he couldn't find her. Official records didn't detail why the biological father, Darren Stockwell, wasn't contacted or asked to provide DNA.

The case went cold.

Once silent

ATF Special Agent Joseph Slatalla, the former lead agent who helped convict Tamala and Reyes on drug charges, was about to retire. He knew about Crystal's murder — that the investigation into her death had gone dormant — and contacted cold case Detective Dennis Olson with the Maricopa County Attorney's Office in 2013.

Olson agreed to revisit the case and started reading through dozens of police and investigative reports about Crystal's murder. He learned that no one ever talked with Diaz.

New advances in law enforcement databases made it easier for Olson to find Diaz, who was living at her sister's home in Phoenix.

Olson and a Spanish-speaking detective spoke with Diaz at her sister's home that year. It was the first time Diaz had talked with law enforcement officials about the case. But after a brief conversation, Diaz told the detectives that she hadn't witnessed Crystal's abuse.

Again, the case stalled.

A year passed before Diaz called the detectives.

"(Diaz) requested to speak with me about what happened to Crystal, because it was time for the truth to be known," Olson stated in his report about the call.

Diaz told Olson about what she saw at the Ahwatukee home, explaining first why she didn't tell him the full story when they first met: She was afraid of speaking up — afraid of Tamala and Reyes. She thought the couple may have had something to do with an incident that hospitalized Diaz for several weeks in April 1997 — the same timeframe that Crystal was believed to have been murdered.

Diaz recounted that evening on April 12, 1997, when Reyes dropped her off at a nightclub, on her weekend off, to meet her then-boyfriend and her sister. After a night of dancing, they left the club to find the window of her boyfriend's vehicle shattered. Nothing was missing from the car.

While driving home, a car pulled up next to them. The people inside had guns.

"They started shooting and everything happened so fast. I bent down but they had already hit me," Diaz later recalled at Tamala's trial, barely able to speak through her tears. "I didn't realize at that moment that (my boyfriend) was dead."

Diaz was shot in the neck and spent two weeks recovering in the hospital. She returned to the Ahwatukee home to continue working for Reyes and Tamala.

Crystal wasn't there.

After several weeks, Diaz quit. She said "it didn't feel right being there." She moved in with her sister.

More than 15 years after her boyfriend was killed, after she was shot in the neck, after she moved in with her sister, Diaz told Detective Olson her full story. She detailed the abuse in Ahwatukee. She told detectives about the time Tamala visited her sister's home, after she had quit, subtly telling Diaz that her shooting wasn't random, warning her about Reyes.

Diaz also told Olson, again recalling the details in court, that she thought she recognized one of the gunmen from April 1997. She thought it was the same man who Reyes had talked to shortly before the shooting, when she and Reyes stopped at a grocery store, when Reyes got out of the car and talked to the man while pointing at Diaz, when she and Reyes left the store without ever going inside.

Diaz told detectives that she didn't think going to the police sooner about Crystal's abuse was an option. She thought Tamala was the police.

A father and his DNA

With a witness to Crystal's abuse, Olson's renewed investigation into her murder had started to take shape. He continued tracking people down, including the man detectives believed was Crystal's biological father.

Darren Stockwell, the former MCSO detention officer whose relationship with Reyes ended several months after it began, was living in north Phoenix. It had been more than 20 years since he met Reyes. He hadn't heard from investigators about the case since shortly after a detective left a business card on his front door in 1998.

On Aug. 1, 2014, Olson visited Stockwell at his home.

Stockwell was surprised to see the detective. He was "in shock" when Olson told him about bone fragments found in the desert, that the remains were likely his daughter's, he recalled in court.

Stockwell couldn't be certain that Reyes was telling the truth about her pregnancy in 1993. He didn't know that he actually had a child, let alone that she was dead.

Olson asked Stockwell if he was willing to provide a sample of his DNA, to prove the bones were Crystal's. He initially refused, but provided a sample when Olson returned with a warrant.

"I didn't know what to think, I was overwhelmed," Stockwell said. "It was pretty earth-shattering news."

In court, Olson described the emotional interaction with Stockwell, when his eyes filled with tears as he learned he did have a daughter, that she was dead. His eyes welled again when he saw an old photo of Anna Reyes.

But Stockwell also had questions, Olson said, adding that, before the DNA test, "Stockwell asked why he wasn't contacted at the beginning of the investigation in [1998]."

Olson simply told him, "I don't know."

The DNA analysis, combined with Tamala's interviews and Diaz's statements, was enough to indict Tamala and Reyes on murder charges in December 2014.

Tamala, who was on probation after serving 10 years in prison for the federal drug conviction, was arrested and booked into the Fourth Avenue Jail. His murder trial began on Oct. 18, 2016.

One verdict, one wanted

For a month, jurors listened to testimony. The group of detectives that investigated Crystal's case described their interviews, their successes and failures. The housekeeper wept as she recounted Crystal's abuse and the whimpers of a starving child. Forensic experts offered differing views about how Crystal died, agreeing only that there wasn't enough evidence to determine a specific cause of death. Friends, family and acquaintances detailed their encounters with Tamala and Reyes. Crystal's father talked about his romance with Reyes, how their abrupt breakup devastated him.

They all had stories to tell. Some contradicted others.

The truth of exactly how Crystal died was elusive. The 17 fragments of bone weren't enough to determine whether fractures in Crystal's partially recovered cranium suggested more to her death than a towel taped to her head.

But that's not what the jurors were instructed to decide. Their task was specific: Should they find Avelino Tamala guilty of murder?

It didn't take long for jurors to reach a verdict. The group moved into deliberations about 4 p.m. on a Monday. The notification that went out to legal counsels, asking them to return to court, came at 1:27 p.m. the following day.

It was Nov. 8, 2016. Election Day.

Seated in the front row, immediately behind prosecutors from the Maricopa County Attorney's Office, Darren Stockwell stood as the jurors entered the room. Behind him, nearly a dozen law enforcement detectives and retirees involved with the case waited.

Stockwell stared ahead as the verdict was read, exhaling as his shoulders fell.

Guilty.

One by one, the jurors exited and walked past Stockwell, some with nods and shallow smiles as they made eye contact with Crystal's father.

As Avelino Tamala awaits his sentencing on Dec. 9, the search continues for the woman at the center of a tangled web of lies and deceit, manipulation and murder.

Anna Reyes was deported to Mexico in 2008, after serving eight years of a 10-year prison sentence for the federal drug conviction. She was living in the U.S. illegally.

Her whereabouts are unknown.